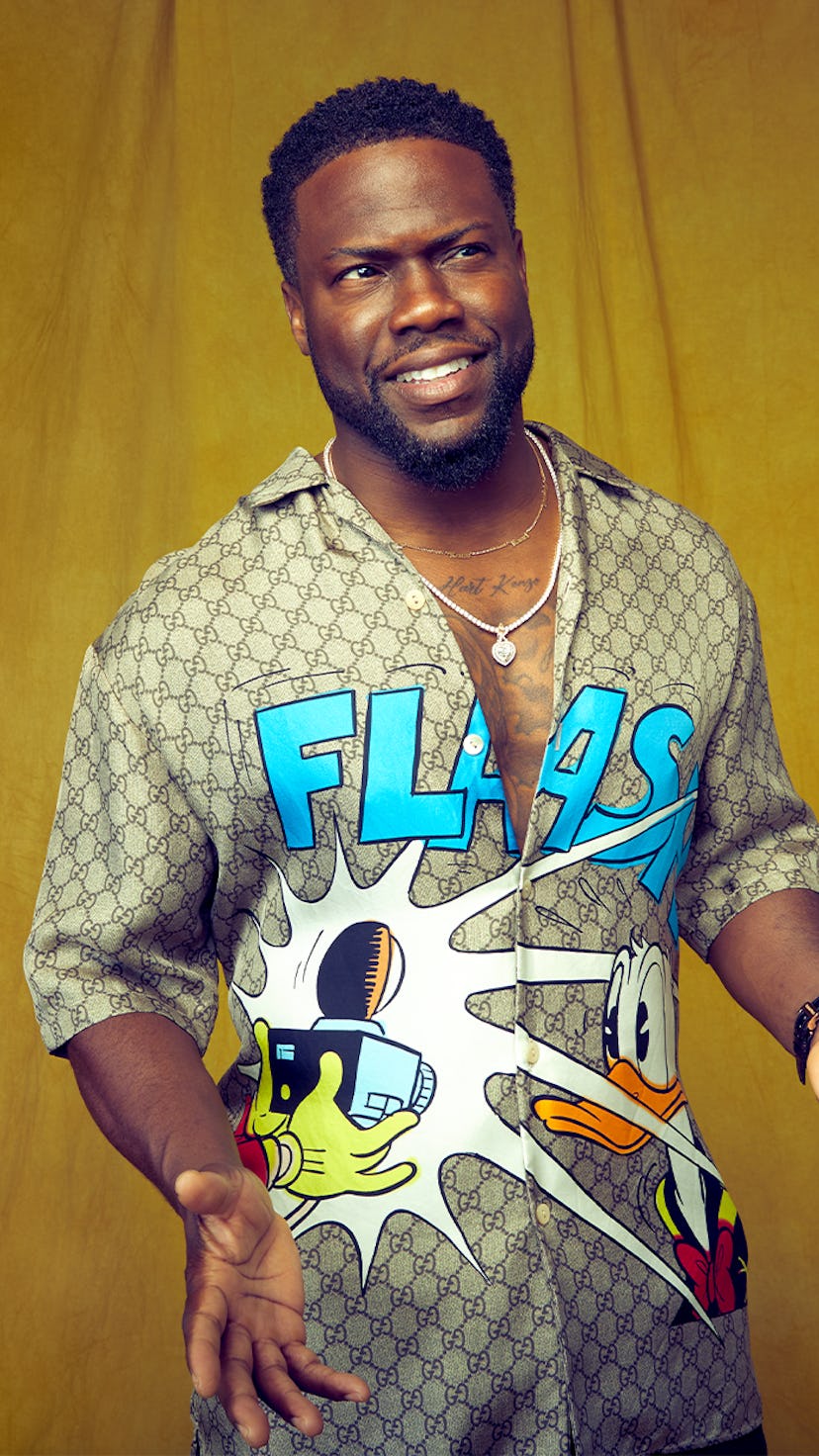

Kevin Hart Isn't The Funniest Person His Kids Know

“What I've learned as a father is that the most important thing in the world is listening. It’s not about trying to be right.”

There are many ways a celebrity could handle this situation, but there’s only one best way. When he arrived in a small village an hour outside of Montreal to shoot Fatherhood, Kevin Hart was greeted in the parking lot by dozens of Quebecois summer campers, many holding signs welcoming him. He could have hidden in his trailer. He could have posed for selfies.

Kevin Hart ordered ice cream for all of them.

There are many ways a parent could handle this situation. He could have hidden his kids in his trailer. He could have taught them a lesson about not letting the adoration of all these fans go to his head.

“He said to his kids, ‘You two are in charge of this. Go out there and make sure everybody got their ice cream,’” says his Fatherhood co-star Alfre Woodard. “He didn’t say it to the third assistant director. He put them in charge.” Plenty of guys have brought their kids to work and, not knowing how to handle the competing demands on their attention, waved the dad white flag of getting them ice cream. Hart got his kids an ice cream business. He wanted them to taste the joy of running something yourself.

This is what motivates Hart, why he can’t turn down a new challenge — a dramatic film role, cutting out red meat, starting a venture capital firm: He wants to find the one best way. Hart is a perpetual self-improvement machine. If he went to therapy — which I bet he doesn’t, unless you count his standup — it would be cognitive behavioral therapy; he doesn’t have any interest in psychoanalyzing the past. For Hart, there is no past. There is only the future, and it’s full of goals.

It’s what makes Hart, 41, the hardest working man in showbusiness. He’s starred in 15 movies in the last seven years, including the year he couldn’t shoot because of the pandemic. His resume requires a snorkeling breath before spitting it out: He hosts E!’s Celebrity Game Face; stars in three unscripted online shows (one where he works out with celebrities; one where he disguises himself as an old man and drives a Lyft; one where he rebuilds muscle cars); runs a production company (which makes FX’s Dave); breaks ticket sales records on his standup tours (he packed 53,000 people into his hometown’s football stadium); writes books (this year, the self-help audiobook The Decision: Overcoming Today’s BS for Tomorrow’s Success and the illustrated middle-school book Marcus Makes a Movie); dispenses motivational messages on Coach Kev on Snapchat; hosts a Sirius radio interview show with comedians; maintains the 21st most followed Instagram account and the 44th most followed Twitter account; and invests in Clubhouse, Masterclass, and something called “Super Coffee,” which may explain how he does all of this.

So it’s not surprising that Hart assigns his kids tasks, just as his single mom signed him up for swim classes and everything else she could. Ice cream distribution wasn’t the only work they had on the Fatherhood set. “He made them find out everyone’s name and what their job was. If they got them all right, I think they won something. It was a great way of learning about film sets,” says Fatherhood director Paul Weitz (About a Boy; Mozart in the Jungle). “I have my kids come to set, and I wish I had that idea.”

Hart has been a dad since he was 25, and he has four kids now, one son and one daughter from each marriage: Heaven, 16; Hendrix, 13; Kenzo, 3; and Kaori Mai, 9 months. He became a more present parent after he was a passenger in a near-fatal crash in 2019 in which Hart’s 1970 Plymouth Barracuda went off a Malibu cliff smack into a tree, leaving his back so mangled that family members slept in his hospital bed with him so they could push the nurse call button that Hart often couldn’t reach. He’s still got a couple of nannies to take the kids to their activities, but when he’s not traveling for work, he’s home for (cellphone-free) dinner and closes his office at 3 p.m. After he finishes an out-of-town movie or a comedy tour, he blocks off a month at home. He’s managed to co-parent with his ex-wife in spite of a painful public breakup. During the pandemic, they agreed on safety rules and had kids continue to switch houses; they didn’t even have a blowup after his house had a minor bout of COVID. As he does with nearly every project, his kids are going to visit him here in Budapest, where he’s Zooming with me from a surprisingly small hotel room that he’s barely in long enough to sleep while he’s shooting Borderlands, a sci-fi movie based on a video game and co-starring Cate Blanchett.

“I’m the cool dad,” Hart says. “But it’s not like dad is the funniest person. They’ve got a list of people funnier than me. My kids are on YouTube, they’re on TikTok, they got a whole new generation of people that they love.” None of whom he knows. “The fact that gamers were able to make this their career is amazing. Things evolve, so I don’t judge it... I don’t mind that my kids spend time doing it, but I’m not watching a person play a game.”

Even if they’re not exposing him to new parts of the culture, he makes sure to do that for them, from seeing Budapest to knowing how to deal with money. He wants to make sure they grow up with the information he didn’t have access to growing up. “Unless you are familiar with where I come from, you would truly be ignorant to the lapse of information. All you know is check-cashing places and paying people to get your money,” he says. “Now I’m privy to [so much information], which makes them privy to it... Understanding the importance of having your money work for you and being able to get low interest rates. It’s about talking to them at a young age.”

But really, he says, so much of parenting is not talking, a lesson that he — someone who motormouthed out of trouble as a kid and into a career as an adult — had to absorb through observation. “What I’ve learned as a father is that the most important thing in the world is listening,” says Hart. “It’s not about trying to be right. It’s not about advice. It’s about listening, understanding, and then doing your best to give information so that your kids can make the best choices for them. Not for you, but for them.”

It’s a principle he’s imported to his work, where he manages people at his many jobs. “When people are just listening for you to stop so they can talk — I don’t do that. I’m processing what’s being said. That’s the most important thing, giving an opportunity for each individual to be heard,” he says. At home, he established a “free-speaking zone” that gives each kid the ability to tell him something without him getting angry. Though if they abuse it to get out of trouble, they lose their free-speaking zone rights.

“I’m the cool dad. But it’s not like dad is the funniest person. They’ve got a list of people funnier than me.”

Conveniently, active listening also happens to be the key to acting. Especially in dramatic roles, such as the dad in Fatherhood, which was about to be released in theaters shortly after the pandemic hit but will now premiere on Father’s Day weekend on Netflix, presented by the Obamas’ Higher Ground Productions. The movie is based on Two Kisses for Maddy: A Memoir of Loss and Love, the viral blog turned 2011 New York Times bestseller by Matthew Logelin. Logelin wrote in real time about raising his daughter after his wife collapsed from a blood clot 27 hours after childbirth and died. She had been his high school girlfriend and became an executive at Disney, while he followed her around the country and struggled with his career. After she died, he took his daughter to India and Nepal, where he had proposed to his wife, and to Mexico, trying to keep her memory alive in his daughter.

This character requires even more listening than most. As a single dad, he is bombarded by everyone’s advice on how to parent. Hart’s ability to listen is what Weitz noticed as soon as he talked to Hart about the role, which had been slotted for Channing Tatum, who remains an executive producer on the film. “Kevin is able to enjoy being in the moment. That’s often hard for comedians. So much of what they do is use other people as a sounding board. To react to Alfre Woodard and also to a 7-year-old kid is really impressive,” Weitz says.

That’s partly because he treats kids like adults. He treats everyone like they’re an adult. Unlike his manic, self-deprecating onstage act, Hart is serious, earnest, calm, and stubbornly positive. “A lot of comedians found a schtick or they would have withered in childhood,” says Woodard. “For him to take this moment and find the full spectrum of his acting ability to give himself more range than he has allowed himself, I was happy for him. What would his life have been like if he’d shown this tenderness as a child or when he first went to New York to get onstage?”

Probably even harder. Hart grew up in a tough section of Philadelphia, and his father, who was addicted to drugs, spent much of his childhood in prison and the rest of it away from his family, except for when he robbed Hart’s older brother’s barbershop or broke into Hart’s mom’s house to steal money.

His father is sober now and part of Hart’s kids’ lives. I expect Hart to tell me a story about forgiveness, but forgiveness is backward looking. A well-oiled perpetual self-improvement machine skips right to acceptance. “It’s not about making up for the things that he can’t change. It’s about enjoying the present, being a great grandparent. I don’t like to focus on things that you can’t change,” Hart says. “If you’re about solution, sometimes solution is finding a happiness in forward progress.” As Weitz explains it: “He’s able to shrug things off. This is a strange word to ascribe to him, but he’s Zen-like in his ability not to dwell on bad things that stress people out.”

Dwelling would be more than understandable. Hart has experienced his share of bad things that stress people out, and not only in his childhood. He received three years of probation for a DUI after he nearly smashed into a tanker truck in 2013. (When I interviewed him right after that, he told me his solution was to hire a professional driver and buy a Sprinter.) He stepped down from hosting the 2019 Oscars after his old homophobic tweets were dug up. In Zero F*cks Given, the Netflix standup special he shot in his living room in November, he joked about his lack of privacy by saying that after announcing he stopped eating red meat, someone shot a video of him in his car eating a Big Mac. That video doesn’t exist, but he may have been alluding to the fact that a friend threatened to blackmail Hart with a video of him in Las Vegas cheating on his wife while she was pregnant.

Even this beastly scandal that your kids will find out about online — there’s one best way to handle it. It’s not hiding in your trailer. It’s not buying your kids ice cream. “You have to talk to your kids about it because it’s going to come out. And some of them are cool about it and some of them are not, depending on the situation. You have to understand the different personalities and manage them correctly,” he says. “My kids understand who their father is. And, unfortunately, there’s a gift and a curse that comes with that. The gift is the life that you’re able to live, and the curse is the spotlight that’s on you constantly.”

It’s vulnerable having the world know parts of you that you’re not proud of, and even more vulnerable having the world tell your kids about those parts. And still maintain your role as an authority figure protecting them. The struggle between vulnerability and toughness is the main theme of both Hart’s standup and of Fatherhood. He says the first joke he told in his own voice in a standup routine was about calling the cops after he and his first wife got in a fight, and crying while telling the police that she hit him. It was unimaginably far from the macho posture of the HBO special that inspired him to become a comic, Eddie Murphy’s Delirious.

Hart taps into that vulnerability to play Logelin, who is otherwise not much like him. Logelin is a shy, goofy, white guy whose post-college philosophy, he writes in his memoir, could be summed up by a T-shirt he saw on a homeless man that said “The Working Man’s A Sucker.” Hart, who wakes up at 5 a.m. to work out and once entered some insane relay race in Oregon in which he ran 18 miles over 24 hours and slept in a van, found Logelin’s introverted self-doubt. “He got that part of me. My wife was the outgoing one. She made friends easily, and I hung back and did what I could to make her happy. Thirteen years ago, before my wife died, if I was told I’d be talking to you, I’d be hiding in the corner crying,” says Logelin from his house in L.A., where he lives with his new wife, Bob’s Burgers writer and The Great North co-creator Lizzie Molyneux, the daughter they share, and Maddy.

“My kids understand who their father is. And, unfortunately, there’s a gift and a curse that comes with that. The gift is the life that you’re able to live, and the curse is the spotlight that’s on you constantly.”

In the movie, unlike in real life, Hart’s character has a tense relationship with his mother-in-law, played by Woodard, who thinks she should raise Maddy. And he struggles more to realize that parenting is more reactive than proactive. “Fatherhood only gets celebrated in ways that are muscular,” says Woodard, lamenting dads who tell their kids to walk off a bruise instead of holding them. “The thing about muscle is you can’t hug it. It’s useful but it’s not lovable.” Alternative versions of fatherhood don’t get portrayed a lot. In fact, no versions get a lot of attention. “We talk about mothers, mothers, mothers,” says Woodard. “We talk about mothers so much because we haven’t given women credit for being full human beings so we overdo the thing of lauding moms.”

Showing the softness of Black dads, Woodard says, is particularly verboten. “Our culture wants to be terrified of Black men because they’re afraid of how they tried to subdue their power. So as an industry, we’ve perpetuated that fear because the business knows it sells. That’s why the dominant culture has no idea of the depth of involvement and mentoring that Black fathers have done for generations.” Putting a more complete version of Black fatherhood on screen, she explains, requires reckoning with why past portrayals are so narrow. “That’s why these conversations are tough. You skip over history and say we’re all post-racial. You feel that itch in your clothes because something hasn’t been accounted for.”

That itch is tough for Hart. Confronting and fixing racism is a project that doesn’t have one best way to handle. A perpetual self-improvement machine isn’t built to deal with systemic issues. The epigraph of his autobiography, I Can’t Make This Up, is from Socrates: “Let him who would move the world first move himself.”

He could hide in his many trailers and ignore it. He could post positive messages about racial conciliation on his social media accounts.

Hart never figured it out. The thought of sitting down and watching the George Floyd murder with his kids repulsed him. “‘Hey, kids, let’s watch a dark death video. This will be good family time.’ No, that’s not that we're doing,” he says. Like with everything else, he wants them to have information, to ask questions, to work on solutions themselves, to let them enter the free-speaking zone. “The sad part is as a parent you don’t have answers. You don’t have the answers because you’re not seeing effort from the masses.”

He understands how hard this will be for them, but he wants his kids to wrestle with this. If there’s one thing Hart can’t understand, it’s a lack of effort.

Shop The Looks

Top Image Credits: Disney x Gucci shirt, AMI pants, Hart’s own jewelry and watch

Photographer: Gizelle Hernandez

Stylist: Ashley North

Groomer: John Clausell

Art Director: Erin Hover

Set Designer: Robert Ziemer

Bookings: Special Projects

Videographer: Sam Miron

Joel Stein profiled celebrities as a staff writer at Time Magazine for 20 years. He has also been a columnist for Entertainment Weekly and the Los Angeles Times and is the author of Man Made: A Stupid Quest for Masculinity and In Defense of Elitism: Why I'm Better Than You and You're Better Than Someone Who Didn't Buy This Book. He appeared as a talking head on I Love the 80s and any other TV show that invited him on.