BOOKS

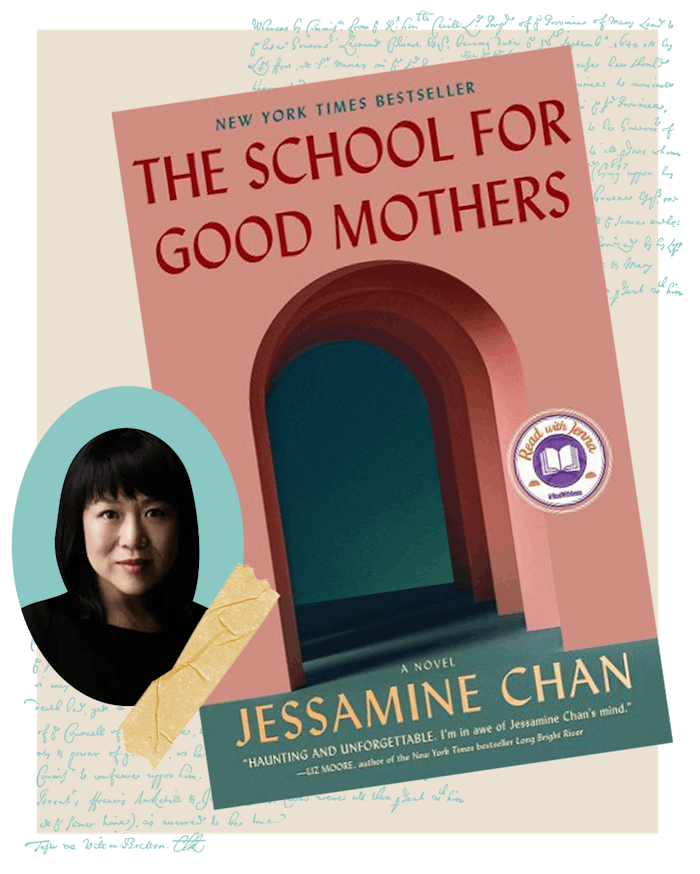

At The School For Good Mothers, The Call Is Coming From Inside The House

Jessamine Chan’s disturbingly prescient new novel is both dystopian and deeply real.

Recently, I found myself in a parenting dilemma. After my morning “workout” of wrestling my wet-noodle-limbed toddler into the required sweatshirt, sweatpants, snow pants, coat, hat, mittens, and mask, we headed out to meet her cousins for sledding. On the way, I stopped for gas. From the backseat, my toddler declared she absolutely had to have a snack.

I froze with indecision. Leave her in the car for the five minutes it would take to run in and grab a bag of pretzels? Or extend the task by bringing her with me, with all the unbuckling, carrying, and arguing that would inevitably ensue?

My mind raced, calibrating the choices: I had memories of being left in the car as a child while my own mom ran into a store. I would be able to see my daughter the entire time through the glass front of the gas station. It would be quick. And on the other side: I remembered articles about mothers charged with crimes for the exact thing I was contemplating.

I stood, paralyzed by the decision, wondering to myself: What choice would a good mother make?

This is also the question at the center of Jessamine Chan’s disturbingly prescient new novel, The School for Good Mothers. Published in January this year but set in the not-too-distant future, Chan creates an alarmingly-plausible world in which mothers deemed unacceptable by the state can have their children forcibly removed while they attend a mandated re-education program whose curriculum is designed to make them into “good mothers.” Failure to complete the program to the standards set terminates the mothers’ parental rights (permanently) and lands them on a public registry of “bad mothers.”

The story focuses on Frida, who, in her own words, had “one bad day.” Freshly divorced and still adjusting to single parenting, Frida, after a week of sleepless nights thanks to an ear infection and a boss who is unsympathetic to any child care-related troubles, leaves her toddler daughter, Harriet, alone. Initially, Frida plans to only be gone for a short time, just enough to grab a needed work file, but she slips, the dizzying relief of freedom from the demands of childrearing almost intoxicating her. Before she knows it, Frida has let hours slip by. When she returns, she is plunged into a nightmare: her daughter taken by authorities after a neighbor called in the girl’s crying; Harriet’s removal; court; her mandated year away at the new program.

As I read, I couldn’t help but think about all the opinions I was inundated with on a daily basis, all the internalized impossible standards I was being held to right now.

Though the school is filled with some near-future AI that doesn't quite exist yet — the “bad” mothers practice their parenting skills on incredibly lifelike robotic dolls, for instance — Chan mostly grounds the mothers’ experiences in current technology. From wearable smart socks that compile baby’s bodily data to companies that provide parenting instructions through a series of webcams set up in the home, the America of right now already has a host of technological devices primed and ready to help parents choose the “best” for their child.

The problem, Chan seems to want us to understand, lies in the uneven privilege of these things: affluent parents ready and eager to pay a pretty penny for this type of surveillance, while low-income parents are already living a reality in which they are more likely to be subjected to things like mandated parenting sessions. It’s not a far leap to assume the tech that affluent moms will jump to embrace could be used as a cudgel against low-income mothers, single mothers, and mothers of color. The success in The School for Good Mothers echos the success of feminist dystopian novels before it — how Red Clocks teased out the repercussions of the already proposed Personhood Amendments or how Vox made good on the disturbing trend of duct-taping wives’ and daughters’ mouths for Christmas cards or how, most famously, The Handmaid’s Tale looked not forward but back into history for the chilling subservience imposed upon women — showing us that the truly terrifying things about the future are usually the ones we are already living with.

It would have been easy for Chan to stop there, her bestseller debuting at a time when it seemed like all things motherhood were being evaluated and reevaluated, Covid-19 exposing just how threadbare our semblance of safety netting for parents truly is. But Chan goes deeper. Underneath the dystopian plot lies an almost more sinister twist on motherly expectations. Reading the novel, I was struck by the uncanny similarities between the messages the instructors in the school parrot and the messages I’ve been continuously bombarded with since having my first daughter four years ago.

There are just so many ways right now to fail at motherhood. And so many constant reminders that you are.

Mothers have always been subjected to certain childrearing expectations (“Put some socks on that baby!”) but the demands on how to be a “good” mother have grown exponentially over the years, particularly with the rise of social media. Suddenly it wasn’t your overbearing mother-in-law or the busybody neighbor judging your performance as a mother, but a slew of pseudo-expert influencers setting a new ideal to live up to. The mommy-bloggers of the early- and mid-‘00s quickly gave way to polished and posed Instagram accounts (with pithy letterboard comments to keep it “real”). And many creators began to see success with tailored content for all the impossible tasks of early motherhood, influencers who promised they could help your baby sleep, help your baby eat, and provide the best, most stimulating ways to play with your baby.

As connected as these internet-based communities can make new moms feel, the underside is obvious: There are just so many ways right now to fail at motherhood. And so many constant reminders that you are. It's not just breast milk or formula, it's breast milk or organic formula. It's not just stay-at-home or day care, it's stay-at-home or Montessori or Waldorf or Reggio-inspired day care programs. This idea, just how many choices are available to be right and wrong about, is borderline parodied in The School for Good Mothers. Frida and the others are trained in how to recognize and deliver specific types of hugs in different situations; according to the school, you can even be wrong in hugging your child. It’s a scary encapsulation of what constitutes correct mothering, a supposed terrifying prophecy for the future, but as I read, I couldn’t help but think about all the opinions I was inundated with on a daily basis, all the internalized impossible standards I was being held to right now.

But the most interesting part about Chan’s dissection of “good mothering” is Frida herself. It would have been tempting (and easy) to create a protagonist who is essentially blameless in her slip. What mother hasn’t given in and chosen the easy way against her better knowledge: A puffer jacket in the car seat? Extra hours of screen time? My own fleeting thought to leave my 3-year-old in the car. But, Frida did not slip. Frida left her very young child alone in a house for hours, and as much as we can empathize and understand how and why it happened, there is a prickling of suspicion, whiffs of judgment. Chan forces us into a kind of mental gymnastics with regard to Frida — we both see and understand her even as we judge; just like Frida in the school sees and understands the other mothers while trying to distance herself from them, separating her own “bad day” from the supposedly worse moms who have yelled or hit or truly abandoned. It makes the reader pause, consider their own initial judgments of Frida (“I would never do that”) echoed in Frida’s judgments of others, making one inevitably wonder, if I’m thinking that about someone else, who is thinking that about me? And even outside the crucible of the school, we see these judgments from Frida: multiple references to the supposed benefits of breastfeeding over formula, a refusal to use day care, the choice of clothing for toddlers.

We can pretend we are making our own choices as mothers, but it’s never true because our choices do not exist in a vacuum.

These judgemental asides are inconsequential to the overall plot, but vital to what Chan is trying to say; they capture the way that our individual choices impact collective thinking about good or proper motherly behavior and vice-versa: judgments sent outward that come back internalized, self-inflicted. We can pretend we are making our own choices as mothers, but it’s never true because our choices do not exist in a vacuum. As Leslie Jamison wrote in her personal history of C-sections: “Motherhood is instinctual, but it’s also inherited: a set of circulating ideals we encounter and absorb.”

These circulating ideals are what I found myself paralyzed by on that frigid January day. My choice was not about the situation in front of me, but rather all that I’d ever seen, heard, read, and learned about motherhood. My choice was not my choice in the present but a choice of all the beliefs of good motherhood. There was the (rightful) fear of someone possibly reporting me for “abandonment” but there was also my own worry about what was correct, what I should do.

It’s this duality that makes The School for Good Mothers most unnerving. Because as Chan shows us, when it comes to expectations in motherhood, the call is, just as often, coming from inside the house.

Elizabeth Skoski is a freelance writer based in New York. Her writing has appeared in The Washington Post’s “Answer Sheet,” Huffington Post, Bustle, and others. Follow her on Twitter @lizskoski.