Life

Calvin And Hobbes Taught Me Everything I Need To Know About Feminism

Reading a book 200 times is a surefire way to find out whether you love it or want to throw its rhyming llama couplets into the diaper pail. Children's books especially do a tricky dance for an audience of squinty-eyed parents and wide-eyed tots: the best ones, like a syringe of infant-suspension Tylenol, have a little something for the parent at the end. These are the ones we are celebrating in This Book Belongs To — the books that send us back to the days of our own footed pajamas, and make us feel only half-exhausted when our tiny overlords ask to read them one more time.

I grew up with a house full of books to read, lots of books perfect for a little girl. But like every other younger sibling on the planet, I wanted what my older brother had instead. While I have lovely memories of books given to me, it’s the Calvin and Hobbes’ books — it seemed like my brother had a new one under the tree every single Christmas during the late 1980s and early 1990s — that I remember most fondly.

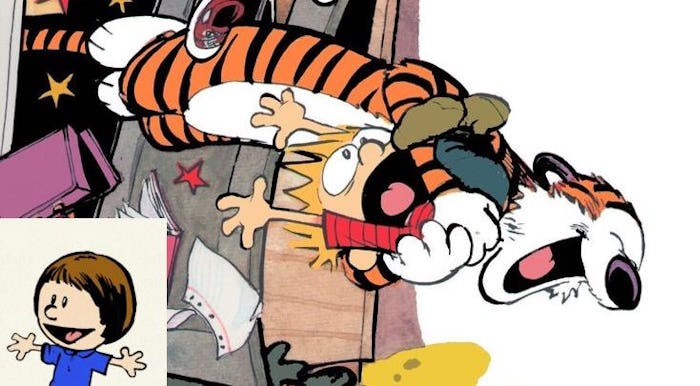

If you’re not familiar with the comic strip, it’s about a little boy named Calvin and his overactive imagination that sees his stuffed tiger Hobbes come alive and join him on adventures. I read every single one of the Calvin and Hobbes books with the relish of a younger sister who’s not supposed to be touching her older brother’s stuff. Little did I know these books would inadvertently become fuel for the feminist pyre years later.

Calvin’s exploits made me giggle, of course, and I especially loved Hobbes. As a kid with a big imagination, Calvin’s camaraderie with his stuffed tiger really struck a note. Like Calvin, I had a stuffed animal as an imaginary friend: I pretended my teddy bear Gregory was my (imaginary) husband and father to our (imaginary) children, fellow stuffed animals. As I got to be 10 or so — those important years when you have to distinguish yourself as Not A Kid Anymore — I sensed that it was childish to play with stuffed animals. Still, I reasoned, it must be OK because Calvin tooled around with a stuffed animal and he was cool.

Calvin let me give myself permission to play with stuffed animals, but that was where the similarities ended. He hated school, cheated on tests, and made up bogus facts for class presentations. He hammered nails into his parents’ coffee table. He tromped mud through their house. And when he wasn’t terrorizing his long-suffering parents, his teacher Miss Wormwood, or his babysitter Roz, he was being mean to a little girl in his neighborhood, Susie Derkins.

Susie Derkins. Even her name sounds dorky, and that’s what Susie was: a good student, a well-behaved child, and bent on squashing Calvin’s fun by following rules and being respectful to adults.

I liked any strip in which Susie appeared because not only was she a girl, like me, but she was a girl like me: a smart, principled do-gooder who tattle-tailed on Calvin because she found his behavior destructive, gross and offensive. As the strip is told mainly through Calvin’s eyes, Susie is a pushy, bossy, annoying nag — mostly drawn with her brows furrowed, mouth wide open in a scold.

Calvin continually pelts Susie with snowballs. In one strip, he sends her a 'hate-mail Valentine' with dead flowers.

Despite using Susie — asking to cheat off her tests, calling her up to ask for homework assignments — Calvin made no attempt to hide his contempt for her. And it wasn’t just on account of her being a star student. It was because she was an intelligent, rule-abiding girl.

Calvin goes off his rocker when he discovers Hobbes hanging out at Susie’s house for a tea party — betrayed by his own imagination! He storms away from Susie and her stuffed rabbit after playing “house,” even as she calls after him, “I don’t see why you’ll play pretend with your dumb ol’ tiger but not Mr. Bun.” His disdain for women and girls in general, and Susie’s gendered play in particular, is made clear.

It’s all exactly the kind of mean behavior that in 2017 we would call “bullying” ... but in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, everyone just said this is what boys did when they liked you.

So he is pretty mean to her. Calvin continually pelts Susie with snowballs. In one strip, he sends her a “hate-mail Valentine” with dead flowers. He tells her that his tree house is “no girls allowed.” He calls her “fat.” It’s all exactly the kind of mean behavior that in 2017 we would call “bullying” (or, you know, “the 2016 presidential campaign”). But in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, everyone just said this is what boys did when they liked you. And so us girls put up with it.

The joy of reading Calvin and Hobbes is that you pick up more from the strips as years go by. (This phenomenon is lovingly addressed in the documentary about the strip, “Dear Mr. Watterson.”) Reading the books over and over again at my parents’ house over the years, I began to see how deftly Watterson drew the Calvin and Susie relationship. While I can’t speak for Watterson’s intentions, it’s clear to me as a reader that what each character represents about human nature was a lot more nuanced than I picked up on as a kid.

Child-me read Susie as the lame, annoying girl antagonist, because that’s how Calvin saw her. Whether she was raising her hand with the correct answer in class or inviting Hobbes to a tea party (a mortal insult), Susie existed to throw a wet blanket on everything for Calvin and suffer the consequences for it. And as a girl who had Scotch tape put in her hair by a boy who sat next to me in science glass — punishment, I guess, for being a major dork — Susie was someone I grudgingly related to.

Adult-me, however, can read between the lines. Calvin might have enjoyed himself more, and his aberrant behavior is the reason the strip is so funny. But Susie was smarter, more focused, more driven, a better citizen, and clearly the one who would become successful later on in life. (When the pair get sent to the principal’s office once, Susie frets that this will go on her permanent record and make her unable to get a Master’s degree.)

Meanwhile, the disappointing boys become disappointing men.

It’s not difficult to imagine an adult Susie proudly wearing a Tina Fey and Amy Poehler-esque “Bitches Get Stuff Done” t-shirt. While it may take a few decades, this was our reward for withstanding the cruelties of childhood — the “geeks shall inherit the earth” mode of karma.

Meanwhile, the disappointing boys become disappointing men. In one comic, Calvin turns to Susie in the classroom and says, “I find my life is a lot easier, the lower I keep everyone’s expectations.” It’s funny when a little boy says that; it’s profoundly sad when you know adult men who also think that way. It is also not difficult to imagine that Calvin ends up one of the poor saps struggling to keep up with their wives and girlfriends, personally and professionally, in Hanna Rosin’s book The End Of Men: And The Rise Of Women. Alas, in adulthood, the Susies of the world don’t want the Calvins. In fact, we realize we’re better off without them.

Adult-me is still a Susie Derkins: intelligent and driven and still massively uncool, but successful enough to not care so much. As an feminist writer, I’ve gotten plenty of my own “hate mail Valentines” — mean-spirited letters from men, sometimes with pictures of penises attached. When experience that never becomes normal or acceptable, it’s easier to deal with after a childhood of having tape put in my hair in class. You come to realize it’s just the immature behavior Calvins of the world, still doing what they do best.

The strength and self-determination Susie showed and her refusal to cow to a bullying little boy have stayed with me in adulthood. Just as she got pelted with snowballs by Calvin, I’ve developed a thick skin for those same snowballs from male colleagues and bosses. While the situation has changed — now the problem is workplace sexism, not classroom bullies — that feeling of “ew, a girl” is the same.

Like Susie, it's not something I will put up with. And like Susie, I’m unafraid to lob those snowballs back.