Love & Grief

A Weirdly Hilarious Book About Losing A Best Friend

Catherine Newman’s debut novel breaks your heart open while you laugh in wonder.

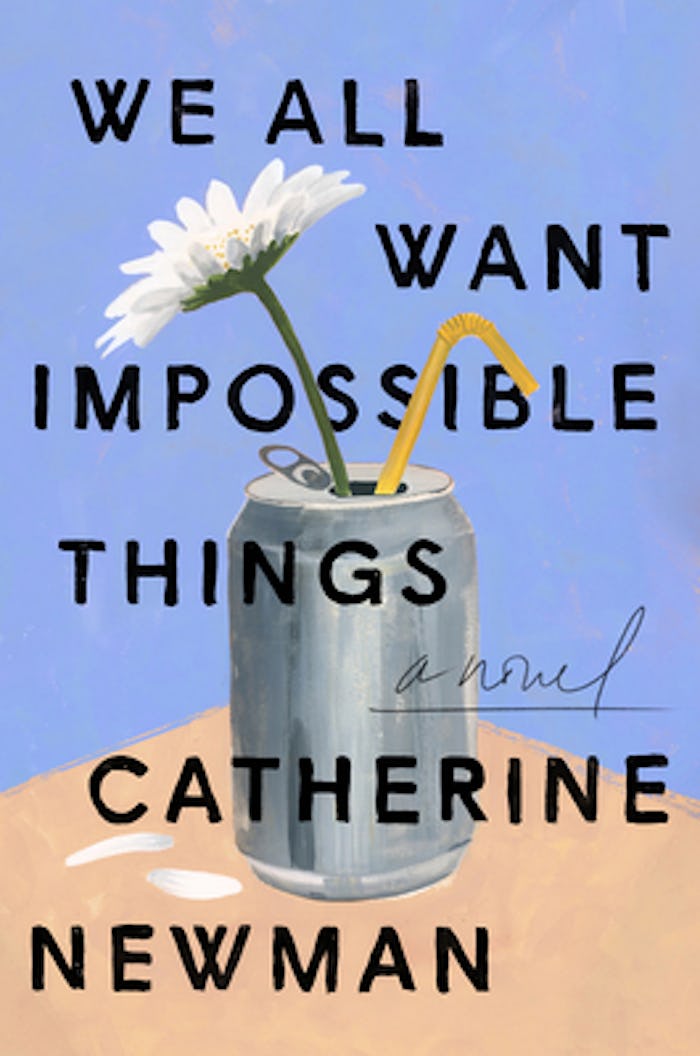

We All Want Impossible Things could be described as a book about cancer or a book about grief, but I’d describe Catherine Newman’s debut novel as a love letter to best-friendship. Inspired by Newman’s personal experience, We All Want Impossible Things tells the story of Ash, a woman whose lifelong friend Edi (who, Ash tells us on the first page, “is so gorgeous I could bite her face”) has come to a hospice near Ash’s home in order to do what one does at a hospice — that is, unfathomably, to die.

It sounds like an unbearable premise. And, indeed, it is. But while Newman is not afraid to take us — and herself — right up to the hardest, most raw and unendurable faces of loss, she is also not afraid to show us the light, the exquisite beauty, and weird, lifesaving hilarity of the same. And that is what makes this story not only bearable, but affirming, entertaining, and unaccountably, wonderfully funny.

In one early scene, a hospice volunteer (an incongruously hot younger man named Cedar) steps into Edi’s room and interrupts Ash squatting over Edi in bed, a headlamp on her forehead, plucking out her chin hairs.

My copy of the book has a heart scrawled in this spot, where I had a sudden and vivid vision of my own best friend doing this for me one day or vice versa. Is there anyone more beloved than the friend of so many years, the keeper of so many of your memories, the person you know would pluck out your chin hairs in a hospice?

“My heart fills with, and releases, grief in time to my breathing,” Ash tells us as she sits at Edi’s bedside while Cedar plays “Across The Universe” on his guitar, and I feel my own bone-deep grief sense memory responding in tune.

I have been a fan of Newman’s writing for years. I started reading her delightful parenting and food blog, Ben & Birdy, years ago, when our now college girls were round-faced preschoolers. She and I eventually became Facebook friends, and we have worked together on pieces for Romper, so I already knew what an incredible writer she was, the kind whose essays I send, over and over, to friends who will also just get it. What I discovered in this novel is that she has a deep talent for the macabre humor and absurdity that it takes to describe the loss of someone you cannot bear to lose. (There is also, much to my delighted surprise, quite a bit of sex in the book.)

On more than one occasion, I found myself crying and then immediately laughing out loud. “Oh, my god, Mom, could you be any grosser?” says Ash’s younger daughter Belle upon finding her in bed with a man. “No offense,” Belle quickly tells the man, who takes none. “Don’t slut shame me,” Ash says, and Belle laughs and says “Fair,” and hands her mom a permission slip to sign. “I sit up carefully, keeping the sheet wound around my tragic boobs so as not to depress her further.”

The hospice, which Ash describes as a “haunted B and B,” had estimated, when they checked Edi in, that she would be its “guest” for just a week or two. “‘We don’t think of this as a place where people come to die,’ the gravely cheerful intake counselor had said to us,” Ash recounts. “‘We think of it as a place where people come to live!’ ‘To live dyingly,’ Edi had whispered to me, and I’d laughed.”

‘And so we held her quietly. We held her while the biggest loss of her life — which was bigger than the loss of her actual life — sank into her like mercury.’

Like real life and real grief, the book is about many things simultaneously: it’s about being a woman of a “certain age”; it’s about complicated relationships (when we meet Ash, she and her husband, Honey, are separated, allowing for several sticky affairs to unfold gratifyingly in the midst of everything); it’s about motherhood — Ash has two deliciously drawn daughters, one away at college and one about to be, and Edi, to our repeated devastation, has a 7-year-old son named Dash, to whom she has to do the thing that is impossible: leave him forever.

“And so we held her quietly,” Newman writes of the moment when Edi decides it is best for Dash to stay home in Brooklyn and miss the trauma of watching his mama die of ovarian cancer. “We held her while the biggest loss of her life — which was bigger than the loss of her actual life — sank into her like mercury.”

Tweezers — and deep, abiding love for her friend — aside, Ash is no saint tenderly administering virtuous care. She freely divulges her neuroses, her jealousies (at one point Ash tells us that Edi’s dresser in the hospice has two framed photos of the two of them, and one of Edi’s “other” best friend, the impossibly cool Alice; elsewhere, Newman captures deftly the loving but not-quite-kidding rivalry Ash feels with Edi’s husband, in her lifelong quest to be Edi’s Person), and her insecurities. She, like us all, is messy, she craves attention —“Can you please not try to make everyone at my funeral fall in love with you,” Edi asks her at one point, “not laughing” — she makes selfish choices and falls apart while holding everything together. And of course, that’s what makes us love her, and love her story, and love the dear friend she is losing.

“Why do we even do this — love anybody?” Ash asks us. “Our dumb animal hearts.”

I was afraid Newman’s book would break my heart, and I was right. But it was a good break — the kind of break that breaks you open. And it also made me laugh (and sometimes, laugh-sob). The thing is — life is at times completely, utterly unbearable. It is just absolutely not endurable. Who thought this up? “Why do we even do this — love anybody?” Ash asks us. “Our dumb animal hearts.”

And yet, we bear it, we endure. Like Edi, we might find ourselves smothering our daughter with love as she makes one of her trademark salads (“sturdy, difficult vegetables lined up on the cutting board”); or suddenly noticing, in the middle of a profoundly moving moment filled with love and grace, that our dying friend’s nail polish is peeling. Like Edi, we might wander outside after a day that lasted a year and see the stars are shining in the winter sky, and there’s a crescent moon, and owls are hooting to each other, and our sort of ex-husband has shoveled the driveway, and we might, overcome, suddenly realize we are lying down in the snow.

We bear it, we endure. What other choice do we have? And hopefully in the darkest, most wretched, unacceptable moments we are able, as Ash and Edi have been, to grasp how impossibly lucky we are.

We All Want Impossible Things is out now, wherever books are sold and at your local library.

This article was originally published on