News

Can States Ban The Abortion Pill? FDA Rules May Make That Hard

Medication abortion poses questions in the absence of Roe v. Wade.

On June 24, the Supreme Court ruled that abortion rights were no longer subject to federal protection, prompting 10 states to effectively ban abortions within a day of the ruling, leaving untold numbers of pregnant (or potentially pregnant) people without immediate access to the kind of health care they were planning for or might need. Some have begun to consider alternatives to surgical abortion, especially in light of the rise of telemedicine and greater federal accessibility to abortifacient. But can states ban the abortion pill now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned? Here’s what we know so far.

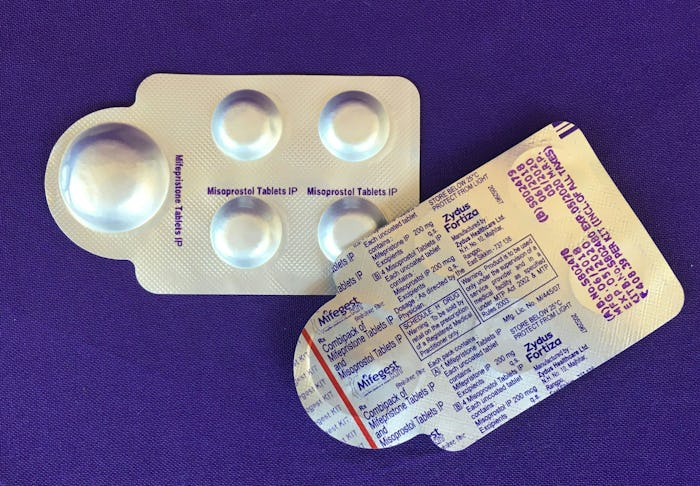

“Abortion pills” are two different medications.

A medication abortion is typically done through the use of two pills: mifepristone, sold as Mifeprex, and misoprostol. First, a patient takes Mifeprex by mouth. Then, within 24 to 48 hours after taking Mifeprex, they will take misoprostol buccally (in the cheek pouch). Mifepristone works by blocking the hormone progesterone, which results in the breakdown of uterine lining, ending a pregnancy. Misoprostol, the second medication, also sold as Cytotec, is taken up to 48 hours later and causes the uterus to empty. According to Planned Parenthood, they are most effective when taken within the first eight weeks of pregnancy (up to 98% effective) but remain up to 87% effective when taken up to 11 weeks. (The World Health Organization says they could be used through the first trimester.)

Misoprostol is often prescribed off-label in cases of spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) to help the body expel uterine contents and thereby avoid more invasive surgical procedures such as dilation and curettage (often called D&C) and as a way to induce labor in patients ready to give birth though such use is not approved by the FDA.

More than half of all abortions in the United States are medication abortions, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Mifepristone became more widely available in December 2021.

Approved in 2000, mifepristone has an excellent safety record. Abortion rights advocates have suggested that mifepristone has been subjected to unnecessary regulations over the years — despite its safety and ease of use. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, prescriptions for mifepristone required an in-person appointment for prescription and dispensation ie, it had to be taken at a medical facility. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) eased those restrictions during the pandemic and, in December 2021, permanently did away with the in-person dispensation requirement. This allowed patients to utilize telehealth options and receive pills by mail, expanding access considerably.

Medication abortion is banned in many states, but the Biden Administration is challenging those bans.

In many states, abortion pills are either literally or effectively banned, including 19 states that require the clinician providing a medication abortion to be physically present when the medication is administered. Under these statues, telemedicine is not an option, and neither is receiving these pills by mail. Eight states immediately banned all forms of abortion in their state, including medication abortion after the SCOTUS ruling. At least six states have explicitly banned abortion pills via telehealth with additional states poised to follow suit. On Sunday, South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem announced she would put forth legislation to ban telehealth medical abortion.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, while not outright banning the use of mifepristone, 32 states make access more difficult by requiring physicians alone to administer the drug.

But abortion rights activists, and the Biden Administration, are seeking to find ways around these restrictive laws.

The New York Times reports that mobile clinics are establishing themselves in states where abortion pills could be easily obtained via telemedicine and mail... right on the borders of states where it is illegal. A patient would still have to travel potentially long distances for health care, but less far. “By operating on state borders, we will reduce travel burdens for patients in states with bans or severe limits,” Dr. Julie Amaon, medical director of Just the Pill explained to the Times. “And by moving beyond a traditional brick-and-mortar clinic, our mobile clinics can quickly adapt to the courts, state legislatures, and the markets, going wherever the need is.”

Attorney General Merrick Garland has more directly challenged the state bans. “The FDA has approved the use of the medication Mifepristone,” he said in a statement. “States may not ban Mifepristone based on disagreement with the FDA’s expert judgment about its safety and efficacy.”

Garland hangs his argument on the idea of “federal preemption,” essentially stating that state laws unduly regulating these drugs conflict with federal law and, as such, federal law has the final say. (In regard to medication, precedent was established in 2014 when a federal judge in Massachusetts struck down a state law that would have regulated the sale of opioids more stringently than federal guidelines.)

The White House has similarly announced its intention to work with the Department of Health and Human Services to make mifepristone “as widely accessible as possible.”

Many have sought to obtain abortion pills from other countries.

While this practice is not legal, the risk of prosecution for patients and especially prescribing doctors in other countries, remains low as authorities don’t (yet) have an effective way of policing such orders. Organizations like Aid Access work with individuals to obtain prescriptions of abortion pills from European doctors via a pharmacy in India for between $55 and $150.