Incredible Humans

Stacey Abrams’ Word For 2022 Will Give You Hope

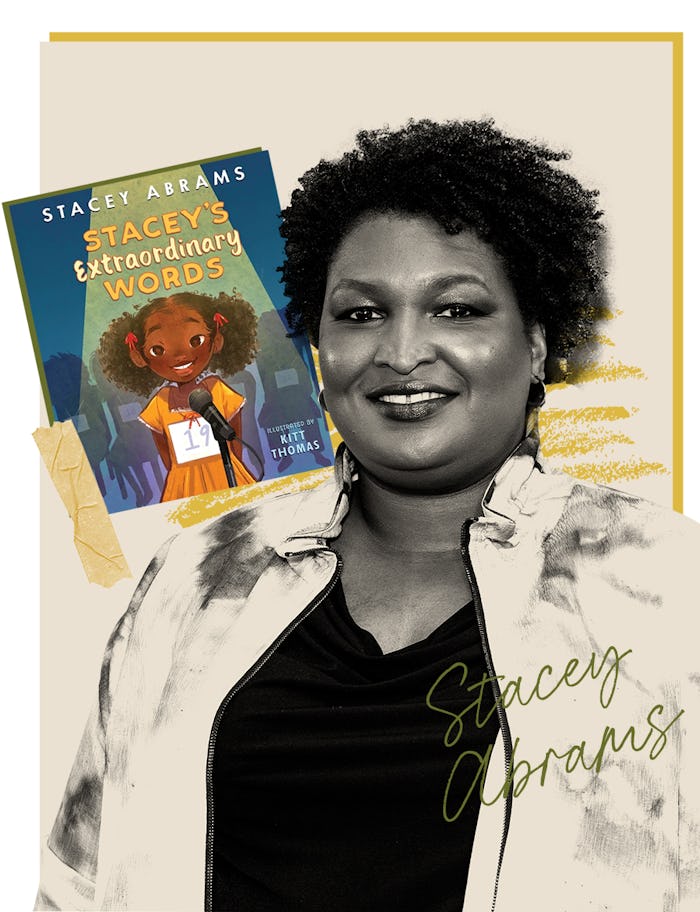

Stacey’s Extraordinary Words is a delightful, entertaining children’s book based on Abrams’ own childhood.

“Not only were words my companions, they were my protectors,” writes Stacey Abrams in the author’s note of her latest publishing triumph. “I learned how to use my words to do good, even when I am most afraid.” But the voting rights activist, New York Times bestselling author, and 2022 candidate for the Georgia governor’s seat isn’t talking about a moment from her substantial political career or even from her time at Spelman College or Yale Law School. She’s referring to her childhood when, as a little girl, she and her siblings would go to work with her mom, a librarian, and take naps among the stacks of books. Hers was a childhood spent enduring the taunts of bullies and harboring a fear of making mistakes — but that also involved taking refuge and comfort in the pages of a good book and finding her voice and her courage on the small stage of her elementary school’s spelling bee.

Abrams, who has published two nonfiction books and one thriller under her own name and multiple romance novels under her nom de plume, has now authored Stacey’s Extraordinary Words, a delightful, entertaining children’s book based on Abrams’ own life. The title of the book is a smart turn of phrase — it turns out to mean both the words that young Stacey learns and the words she finds within herself. The story, gorgeously illustrated by Kitt Thomas, is not only a love letter to readers who know that words are a gift but an invitation to all into the world of possibility.

Below, Romper chatted with Abrams about the book, her advice for parents who feel despair at the state of the world, and what she’d say to her younger self if she could go back in time for just a few moments.

Romper: What inspired you to write a children’s book? Why kids as a target audience?

Stacey Abrams: Well, I, first of all, love and respect children’s literature. When I was growing up, my mom was a librarian by training. She was a research librarian who had a specialty in children’s literature. So, I grew up, as did my siblings, surrounded by not only books but by children’s books of all kinds. As a young person, of course, I loved them, and as an adult, I really admire and respect the craft it takes to write an engaging children’s book. You’ve got to take these complicated ideas and not only reduce them to fewer words but do so in a way that doesn’t underestimate or disrespect how inquisitive and facile young minds are. And so, for me, this was an amazing challenge, to get to tell a story that kids could love and that parents would like reading to kids. That, to me, is the sort of balance you want to strike, that the kids love it but that the parent who has to read it 15 to 38,000 times actually doesn’t get bored every time.

That sense of responsibility, that kindness and compassion that I watch my parents embody every day, is my guiding star of how I want to be perceived and how I want to be judged.

As someone who has spent many hours reading the same book out loud, I can say that’s a very thoughtful way of thinking about it. Is there some reason you wanted to speak to children in particular at this moment in time?

I have six nieces and nephews, and they range in age from 5 to 16, but four of them are between the ages of 5 and 9. They all live in Atlanta, and I’ve gotten to spend a lot of time with them over the last two years, during the pandemic. They watched my campaign in very different stages of awareness. One thing I thought about [in conceptualizing the book] was: How do you talk about losing and failing to achieve your goals at the same time that you encourage them to be hopeful and to persevere? And this book, for me, was a way to frame those conversations in very real terms.

Perseverance is a strong theme of the book, and it’s certainly been a theme in your career, thankfully. We all thank you for that! Where does this determination and resilience that you have come from? Is there something your parents did to help foster those qualities?

My mom and dad, they’re amazing people in and of themselves. And even before I was old enough to know what I was seeing, I watched them grapple with the complexities of racism and sexism and poverty but to always do so with this kindness and this compassion that, really, I think, affected all of us. I talk about how my parents would take us to volunteer, and we would go to soup kitchens and homeless shelters. And we would point out “We’re poor. The lights are off at home” or “We don’t have running water.” And their belief was that that was not the metric of whether you were required to help. It wasn’t what you had or didn’t have. It was what was needed. And that sense of responsibility, that kindness and compassion that I watch my parents embody every day, is my guiding star of how I want to be perceived and how I want to be judged. Am I a good person trying to do good for folks every day?

So, it was really more who your parents were and what they did rather than anything that they said to you in particular?

Well, I would say it’s a combination. So, their response when we would say “We’re poor,” the response was “No matter how little we have, there’s someone with less. Your job is to serve that person.” When we stumbled or made mistakes, they would encourage us to try again… My mom is a librarian and my dad is a storyteller. My dad used to tell some very complicated bedtime stories and my mom used to read to us. They would read us stories about perseverance and about making mistakes and all those great stories of people who met challenges and didn’t always succeed, but that didn’t stop them from trying.

Are there any books from your childhood that were particular favorites?

When I was really little, my two favorites were Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears —

I don’t know that one!

It’s so much fun! It is, and the images — I remembered the pictures more even than the story. And then Make Way for Ducklings was our collective favorite. There are six of us, so we were the Make Way for Ducklings.

And then, as I grew older, probably, when I was reading more chapter books, I loved The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, about Milo, who gets caught in this world, in this battle between words and numbers, and has to figure out how to help resolve the talents of these two kingdoms.

I love that book! I love it. You are obviously very experienced in writing books for grownups. Is there anything that surprised you about the process of writing a children’s book?

It’s hard! For a book about words, it was incredibly important to pick the right words. … When you have 115,000 words to play with, or 75,000 words, you have time to build out, in detail, what you want the reader to take in. In a children’s book, you have to condense the words, if not the ideas, and as I said, you have to be respectful of the capacity of a kid’s mind to take this information in, and you never know how they’re going to process it. And so what I found both exhilarating and challenging was translating my fondness for storytelling into a story that had fewer than 1,000 words. And I had to get all of it across in a way that is acceptable and didn’t speak down to kids but wasn’t so over their heads that it was meaningless. And because I love words, also find a way to bring in those really big words, but give them context so that they could enjoy the experience of learning and listening and reading.

Each day, as hard as it can feel, is a chance to do something that you think you should do, a chance to be someone that you like.

Tell me about the collaboration with the illustrator, Kitt Thomas — that’s such an important part of a children’s book. How was that process, and what was most important to you in terms of how they captured your story?

Kitt is exceptional. There is something extraordinarily gratifying about having an illustrator in collaboration with you because when you’re writing adult fiction, or even adult nonfiction, it’s all about the words on the page. What they did was take these words and the story and animate it in a way that exceeded my expectations. The frames where the spelling bee is happening, and Stacey and Jake are back and forth with their words — just how gorgeously rendered that is, and how vibrant and alive it feels, is something I couldn’t have imagined as a writer. But when I saw it on the page, that was exactly what I would’ve wanted.

And you both, in collaboration, really captured that feeling. I was brought right back to my spelling bee moment of 35-something years ago. I still remember! I wanted to ask you: Like Stacey in the book, was “instantaneous” a spelling bee word that you misspelled in real life?

It was not. I misspelled “chocolate.” [Editor’s note: Just like another character in the story.]

You were the “chocolate”!

I was the one. I refused to fully relive my own misspelling, but yes, I included it in the book.

I am still mad. Mine was “lilac,” and I knew how to spell it, but I just got really nervous and the lady pronounced it “lie-lick,” so I spelled it that way, with an I!

I grew up in Mississippi. I never realized there was a second O in chocolate. I knew there was no K. I knew it wasn’t C-H-O-C-K-L-A-T-E, but who knew that the other letter was an O?

I bet anybody who’s ever lost a spelling bee remembers their word.

Yes.

Oh, boy. Going back to the theme of children — obviously, everyone has had a hard couple of years, but kids really have, in particular. Is there anything that you’d want to say to them on behalf of the grownups who are supposed to be in charge right now?

[This is] part of what I try to do at the end of the book. When Stacey’s mom says, “There’s always next year” — [conveying the idea] that the contest is what matters and “you can come back and try again next year to win” — I wanted Stacey to say, “No, there’s always tomorrow.” Because it's hard to imagine — especially when you’re in [the] midst of a pandemic that doesn't seem to end — this idea that there is an eventual termination date, that things are going to change. Instead, it’s about just making sure that kids know that each day can be made better. Each day, as hard as it can feel, is a chance to do something that you think you should do, a chance to be someone that you like. You can try things every day, and you don’t have to wait until everything is fixed because we don’t know when that’s going to be. We don’t know what’s going to happen in the next contest, but we have control over the next day, and the next hour, and that’s where we should keep our attention.

Many parents are really worried sick about the future of our country, of the planet, the future that our kids are inheriting. What’s the No. 1 thing that you would tell a parent who wants to take some action to ensure that future and protect it?

Pick the issue that animates you, the one that keeps you awake at night or wakes you up in the morning, and focus your attention there. There is such an instinct to be overwhelmed by the sheer breadth of what we say, and it becomes so big that we can’t figure out how to do anything about it. And instead, what I say is: Find this thing that you can do and then find someone who is doing it, and ask how you can help because, especially if you’ve got kids, you don’t have time to try to create something new. You’ve got full-time jobs already, but by adding your smarts and your enthusiasm and your work to someone else’s, you’re building on good and you’re bringing your own good to it. It also helps us not scale down our ambition but bring our ambition into focus.

We’re not going to solve climate inaction that has stretched over centuries in a decade, but we can do something to mitigate it now. So, what is that thing, if that’s your issue? If poverty is your issue, if the inhumanity we have seen against children is your issue … St. Augustine called it “a restless heart,” that thing that keeps you restless and keeps you worried, that’s the thing you want to focus on. Don’t try to do everything. Give yourself permission to do one thing and to do what you can in that space.

Do you have a word for 2022?

Well, my favorite word is syzygy — S-Y-Z-Y-G-Y — because it is a word that has no regular vowels.

That’s a good Hangman word!

Exactly, exactly.

What does it mean?

And that’s the other reason I love it. It’s when three or more objects line up so that if you look at the object in front, you can’t see what’s behind it. It’s usually in reference to celestial bodies like when the Earth, the moon, and the sun line up in syzygy, but it’s a phenomenon when you can see the thing in front, but you can’t see what’s behind it, but there is something there. It’s always my favorite word, but it will be my favorite word for 2022 because … while we can see what’s in front of us, we can’t see what’s already lining up next — but that doesn’t mean good isn’t coming. We just have to keep waiting for the alignment to shift, so we can see what else is there.

Along with your author’s note in Stacey’s Extraordinary Words, there is a childhood photo of you. How old are you in that picture?

I am 5.

If you could go back in time right now and tell that little 5-year-old self something, what would you tell her?

Life is even more fun than you think.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on