Culture

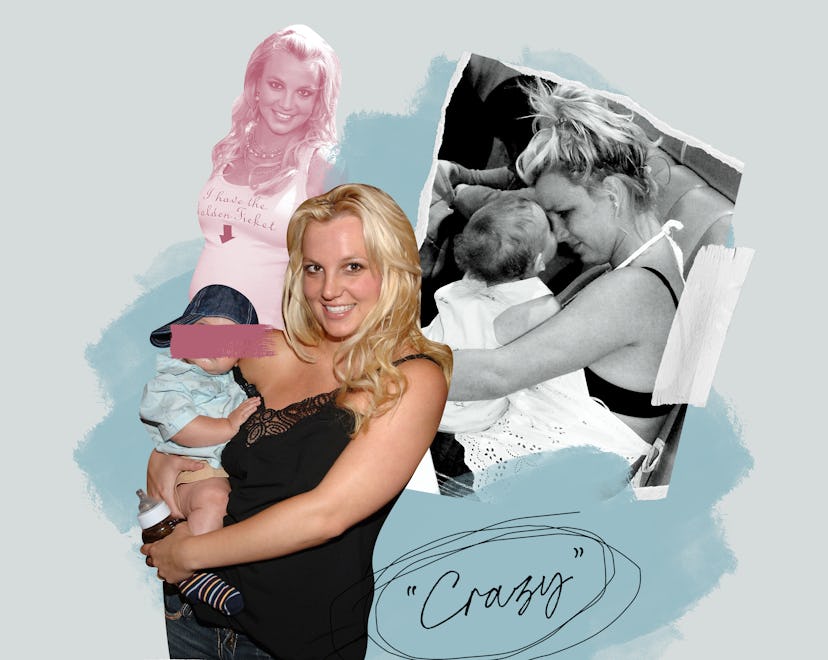

Britney Was A New Mom And No One Tried To Help Her

A friend of mine, my same age, who watched Framing Britney Spears while nursing her newborn texted me the night after I watched it. "This hits different," she said, “thinking about Britney as a mom.”

A friend of mine, my same age, texted me while she was nursing her newborn and watching Framing Britney Spears the night after I did: "This hits different," she said, “thinking about Britney as a mom.”

Britney Spears my first time was the schoolgirl, the bared belly, the writhing and suggesting, that body — "...Baby One More Time", those pigtails. I’m two years younger than her, grew up with her. She became a mother to two kids in quick succession at 24. At 28, I did the same. It all happened so quickly, time passing, but also a teenage girl growing up, transitioning to mother, is always a particular kind of shock. Young mothers can be their own type of shocking to the culture: everybody has a clear idea of what they want to see when the word “mother” is spoken, and a young, sexy, sometimes-out-late woman is not often what they want.

It feels assumed and understood that misogyny exists and destroys women. It feels further understood that this destruction becomes more nefarious and more intense when women are thought to be too sexy, too aggressive, have too much agency; it takes a different shape — this judgment and destruction — it becomes heavier, more high stakes, when women become mothers, when children are involved.

I started following Britney Spears on Instagram sometime last year. In the muddle of what time felt like throughout most of 2020, I remember only the thrill of seeing her, she who felt so elemental to my forming, a constant conversation in the culture: her silliness, the earnestness, still often the bare belly, the smudge of eye makeup, still the impressive dance moves. It was jarring how familiar and also different looking at her felt.

I scrolled back to find pictures of the children. They’re boys, 14 and 15, in that awkward teenage stage where their bodies don’t quite fit them. They’re children, I remember being maybe weirdly shocked to realize, and not really my business. I scrolled through all those videos of her dancing, of pithy self-help jargon and one straight-on photo of her face and upper torso after the next, exclamation points and lots of rose emojis, only to find the kids. I quickly put my phone down, then, thinking, of course, they’re just children; of course, she’s also just a mom.

What stood out to me about the documentary was an image of her, early 20s, a few months postpartum, smudged mascara, running to her car with her baby pressed to her chest. The day she hit the paparazzi’s truck with an umbrella was the same day she tried two times to convince Kevin Federline to let her see her children and he refused. That night with the umbrella: I was in my 20s, just like Britney. I was reckless; depressed and anxious. I often drank too much. I felt nowhere close to ready or able to have children. I remember the crazed fury I thought that I was seeing in those photos. I did not think once, not any of those times I saw them, of her as a mother. She’d lost her marriage, by then; shaved her head (also, the night of the head shaving, she’d gone to Federline’s to ask to see the children and, also that night, he refused). The night with the umbrella: her cousin drove her to ask to see them. Federline refused to open the gate to his house, to let her even up the driveway. Her children were, at that time, 1 and 2.

I’ve never met a woman who did not at some point, in those first early weeks of motherhood, break down.

1 and 2 is so particularly physical and harried, bone-deep; the sleeplessness, so many hormones: the way your body tells you you need to be with them, the terror that comes often, the need to have them close. Britney had recently lost physical custody of the children and had sporadic visitation. There’s a quick mention in the documentary that her mother thought maybe she suffered from postpartum depression, but it’s not long discussed.

Crazy, people said then, looking at those pictures. As if that word is anything besides a term that people hurl — often at women — to make clear they’re no longer useful in the way that others might have hoped or liked. There is no space inside it, that word. There was so very little space inside the conversation for any actual, individual — also perhaps hormonal and/or chemical — flaws or foibles; struggles; humanness.

Becoming a mother is a shock to the most well-built, well-supported system. It destabilizes one’s sense of self, one’s relationship to power and control. This was a 24-year-old woman tracked and followed since she was a teenager, her every move up for debate, constant fodder; a woman whose marriage would end not long after she first became a mother, a couple of months after the birth of her second child, who was born a year after the first.

There’s another clip, pre-kids, pre-Federline, when Spears is asked something about the hullabaloo around her fame and music. I’ll just get married, she says. I just want to live my life with my husband and my kids. There’s a clip — pre-babies and then post- — of two TV interviews, ones with warm lighting, institutional, clearly sanctioned by the higher-level systems of the culture. What I mean is they are not low-brow paparazzi but Dateline, 60 Minutes, places that purport to be the news. Matt Lauer (and, speaking of which…) asks her if she thinks of herself as a bad mother, if she thinks people have a right to be worried for her children. In both interviews she breaks down.

I’ve never met a mother who did not, at some point, but more often lots of points, think of and then itemize ad infinitum all the ways that she might be a bad mother. I’ve never met a woman who did not at some point, in those first early weeks of motherhood, break down.

We like our teenage girls to be attractive but non-threatening: objects that stay objects and stay quiet, attractive but not to the point that we can’t ultimately dismiss them, not so good at being objects that we feel pulled to them against our will. We like to scold our mothers for their wrong actions, not least because of how terrifyingly motherhood is about women having power, taking charge, not least because of how woefully ill-equipped or unwilling just about anyone else in our society is at trying to help.

The thing I thought the whole movie is that no one ever really tried to help her. It was so scary, all the power she had, briefly. In the early parts of her career, she made the choices for the choreography and the stage sets, who they hired; people felt compelled to shut her down. It’s one of the particularly nefarious narratives of capitalism, especially for women: the idea that wealth and success translates into agency or safety. It felt inevitable — a girl like that, and then a woman. The idea that the world might sit idly by and let her continue to make choices that subverted people’s expectations or their wants.

Say what you want about the music, this is a woman who shows up.

That any woman with power like that might also need, at some point, for someone to help her; that the world might — now that she’d gotten so much from us, in the form of money, success, and fame — be willing to allow her to put some limits on what we might wring from her in return.

They don’t talk enough, in the film, about Spears’ particular skill and also commitment to performance. Even post-conservatorship, this is a woman who’s worked so hard and relentlessly her whole life. She’s a performer, thrilling, brilliant. Say what you want about the music, this is a woman who shows up. She shows up until she doesn’t. A behavior that she’s also seemed to learn, just like so many other women, is that the only power still available to her at this point is to shut down, negate herself — her hair, her work, her dignity. To refuse.

One of my favorite things about the role of mother, as opposed to nearly every other role one might inhabit as a woman, is how free it is — those first few years, especially — of context; how wrapped up you can get inside the constant daily physicality of being a mom. Sure, you come to it with your own shit, and it’s exhausting, but, for the children for whom you are mother, when they say that word, call out in those early years: the only thing they want is you.

There are a whole world of tragedies inside that hour and change of Framing Britney Spears. A whole hour and change without her there to set any of us straight. It felt physical, the sadness of it, such a straightforward linear recounting of all the words, the slurs and accusations, that have been hurled at this woman who also, when the hurling started, was just a girl. It felt sad amidst all the other sad, what little chance she ever had to get the help she might have needed without it turning quickly into accusations, without it being held immediately against her, what little chance she had to get to be just Mom.

Framing Britney Spears is now streaming on Hulu.

This article was originally published on