Who Do You Trust?

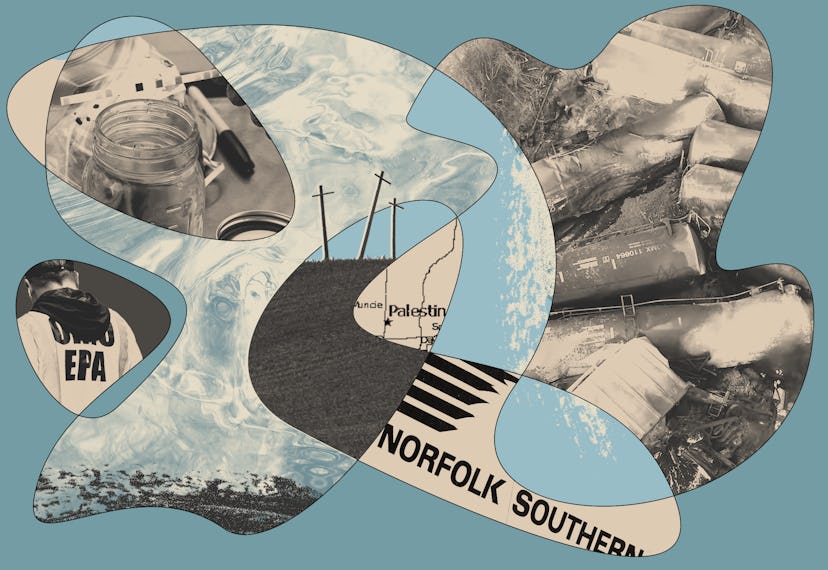

East Palestine Parents Are Looking For Answers — They’re Finding Misinformation

As they try to keep their kids safe in a vacuum of trust, desperate Ohio parents turn to Facebook groups and TikToks.

Rachel Wagoner and her family live in Darlington Township, Pennsylvania, 3 miles from the site of the train derailment on Feb. 3 that spilled volatile chemicals into the Ohio countryside. Their family farm was just far enough out of town that they did not officially have to evacuate, but Wagoner still felt anxious. She wasn’t panicked, though. This area has been ravaged by environmental blights from asbestos to coal mining to fracking for generations, so the current disaster just added to the list of things Wagoner has to worry about.

“That’s how everything is around here. I love living here. I grew up in a coal village and married a guy from over the hill. You grow up thinking these destructive industries are normal and the price we pay for progress. As a resident, you’re just on the bottom.” She says that feeling as if they are on the bottom is why many locals feel they can’t trust official sources right now. “Now, they aren’t looking to sources; they are looking to each other for information.”

A month after the accident in East Palestine, a sleepy, Midwestern town of less than 5,000, the (literal) smoke may have cleared, but many local families are in the same position as the Wagoners: They have more questions than answers and no clear place to turn. Residents and crews involved in the cleanup are reporting alarming symptoms, but Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Bruce Vanderhoff said last Wednesday that while health concerns are being taken seriously, he feels confident that the air and water in the town are safe.

Public meetings about the disaster have been fraught and tense. In mid-February, reps from Norfolk Southern, the massive rail enterprise responsible for the derailment, refused to show up to a town hall, citing “physical threats” to its employees. At the time, the town’s mayor, Trent Conaway, told local outlet WKBN, “The railroad did us wrong. So far, they’ve worked with us, and they’re fixing it. But if that stops, I will guarantee you, I will be the first one in line to fight them.” (This week, he did not respond to a request for comment from Romper.)

An avalanche of national attention doesn’t appear to be helping. Former president Donald Trump and U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg have both visited, the former to hand out Trump-branded water bottles and assure residents they are “not forgotten,” the latter to meet with local officials and call on lawmakers and the rail industry to work together to prevent further incidents. There are calls for Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine to resign over his handling of the situation, alongside criticism of President Joe Biden over his failure to visit the town yet.

As a local reporter for Farm and Dairy, an agricultural newspaper for farmers in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and bordering states, Wagoner has experience with fact-checking and finding reliable sources. She says many local residents are less sure, though. “That’s why I am on Twitter fighting a losing battle of trying to get good information out there,” she says. She’s reporting on it herself as she tries to combat misinformation in the agricultural community. “Chickens aren’t very hardy,” she says. “If someone found their chickens dead 15 miles from East Palestine but mine are just fine… I hate to doubt anyone’s lived experience, but there’s also a highly contagious avian influenza in the area.”

It’s not that Wagoner is unconcerned about the crash. The environmental impacts could last for years, she says. Wagoner just wants to make sure people are concerned about the right things instead of giving in to rumors and panic.

Photos of locals using swimming pool testing kits on their drinking water are more likely to go viral than reported news articles.

Trying to find accurate information in an environmental disaster can feel like a flashback to the exhausting and panicky early days of the pandemic, when more than half of Americans were spending two hours a day seeking out credible information. Psychotherapist Charryse Johnson, Ph.D., says this led to an “all-time low” in trust in news sources, and an increased reliance on social media, which only feeds our hunger for more and more information.

It’s tempting to trust your parenting Facebook group over a news outlet or even a government agency, says Johnson, whose work focuses on trauma, crisis management, and social justice. “In a disaster, one thing that people look for is unity, and when there’s a lack of unity, it creates a lack of trust,” she says. Throughout the pandemic, “information was constantly changing in addition to being constantly criticized.” The ensuing political division about every aspect of Covid management is rearing its head again now as citizens try to understand if they are safe or unsafe after the chemical plume.

The United for East Palestine Facebook group was launched just three days after the accident, and now has more than 7,600 members, mostly residents of East Palestine and nearby areas. People have shared links to a GoFundMe started by two parents to raise money for the East Palestine City School District (“Please don’t let this historic tragic event take away from kids just wanting to be kids,” pleads the fundraising page), or to raise funds for individual families to relocate. One resident posted about the headaches they and their cousin experienced, writing that they could also “taste the chemicals.” Another tried to start a “medical symptoms and illness registry.” Yet another compared the event to when they worked at the World Trade Center during 9/11: “The EPA at the time declared the air safe… we all know how that turned out… DEMAND answers and continued testing from everyone in the government, health experts, etc. Prayers to everyone.”

The Facebook group’s users are more likely to reference Rumble, an alternative social media service and video-sharing platform, than any accredited journalistic publication.

The Facebook group’s founder, Jenna Giannios, says she’s now hesitant to post articles in the main feed because she “doesn’t know what is true” and “It’s very apparent how everyone involved has an agenda.”

Social media’s quick and easy delivery gives us the “information” we want faster than, say, reading a scientist’s in-depth article, says Johnson. This can lead to trusting self-proclaimed experts with no actual credentials and edited images and videos being seen as fact. Over the last couple of weeks, for example, a widely circulated map shows the region of land where surface water drains into the Ohio river, not that gets drinking water from the river, as many posts have claimed, the Associated Press reports.

Photos of locals using swimming pool testing kits on their drinking water are more likely to go viral than reported news articles. When a dog died over an hour from the crash site, the owner’s post went viral because she claimed it had died from vinyl chloride poisoning. Her veterinarian turned to the local news to dispel the misinformation.

“Trusting the EPA only works if it’s not attached to a presidency.”

And the panic hasn’t remained contained to just those families living near the epicenter. Downriver, parents in cities like Cincinnati watched the updates closely, with many turning to watershed maps to try and figure out where the concerning water would head next. On Feb. 19 — over two weeks after the derailment — water companies turned off water to the city from the Ohio River, as a “precautionary measure.” Residents were assured their taps were filled with “reserve” water. The water company said it timed this decision to when derailment chemicals could conceivably impact the local supply, but the next day, water from the river was turned back on, with officials reporting that no chemicals had been detected. Many were not reassured: Why would they be turning off the water if there was no threat? How long can reserve water last, anyway? Should they head through Costco with a second cart to stock up on bottled water?

These concerns ring true for Brittany Koester, an Ohio mom living just east of Cincinnati, about 300 miles downriver of the disaster. “I don’t trust the Waterworks to have my best interest at heart. … My water supply has been contaminated by toxic chemicals before,” she says, referring to a contamination event in the ’80s at a lake where her day care would go to swim before it was shut down. “Lots of people got sick and lots got cancer,” she says. “Curious enough, I got cancer.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has repeatedly found the air at the crash site to be safe, but EPA representatives have been booed at recent East Palestine town meetings. Koester says she trusts “unbiased” news sources for information, like the Associated Press and NPR, but she too is skeptical about what the EPA is reporting. “Trusting the EPA only works if it’s not attached to a presidency,” she says.

Another Cincinnati mom, Lucy*, is relying on word of mouth information from her dad, who lives closer to the accident. Originally from East Palestine, where her dad still lives, she’s concerned there’s much more of a threat downriver than for those living near the original crash site. She worries that the threat will continue for years: “It’s a huge plume of toxic chemicals. It’s going to end up in the soil at the bottom of the river.” (EPA testing has confirmed the presence of chemicals in soil at the derailment site, though not in Cincinnati at this time.) Despite no official advice to do so, Lucy is installing filtering systems in her home and stocking up on bottled water.

If anything, the pandemic taught us that we do not, as a nation, share a trust in any one governmental body or agency. In the era of “do your own research,” moms like Lucy and Brittany are driven by a real panic that the very water and air their children are drinking and breathing may be poisonous. They’re struggling to sort through the flow of conflicting information and “fake” news to find concrete next steps on how to proceed, how to protect their families. It’s very hard to “wait and see” when your child’s well-being is at stake.

In the United for East Palestine Facebook group, a few days ago, a nonprofit organization called The Brightside Project asked what the children of the town need by way of support. A commenter warned: “Keep pushing for the truth.”

How to find credible sources in an environmental crisis

We spoke to veteran environmental reporter Kara Holsopple about how to find credible information in an environmental crisis. Holsopple and her team at the Allegheny Front, a public radio program covering environmental issues, work in nearby Pittsburgh, only about 40 miles from East Palestine, and they have been reporting on the events downriver. She says it makes sense local residents are confused in the wake of a disaster. “What I can say is that misinformation, conflicting information, or incomplete information seems to creep in or pop up in the places where there are no easy answers.”

Holsopple recommends WNYC’s On the Media podcast episode “The Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook” as a great source for anyone experiencing an evolving dire situation. “Their first point is that in the immediate aftermath of a shooting or disaster, news outlets will get things wrong,” says Holsopple. That doesn’t mean residents should necessarily lose trust in that source. “You should expect that, as they work to get it right.” She says to look to local news; find sources as close to a concerning incident as possible.

“News organizations and journalists should offer you the facts as they know them, multiple voices, sources, and perspectives, and some context if they can,” she says.

But what should you make of all the TikToks, viral photos, and citizen reporters that gain popularity after any crisis? Holsopple says to approach anything you see with a healthy dose of skepticism — especially if it’s drawing conclusions. Holsopple is instinctively wary of people who seem to have uncovered “the truth” soon after an event or claim to have explained things “in a nutshell.” That’s not possible yet in this case of East Palestine and won’t be for a long time.

The American Press Institute offers a simple guide for determining if a source can be trusted. Libraries and colleges teach students the CRAAP method, too. Readers can use this acronym to decide if the information might be valuable, or, well, crap.

Johnson, the therapist with expertise in crisis and trauma, points in particular to the “R” of the CRAPP method if you are experiencing panic or anxiety around news consumption about alarming events. Are you “bingeing” to the point of becoming upset? She says the entire process can help you realize when to take a step back and reconsider what you do and don’t still need to know, and where to find it.

Locals will likely be wading through information — and misinformation — for the foreseeable future. While Wagoner and her family await more details on the fallout from the disaster, her 3-year-old son, Wyatt, pretends he was at the crash scene as he plays with toys. His parents know he’s just processing through play. In some ways, he will have an easier time navigating the tragedy without constant bombardment from social media and dubious news sources. “Me and my friends put out the train fire,” he tells Romper. “It was a little scary, but we moved our horses.”

* Name has been changed for privacy.