Books

Our Castle Year: The First Home I Made For My Boys After Divorce

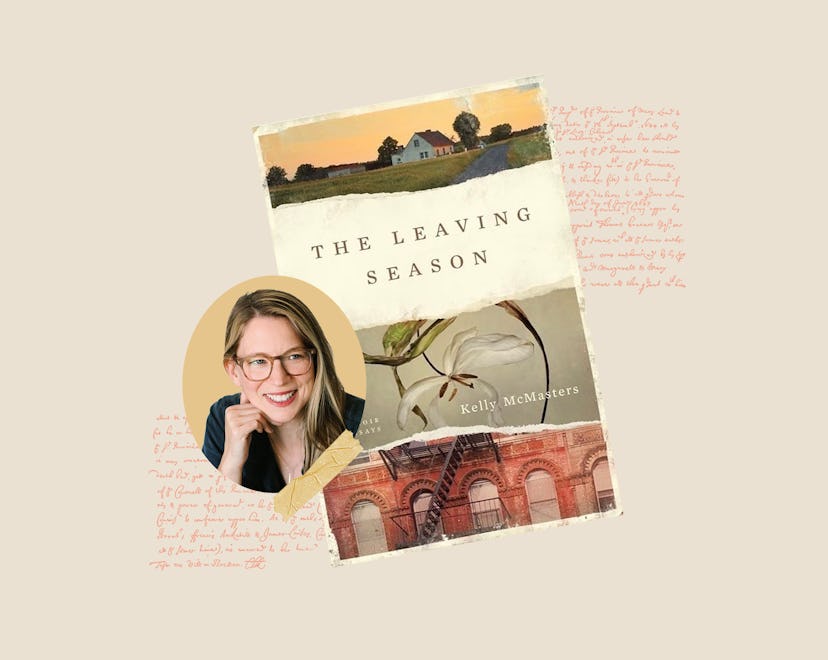

In an excerpt from her new book The Leaving Season, Kelly McMasters chronicles how she built a new life after the one she had dreamed of slipped away.

Our new home in Lancaster is made of stone. The renovated carriage house sits at the edge of the Lancaster County Historical Society, and I tell the children the museum’s expansive leafy grounds are our backyard. The carriage house is carved up into four apartments, and ours is on the ground floor with a lovely porch and sliding glass door. Our apartment, we will discover, has very little heat, but novel luxuries like a dishwasher and a converted silo we turn into the playroom make the place feel magical. At the conical tip of the silo’s cylinder is a small iron flag; we’ve never been, but it reminds the children of pictures they’ve seen of Disneyland, and my youngest calls this home our castle.

Their new school is two blocks in one direction, located in the old clock factory at the end of a lush tumble of gardens and stately homes. The college where I teach is five blocks in the other direction. The first time I see my name on the office door, I enter the small room and weep for my good fortune. I don’t even realize the office has no windows until another junior professor points this out. The room has wraparound bookcases and a giant old-fashioned desk under which my children curl with blankets and snacks when they are home sick from school and I need to bring them to work with me.

The place is perfectly manageable for a single mother pretending not to be a single mother.

The boys learn chess in their aftercare program. They come home with a paper board, lay it out on our table and proudly name the pieces, telling me how each one moves, their special powers. Usually, the game devolves into a fight between the horses. They are called knights, Mama, they admonish. I am learning, too, I remind them.

We stare into the houses, pick out our favorite future homes. We decide to live right next to each other in a row, to always be near.

I don’t like the way the sets of kings and the queens sit so primly across the board from one another, the way each piece has its defined place. I enjoy the moment when the game turns silly and the squares become a great lawn or forest, instead of a regimented blueprint for the required structure, a married couple and their spawn. Pawn, Mama, they correct. Not spawn.

In New Ways to Kill Your Mother: Writers and Their Families, Colm Tóibín says that in creative writing, “mothers get in the way.” He argues their connection to their children renders mothers too difficult for juicy plot. “They take up the space that is better filled by indecision, by hope, by the slow growth of personality.”

In Lancaster, I cannot afford to bother with indecision, or with hope. Instead, I keep the shades of our stone house drawn and sit in the middle of the round playroom while the children circle around me. I keep them close, and I keep smiling. We tape their paintings on the walls, blow bubbles indoors. They are so small that time is still elastic, so I can mold our world without attending to logic, or truth. We will see their father “later,” we will be staying in this new place “for now.” It sometimes feels cruel to distract them with ice cream or a drive to see the baby animals at the Amish farmstand down the road.

On the days the children stay late so I can teach, they emerge from their clock factory school chattering happily. We walk the short distance home, taking care over the section of broken sidewalk we call the roller coaster because of the way the tree roots have forced the concrete up and out. We stare into the houses, pick out our favorite future homes. We decide to live right next to each other in a row, to always be near.

The chess vocabulary spills out of them on these walks. There are King’s leaps and captures and home squares. When I hear the word castle, I think they are talking about our apartment. But no, the youngest tells me. The move is named this because the rook looks like a castle.

When a player castles, they move their rook from the outside of the board into the middle, trading places with the king. The king then gets tucked nearer to the corner. I ask them why they would put their little rook out there in the middle like that.

Running away is different than leaving.

They shake their heads impatiently. Castling is the best protection, they say matter-of-factly. It sounds more to me like sacrifice, but I keep my thoughts to myself.

When we walk up the driveway to our apartment complex, we look at the stone silo with new eyes. The three of us see it at the same time. Our new home looks like a rook.

Much of motherhood is deciding how to mete out the world’s cruelty. Some days, I feel like The Giver in Lois Lowry’s seminal young adult novel of the same name. The dystopian coming-of-age tale weaves the story of a society in which emotions are regulated so that there is no sadness or pain; all memories are held by a single person, and the main character, Jonas, is chosen at the age of twelve to take on these memories, to be that single person for the community. The Giver transmits these memories to Jonas in daily sessions that quickly verge on torture, though these memories are simply truths about our world that most of us already know. I find myself making similar calculations as I decide what and how to share with my children: How much pain do I inject into them today and how much can I stave off for another week, or month, or years?

The college students I teach adore The Giver, seem to wish they could be tested in the way Jonas was, as the old man puts his hands on the child’s back and transmits the world’s memories to him. For so many of them, it is the book, the book that set them on a course to my creative writing classroom. But when I read it, I am horrified. I chalk this up to my coming to the book as an adult, rather than as a child — The Giver was published in 1994, the year I graduated high school, so by the time I check it out of the library I am far from its intended audience.

The idea of forcing memory onto a child turns my stomach. I do not want to transpose my memories onto my children, even the ones for which they were present. In our stone castle, I instead work on making new memories. We play soccer in our parking lot, search for turtles in the Historical Society pond, build gingerbread houses for the very first time; and our Christmas tree is a potted shrub, though still taller than my sons, its decorations made of construction paper rings we loop around our wrists in the playroom.

Mostly, the children are fine. But I am vigilant in searching for signs of distress. My oldest comes home from school each day with a square of fabric and a button sewn into the middle. He chooses to do this work, as they say in Montessori, and I am alarmed, worried that he is using the solitude and repetition to quell anxiety. It will not be the last time I project my own behavior onto him. When I observe his classroom one afternoon, I see him go to the sewing corner, where he sits alone like an old woman, so expert now that he doesn’t even have to look at his fingers as they swiftly handle the needle and thread. Instead, he watches the groups of children and his teachers, listening to their chatter and recording their movements in his head. He is not isolating at all; this is his way of being with people, I consider. He knows who had a bad day and who loves math and who got a new baby brother. I’d thought he was learning these details because he was engaging the other children, talking while playing or at circle time. Instead, he is like a spy, and when he returns home each day he tells me all the things he learns and I fish out the new button-work from his backpack. We hang his squares of fabric on a clothesline that soon stretches the length of the living room wall.

The first time I tried to leave the house where we lived with their father, I took the children to my parents’ house. After hushing them to sleep upstairs, I joined my parents on their big leather sofa in their perfectly appointed living room. I told them I did not want to go home.

My parents listened quietly. When I was finished, they put on the tea kettle. We sipped tea into the night while they explained that I could not stay. That I had to go back to that house and my husband. That I had to return with my children.

If you stay here, they said, you’d just be running away. That’s no way to leave.

It had never occurred to me that they would not let me stay. Instead, two days later, they helped me repack my bags and load them into the car. They watched as I clipped my children into their car seats and backed out of their driveway.

For years I didn’t understand. But now that the boys and I were living in our castle, with an arboretum as our backyard and our own health insurance and a CSA box we picked up from campus every Thursday, I understood.

Running away is different than leaving.

When my father plays chess with my children during his visits to our apartment, he is impressed that they know about castling. He counsels them to use this as part of their opening strategy, to play defense before offense. My youngest parrots him, calling the move crucial.

My father never taught me how to play, but he brings a travel chess set when he comes to visit so he can play with his grandchildren. He teaches the boys how to lose, how to shake hands over the board. He teaches them how to think three steps ahead. He teaches them how to protect themselves. Sacrifice, I learn, is sometimes the best strategy.

About five months after moving to Lancaster, I was back on the job market again, since my position was only secure through the end of the school year. I graded papers into the night and juggled freelance work, barely sleeping, though I still felt that I could burst with joy each time I opened my kitchen cabinets and saw my glasses and mugs stacked the way I liked them to be stacked, their mouths open in a small hopeful chorus.

When my next job comes through, it is a bittersweet relief. The new position holds the promise of tenure, and will take us to Long Island, closer to friends and family. And yet, we’ve grown to love Lancaster, and none of us wants to move again. We are all tired of leaving. But time is still elastic. I continue to mold our world and our truths to make them softer, gentler for the children. I’m not sure how much longer I will have this power, but for now, I wield it gratefully.

In The Giver, Lowry writes, “The worst part of holding the memories is not the pain. It’s the loneliness of it.” In that stone castle, we rebuilt our story. Together. We shared the same memories. We loved our schools and the market and the rounded walls of the playroom. But stability meant more than comfort to me now. “We gained control of many things,” Lowry writes of the society’s choice to mute emotions. “But we had to let go of others.”

By the end of the year, I knew the names of all the chess pieces and what they could and could not do. I watched my children’s strategies on the board, tried to understand their minds through the ways they moved their pieces. For much of their lives so far, I’d seen them as a unit. This year, though, they’d begun to differentiate, from one another, from me. One prefers vanilla, while the other only eats chocolate ice cream. One loves bright colors and pattern, while the other will only wear plain shirts. One reliably opens each game by castling early, while the other hangs back, saves the move for later.

Much of motherhood is deciding how to mete out the world’s cruelty.

One afternoon, my youngest has me cornered on the board. We are playing our game on top of a moving box, one of many spread throughout the stone hall of our apartment. Sound becomes more echoey with each item we pack. I castled early in the game, but now I am in trouble, my king under attack, and so I castle again.

My son yelps, tells me I can’t do that. He explains that once you move your rook out of castle, the protection disappears. It’s like a magic spell that has been broken.

“The castle is gone,” he says with such certainty. “You can never castle again.”

Looking around at all our boxes, the finality of his statement makes me want to cry.

On one of our last mornings, a small voice cuts a jagged line into the quiet of daybreak. My body reflexively lifts out of bed, finds its way over the piles of tiny cars and books and socks, through the stone darkness of our apartment, what will now simply be our first without their father. I steer myself into the bedroom the boys share, see it is my oldest who is awake, find his bed, crawl in.

“Mama,” he repeats, softer this time. His eyes are wide and staring. “What’s inside my bones?”

His body is taut beneath his duvet and the nightlight hollows his eyes grey. He is five. He loves ABBA, the beauty of photosynthesis, the number zero. He is small for his age, can’t yet tip the old brass scale past thirty-eight pounds at swim lessons. He is sharp-edged, ungraceful; holding him feels like putting my arms around a folding chair. I murmur about minerals and marrow, picturing the mealy silt sealed inside his spindle legs.

My hand rests on his sternum, thrumming with his heartbeat. He lightly moves it away. He weighs what I’ve given him, half-remembered fragments about blood cells and tissue.

But it’s enough, for now.

His body relaxes beside me and his breathing goes hard, like his brother’s across the room. I stare at him as the light shifts through the blinds. The translucent skin on his eyelids gives a faint ripple, the thin purple branches of blood vessels pulsing like a secret between us.

What’s inside your bones, sweet boy?

I am.

Excerpted from The Leaving Season: A Memoir in Essays by Kelly McMasters. Published by WW Norton. Copyright © 2023 by Kelly McMasters. All rights reserved.

This article was originally published on