books

Are We Ready To Talk About The Year That Covid Stole From Our Kids?

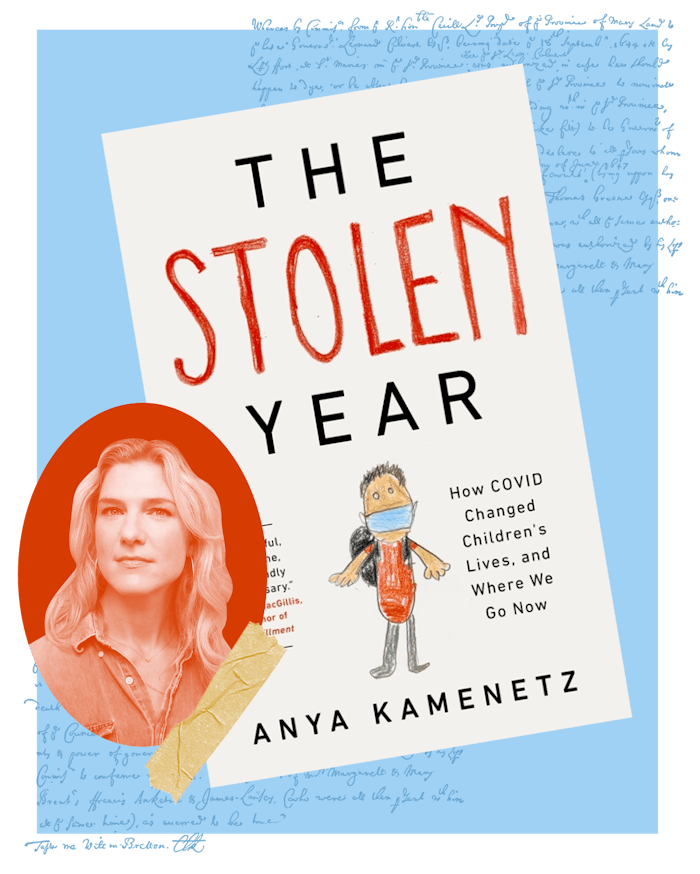

In her new book, The Stolen Year, Anya Kamenetz asks the question on every parent’s mind: How did the government manage to fail children so spectacularly?

In her new book, The Stolen Year: How Covid Changed Children’s Lives, and Where We Go Now, former NPR education reporter Anya Kamenetz seeks answers to the question on the minds of so many of us who parented through the pandemic: Why and how did this country fail to put children first?

The book is deeply researched and reported with page-turning prose that plucks more than a few raw nerves. Kamenetz achieves this balancing act by documenting both the shared timeline of 2020 to 2021 and the individual stories of a diverse set of American families to paint a portrait of the pandemic’s impact on kids and the people who take care of them. Like a birth story, our individual experiences of that time have similar plot points — mask mandates, schools closing, vaccines for adults and then, much later, for our kids — but the details for each family are unique and indelible. Even glancing at my daughter’s art supplies now pulls me back to gluey fingers scratching at marker stains the floor, episodes of DrawTogether With Wendy Mac on my phone propped up by a half-full glass of juice, our preschool’s one precious hour of online sing-alongs, tantrums from my then-4-year-old begging to see just one friend, Mama, please.

As she searches for answers for all of us, Kamenetz finds that critical to any big American question is the history of our social structures, in this case programs like foster care, subsidized school lunches, and special education. It may come as no surprise to parents that Kamenetz concludes we have a long way to go toward valuing families and children enough to offer the support necessary to thrive — or at least to bring us on par with other developed nations. Romper spoke with Kamenetz on Zoom from her home with her kids, appropriately, in a nearby room.

Reading this book was a real trip. It gives such rich context on the pandemic, but at times it feels almost hard to read. I think I’m still working on my own personal narrative of being a parent during that time. Did you have a specific audience in mind for The Stolen Year?

I hope to reach decision-makers because now is the time to hold people accountable before things slip back into the memory hole. But I also want you and me and people who went through this to feel seen when they’re ready for that. I want that to exist. The flu pandemic was buried; people did not talk about it or want to talk about it. That obviously led to some mistakes. And even today, there’s no memorial to the victims of the Spanish flu in America. I believe in the value of stories because they keep people interested and connected, and they activate our empathy. There’s a kind of book that’s going to be written about this time through major actors on the public stage. But so much of what families went through happened privately and internally, and that’s part of history also.

You trace not only the timeline of the pandemic and the lives of individual families but also the lineage of American social constructs — the way we think of caregiving and schooling. You discuss how some of the disasters of 2020 and 2021 were tied to how our country has prioritized policing families over supporting them.

I mean, I didn’t expect this book to have a chapter about the foster care system, but it was something I kept confronting, and [it] seemed key to the question “Why don’t we prioritize children?” I thought Americans loved kids. I came to find out that we have a legacy of sentimentalizing kids — yes — but also thinking that we can “save” kids by removing them from their families and communities. That was a major aspect of chattel slavery and our history of Native American genocide. I also wrote about Orphan Trains in the 19th century, which took children of new immigrants from Europe and shipped them out to work on farms in the middle of nowhere. This fallacy that children thrive separately from their families or their communities in a meaningful way is repeated again and again. The case I make in the book is that our social welfare policy has a legacy of rich [white] ladies doing what they think is going to be best for other people’s kids. And that’s the system that we have today.

You illustrate the further erosion of so many different relationships during the pandemic — between parents and teachers, teachers and schools, government and families. How did trust play a role in the way things went down in this country?

Well, in blue states, there were loud progressive voices saying we need to open schools because kids need school. And then there were very loud progressive voices saying it’s not safe to open schools. And among those who said it wasn’t safe to open schools, there was a fair amount of people who said that because they didn’t trust the schools. The reasons they didn’t trust the schools were historic and had to do with [the government’s] divestment in schools. The story that I quote often is from Patricia in D.C., who is a special education aide and a mother of two. She knew that her own children and the children that she cared for were not benefiting from remote learning. But she said, “When I was a pre-K teacher, I saw rats in my classroom while my children were napping on their mats. And now you’re going to tell me that it’s safe to go to school in a pandemic? I don’t believe you.” That mistrust was very earned.

There was so much fear and uncertainty that as things dragged on, more and more people pointed to [the deaths and cases] and said, “It’s one thing if I’m making my kid stay home from school and people’s lives are being saved. But the U.S. has lost more people than any other rich country.” People don’t trust the public health restrictions, so they don’t follow the public health restrictions, and then public health restrictions aren’t working. That’s the spiral we got into.

The title of the book is The Stolen Year, but you write about so many other pieces besides time that have been lost and may be hard to rebuild. What comes next?

I delayed submitting the manuscript because I was really hoping that some piece of Build Back Better was going to get passed with respect to families and children. So it’s very sad to see that whole package be passed by the House and then just get buried again. I don’t think we’re there yet. Now I’m worried about Democrats losing the House and all of that getting taken off the table for a generation.

There’s reason to hope that this school year is a path of recovery that the past school year was not, but it is a very acrimonious path. We’re having a lot of finger-pointing, and school systems are really on their back foot because they have lost students. A lot of parents have left the public schools, and there are more that are leaving, so that’s a really big challenge. Parents have lost confidence in Democrats, but they still think that their teachers are doing the best they can.

At our public school, enrollment is down so much that they’ve cut one of the kindergarten classes. It feels like a long road back. As parents and as community members, what lessons do you hope we take away from this time?

Everyone who took care of children during this time should feel very proud of themselves.

The most positive difference that I’ve seen amongst almost everyone I spend time with is increased vulnerability and willingness to share things that are personally difficult. The pandemic really lifted the stigma for a lot of people in talking about mental health. It was impossible to pretend that things were OK. Ultimately, vulnerability helps us connect, and it’s going to help us rebuild trust. I see that happening, and I think it’s very positive.

As we move forward, have you seen any potential for reframing the social constructs we’ve inherited that have been failing us?

I’m seeing a lot of reconsideration of the relationships people have to each other, and also on a social level. You can think about the mutual aid networks that sprang up, and the new level of civic involvement. Three months into this pandemic, the United States engaged in the largest protest movement in our history — the largest protest movement in the globe’s history as far as we can document. That’s a pretty profound reaction to this sense of being disconnected and polarized.

Social movements take a lot of time and go through different stages. The labor organizing right now is quite impressive, and likely to be more and more significant. As I mark out in the book, we have lacked a mainstream, strong feminism in this country that is intersectional, cross-class, and takes on the caregiving agenda as strongly as it does women’s right to be in the paid workforce. I don’t think that happens overnight, but the recognition is there that it needs to happen. But I don’t know who the leaders are of this change. Maybe they’re on TikTok right now.

The Stolen Year: How Covid Changed Children’s Lives, and Where We Go Now is available now.

Rebecca Ackermann is a writer, designer and artist living in San Francisco. Her essays have been published by MIT Tech Review, Electric Lit, and The New York Times, among other outlets. Her short fiction has appeared in Wigleaf, Barren Magazine, Flash Frog, and elsewhere. You can find her tweeting bad jokes and strong opinions @rebackermann, and constantly redesigning her website, rebeccaackermann.com/writing.