Call Me By Your Name

Think About Us Before You Give Your Baby A "Unique" Name

Are you planning to name your kid something “cool”? Hold up a second. I just want to talk.

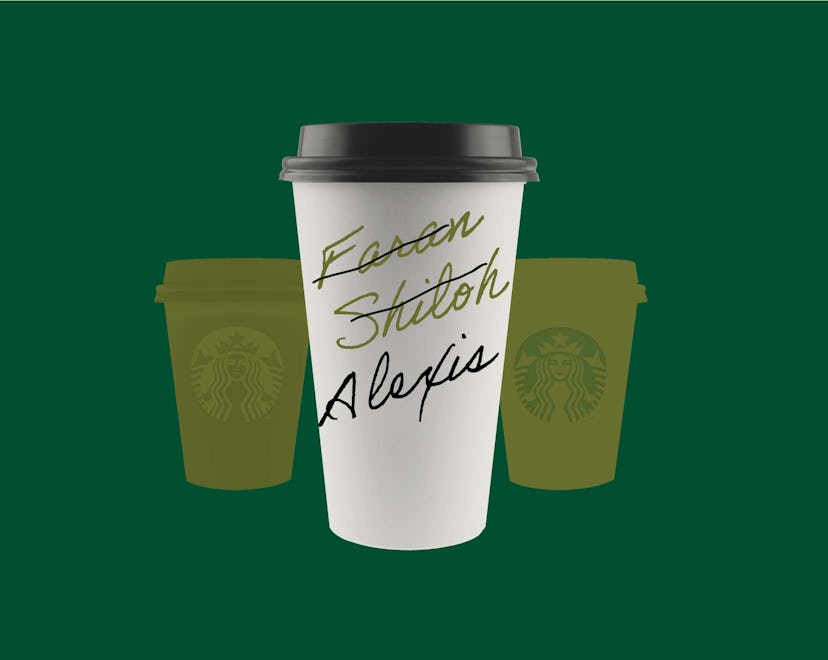

My name is Faran… but not at Starbucks.

There I’m Alexis, my middle name, because otherwise, it’s a spelling joust every time I need a cold brew. I’m not myself at hot yoga, either — I’ve been “FK” since my very first vinyasa — or at my local Thai place, where my pickup order is always for “Frank.” For years, my birth control prescription read Karan. “She seems cool,” I would think while staring at a pill pack with a name that wasn’t mine. “I hope that girl Karan is having a great day, or at least really epic sex.”

Such is the plight of having an “unusual” name, one that’s defined by the Linguistic Society of America as being a name shared by less than .01% of our national population. “We wanted a name that was beautiful and stood out,” says my mom when I ask about her choice. As is tradition in my parents’ culture, they wanted to honor one of my ancestors — my dad’s grandmother from Soviet Russia named Freyda. After debating “Farah” and “Franny,” they finally saw my future first name as a stranger’s last name in a newspaper article, and voila. Here she is, world: Faran. “I never thought your name was all that weird, though!” insists my mom. “Just cool. Unique.”

But a “unique” name is a complicated gift, especially for a child. It makes you memorable — maybe even cooler, as my parents believed. In many cases, it honors a family or cultural history, and ties you to a world way beyond your backyard. Unique names can also lead to chaotic misspellings in legal documents and plane tickets. (As my friend Jenya, 44, says: “You know how TSA says, ‘Show up for your flight an hour early’? If you have a weird name, make it two hours. And never let someone else, like a travel agent, spell your name for the ticket.”)

“People use my name as an invitation to guess what I ‘am’ as if it’s a game.”

I spoke with nearly three dozen “uniquely named” people for this story, from Ariyas to Zooeys. Some of us carry names carved into our families’ cultural touchstones; some of us were raised by hippies or Hollywood moguls determined to shine a spotlight onto our lives from birth. Thanks to immigration status, ethnicity, or race, some of our families are already “othered” in the double-edged mosaic of American life, which cuts deep in its attempts to keep so many on the shallow end of the resources pool. But every single person I spoke with — every single one! — said that as adults, they’re happy with their first names.

And also? There are some things you should know if you want to name your child something less typical than Olivia or Jackson.

First, everyone will ask your child/teenager/adult about their name. Some of these questions will be good-natured, curious, and welcome. Others will be icky, eliciting unwelcome personal info about one’s ethnicity. “People use my name as an invitation to guess what I ‘am’ as if it’s a game,” sighs Shiloh, 35, a business development executive with “exotic” curly hair and huge eyes that propelled her former career as a child model. “But look, my name is from the Neil Diamond song. It’s just an oldies station staple, not a window into my family history.” She told me this as she sipped on a green juice labeled “Shayla.” (“I also get Sharon a lot,” she laughed.) My friend Rawdah, 30, is a model from Somalia who grew up in Norway. Her name is "not common, either in Norway or Somalia" she told me cheerfully when we first met — “but everyone tries to pretend they know what it means!”

American first names adhered tightly to convention until the ‘70s, when a wave of immigration coincided with the countercultural revolution and the Black Power movement, widening our nation’s thorny paths to success and community. By the 1980s, names rooted in African American and Hispanic culture (like Latoya and Alejandro) were among the most popular, along with more “traditional” fare like Emily — or, as the New York Times recently put it, the “little black dress [of names]… that never truly goes out of style.”

Today, data scientists seem obsessed with figuring out if our unique names will help or hurt us. According to research, having a weird name actually boosts our chance of gaining promotions and friends, but it can also penalize us at work and on dating apps. That’s true even with A-list celebs naming their kids as if they’re Hunger Games heroes. (You can’t tell me Psalm Kardashian West and Lyra Antarctica Sheeran aren’t plotting a revolution with Katniss Everdeen. You just can’t.)

“Growing up, I would brace myself for people trying to say my name,” says Tchesmeni, 33, who was named for an Ancient Egyptian word. (“To my knowledge, we are not ethnically Egyptian,” says the Brooklyn native.) “The doctor’s office, the first day of school, anytime we had a substitute teacher — I could just hear all the kids giggling and I felt a tightness in my chest. It made me really mad [at my parents] — like, ‘Why did you do this to me?!’… I used to tell people my name was ‘Tiffany’ instead.”

“I think it’s quite cool and fun — but I have a child of my own now, and I gave them a much more typical name. I just couldn’t imagine them going through years of misspellings and explanations, like I did.”

I’ve heard similar stories from Kristom (42), Silver (45), and Alaya (26). In fact, the same pattern emerged with nearly everyone I interviewed for this article: As small children, our odd names made no difference. By elementary school it was a different story, with the first day of classes being particularly fraught. (In seventh grade, one administrator accused me of inventing my name to avoid getting written up for lateness, a scenario that several others echoed.) Of course, junior high is a nightmare for Jennifers and Julyssas alike. By high school, we all grew to accept, or even embrace, our first names.

When I tracked down two other women named Faran for this piece, they expressed both love and exhaustion with their names. In the words of Faran Fronczak, 39, a news anchor in Washington, D.C., “I was a dancer and now I work in TV. When I walk into the room, I already know they won’t confuse my name with someone else’s. That’s a huge advantage, and I really do love it.” Adds Faran Efromovich, 36, a media buyer in New York City: “I think it’s quite cool and fun — but I have a child of my own now, and I gave them a much more typical name. I just couldn’t imagine them going through years of misspellings and explanations, like I did.”

But if you’re already set on calling your child something unique, here are some tips gathered from those of us on the frontlines of “Wait, what’s your name?” territory. (Real talk: I thought about asking a therapist for their advice here, but all the available experts I could find were named “Julie” or “Gregory,” and I just couldn’t deal with that.)

- Have a genuine purpose behind the name. If it’s rooted in a family tradition or a deeply-held meaning, it will be a lot easier for your child to embrace and explain (and whether you like it or not, their name will come with a lot of explaining) than simply, “It sounded cool.” And remember, there are many ways to make your child special, creative, and resilient, even with a more typical name. Steven Spielberg and Ava DuVernay figured it out, you know?

- If your child, however young, expresses a desire for a different name, listen. Ultimately, your kid is a full person separate from your own desires, and they deserve to live their full truth — even if that truth means they’re named Mike instead of Micah.

- Role play with your child before the first day of school. Preparing them for how to proudly say their name, especially if they’re shy around grown-ups, will help ease anxiety early.

- Even better? Call your child’s school ahead of time and ensure the teacher and administrators know your child’s preferred gender and pronunciation — and don’t let them add their own nickname out of convenience. If your school principal can say “Gyllenhaal,” they can and should say any name given to their students.

The good news? A recent poll says only 6% of Americans hate their name, with a much larger 60% really digging theirs. Many of the women polled for this article cited the poem “Give Your Daughters Difficult Names” by Warsan Shire as a kind of mantra; it also appears in the neon art installations of Marinella Senatore:

“Give your daughters difficult names.

Names that command the full use of the tongue.

My name makes you want to tell me the truth.

My name does not allow me to trust anyone

who cannot pronounce it right.”

That sentiment is echoed by Tchesmeni, who says she first began loving her unique name as a teen. “My dad would tell me, ‘Your name means power, so every time you say it, you’re giving yourself power.’ And I will say, it’s given me a lot of grace and patience, because I know it takes a minute to get it right. But asking for that respect — that’s something I’ve had to do because of my name.” Today, Tschesmeni says she loves introducing herself, and does it proudly.

“Except at Starbucks,” she says. “There, I’m still Tiffany.”

Faran Krentcil is a writer and editor who specializes in fashion, beauty, and travel. She is also a contributing editor at ELLE and has written for Harper's Bazaar, InStyle, The Wall Street Journal, Yahoo News, and the Business of Fashion. She was Nylon's first-ever digital editor-in-chief, and the founding editor of Fashionista.com. You can follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

This article was originally published on