It's All Good Man

Add “Wrote A Children’s Book With His Daughter” To Your Reasons To Love Bob Odenkirk

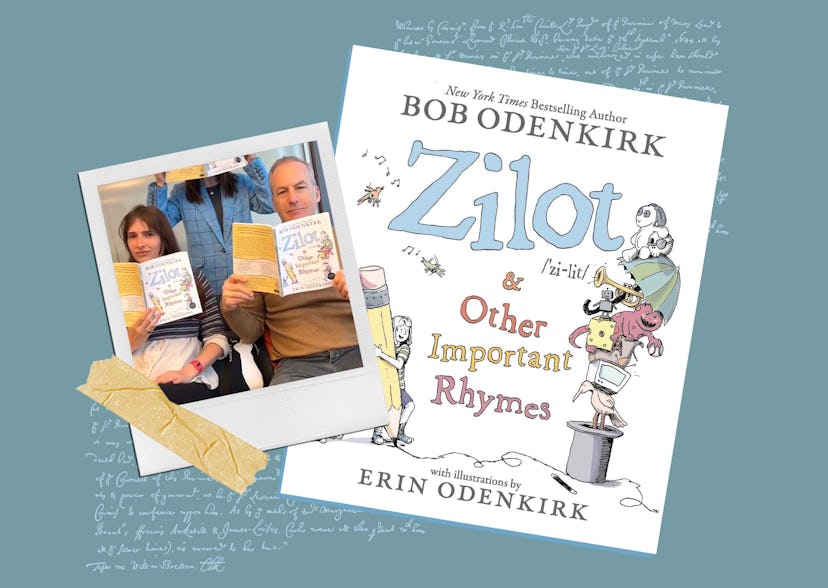

Zilot & Other Important Rhymes is a delightful (& perfectly silly) collaboration that’s been in the works since Bob Odenkirk’s kids were small.

An “awful good” (or “good awful?”) kid blithely recounts his day spent ruining a wedding. A sign advertising a sign maker is “order of out.” A cat named Larry dreams about his dearly departed pet mouse. Thusly the world of Zilot & Other Important Rhymes — Bob Odenkirk’s new book for children, illustrated by his daughter Erin — is populated, and thusly will bedtime reading routines be that much more delightful from now on.

Inspired by the poems Bob wrote for and with Erin and her brother Nate when they were small children, Zilot takes its title from a word Nate invented years ago. (Erin is now 22 and Nate 24.) One day, Bob explains, his little boy declared, “Let’s build a zilot!” Perplexed, his family asked what he was talking about. “A blanket with a couch and a chair!” came the reply — a blanket fort!

“He was like 6, so young enough that it just came out of his brain, but old enough that he was able to say the word and ask for it and talk about it,” says Bob. “We just thought it was a great word.”

Dedicated to Bob’s wife Naomi and to “all people who read to kids,” this collection of 80-plus poems, which truly comes to life thanks to Erin’s charming and distinct illustrations, is by turn nonsensical, funny, clever, and, on more than one occasion, gently existential. In “When I Grow Up,” the narrator considers a future career as a garbage truck, then a house, before settling on a raindrop: “I’ll be the water that waters the plants. I’ll live forever; I’ll never die. I’ll grow something new with every goodbye.”

Amid the silliness there are some quite profound words of encouragement and wisdom, which thankfully never bonk you over the head with a preachy message. “Put the lesson in the background, if you even have a lesson,” says Bob of his philosophy about what makes a good children’s book — and good art in general. “Let it be something that kind of rises up as you contemplate the piece. But let the action, let the humor, let the silliness, be in the foreground and be the entertaining part. That’s certainly true of movies and TV shows that I’ve been in, too. If you think you have something you need to tell people or explain about life or advise people with, that’s a sermon or a politician’s presentation, it’s not a piece of entertainment.”

Ultimately, Zilot is the best kind of children’s book — one that’s entertaining for the kid and for the person reading it out loud. Here, we chatted with Bob and Erin about their first joint venture (as a couple of grownups).

What was the best part of getting to work together?

Bob: I loved Erin’s drawings. Her drawings made me smile. They were beautiful, and she had a style almost immediately. She may disagree with that, but I felt she had grasp on a line choice and a style choice very quickly that she was carrying on through the different illustrations. And I thought that was a very professional presentation she was showing me.

“I’m a pretty silly guy, to be honest with you.”

Did you consider other illustrators?

Bob: No.

Erin: Not an option.

I have a college-age daughter myself so, tell me, what kinds of arguments did you have during the process?

Erin: If anything, they were mostly like teenage daughter talking to her father-type arguments. They weren’t so much about the content of the book or the direction of the book. They were just like, “Can you leave me alone?” type arguments. We don’t even argue that much. I think we had a pretty shared sense of where this book was going, and we both very much trusted each other to do our respective parts and didn’t bother each other too much and just kind of trusted that the other one was going to figure it out.

Bob: There was one point that was challenging, which was when we first put the book together. It was called Old Time Rhymes at that point, and we did not get a bite from a publishing house. One place wanted us to make it more aggressive and more wild and intense. And I think that was a real learning experience to sit and think about: what do we love about these poems? What are they about? They’re about language. They’re about encouraging kids to try things and not be afraid to fail. They’re about taking your time or being silly.

And so we refocused the book, did a little bit of rewriting, and built it around this word that my son had invented. It’s about being comfortable with language and having fun with expression and not being afraid to look silly. That was a tough moment, because Erin might’ve felt like, “Well, if we’re told no, we should just do what they say.” But we both took our time thinking about it and realized that it has a sweet nature. It was written with the kids when they were between 4 and 8. It is really built for little kids, by little kids.

So many children’s books these days have a really didactic empowerment message, or a “you must grow up and save the planet!” message. And there are some great philosophical moments in Zilot, but it’s also just really silly and sometimes poignant. How did you think about how you wanted the effect of the book to come across as a whole?

Bob: About 25 of these poems were written after the kids were grown up, but I had written most of the poems with a little kid by my side, sitting in my lap, where the kid would write a line or the kid would suggest the poem. And so [to write the new ones] I really needed to try to think back to what kids are thinking about and feeling and what’s in their day. The poems that I initially wrote when I did not have a kid were all didactical and lecture-y. And I just threw them out, because a kid doesn’t want to hear that. They want to be entertained and have fun, and if there’s a lesson buried in there, fine. In the end, it’s defined by those two kids, Nate and Erin, when they were 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, helping me to think about how they saw the world.

There are a couple poems in there that really reminded me of what it’s like to be a child and be in that space where you’re kind of open to this more whimsical logic. Erin, did you feel like you were more closely connected to that childlike space, or was your dad?

“When the kids would write a poem or help me write a poem, they would say a line that maybe didn’t make a lot of sense, but I would just write it in there and pretend it was great.”

Erin: I think he lives there all the time. I think I’m further removed from it!

As a person existing in the world, I care a lot about being taken seriously. I have a little bit of anxiety about it. I take everything seriously and everyone seriously, and I kind of expect the same. And I think that’s why I have so much joy in breaking that as well. But he definitely, through my whole childhood and now even, lives in that head space. He’s a serious person on the outside. But—

[Bob makes a Very Serious expression.]

Look at that serious face.

Erin [not blinking]: I think when you throw an audience in front of him, or you throw a kid in front of him or a dog in front of him, or when he’s being quiet by himself, you can safely assume there’s something silly happening in his head.

Bob: I’m a pretty silly guy, to be honest with you. Most of my career I wrote sketch comedy. And in working on these, I did feel almost immediately like, “Wow, these are little sketches.” These are little comedy sketches. They have an idea and it’s a twist usually. And then you play with it a little bit, and then you find a way out that takes it to another level. It’s very similar to writing sketches, which I did for Saturday Night Live and Mr. Show and many other shows.

How did you find writing for an audience of children compared to writing for grownups?

Bob: Well, I think that kids have a high tolerance for absurdity. One of the things I would tell parents if they try to do what I did, which is: when you’re doing reading time, take out a notebook or just a loose notepad and write a poem with your kids. But what you have to do is you have to let it be pretty absurdist, because kids want to rhyme. It doesn’t have to make sense so much. And they’re proud of it. You should let them be proud of it. When the kids would write a poem or help me write a poem, they would say a line that maybe didn’t make a lot of sense, but I would just write it in there and pretend it was great, and make them feel good about having written a poem.

Erin: And sometimes it was great! Sometimes that ability to access absurdity — you lose it as you get older. It was kind of a treasure trove of absurdity that we got to reopen to write this book, and we found it difficult to re-access that part of ourselves in writing the new fresh poems.

Some of the poems kind of give the kid the sense that they’re in on the joke first — ahead of the narrator, or ahead of the person who’s reading it. I’d forgotten what a fun experience that is, as a child. Is that something that you thought about deliberately?

Erin: Totally.

Bob: I think that goes to sketch comedy too. One of the things young sketch writers often do is kind of bury the joke and you can’t find it for two pages. And it’s like, no, no, no. Put the joke up front. Let me know how it’s funny right away. And then let me enjoy the ways in which you have fun with that. So yeah, it’s very related to the work I did all my life.

Erin, what’s the best advice your dad has ever given you?

Erin: It’s a little complicated, because there’s never one succinct phrase he held onto. But I think piecing together a few of his things, I learned from him that anything starts somewhere and it’s probably somewhere bad. And doing it every day, no matter what it looked like yesterday, or the confidence you have about it today, is the only way to get there. Just sit down and do a little bit of it today and tomorrow and the next day. That sort of commitment to yourself and to the work is what grows good work. And that could be for anything, that could be for art, that could be for going on runs and working out; that could be for meditation or checking in on your friends, whatever the goal is, try a little bit every day.

Bob: Incrementalism.

And Bob, do you have any words of wisdom or parenting advice that you pass on to people with little kids?

Bob: Oh, advice to parents is if your kid’s upset and crying, it’s probably because they’re tired, not because they actually need food or need anything. They just are tired. Kids are tired a lot until they’re like 7.

I also think what we did here is pretty special. And I’d say other parents who think it’s cool should do it! Get a notebook and when you read, do your reading, and then write a poem about the day or something that happened or something silly, just the silliest thing you can think of, and keep it. I told Erin, going through these poems and rewriting them and looking at them takes me back to that time when they were little, better than any photo.

Zilot & Other Important Rhymes is available now!