Books

The "Housewife" Is A Thoroughly Modern Invention. A Better Model Lies Deep In Our Past.

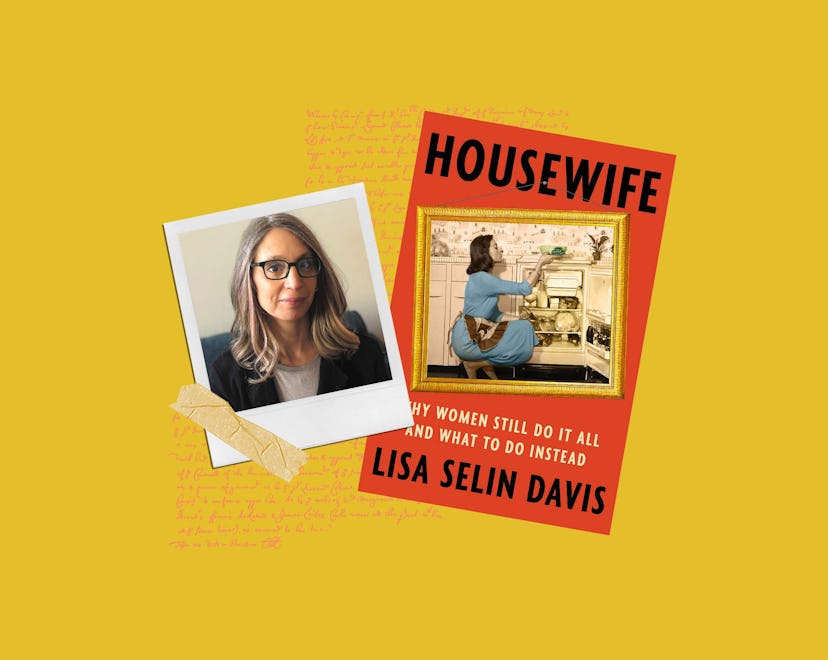

In her new book Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All And What To Do Instead, Lisa Selin Davis explores why the myth of the domestic goddess has such an enduring hold on us.

Though I had planned to start a family much earlier than I did — it took a long time to find the right man for the job — at the ripe old age of 37, I finally became a mom. Two weeks after my daughter was born, my husband’s work schedule intensified at his corporate creative job, which provided the health insurance and paid the bulk of our rent. So I spent my days tending to our child and our apartment: cooking, cleaning, and knitting hats.

On some small level, I had the life I’d wanted, even if I was a decade older than I’d hoped to be when it began (and I wasn’t living in a Craftsman bungalow in a college town but in my same duct-taped-together fourth-floor walk-up). But so much confused me about it. As an underemployed freelance writer in the curdled 2009 economy, I didn’t earn enough income to justify a full-time nanny. If I paid someone else, how would I turn a reasonable profit? I had absolutely no idea how the seemingly opposing trajectories and desires for both a career and motherhood could peacefully coexist.

From the women in my local moms’ group who’d nannied up and slipped back into their suits, there wafted a slight smugness, albeit often followed by guilt. From those a year in and still breastfeeding and co-sleeping and attachment parenting escaped a slight sense of superiority, often accompanied by a hint of inadequacy and insecurity. Regardless of the choices we made, even for those of us lucky enough to be able to make choices, we felt bad.

Meanwhile, those of us married to men started noticing that the emotional and domestic labor divide felt very 1950s, even though the majority of moms work — which led to a lot of complaining, both about our husbands and ourselves. Once I had a second child, and I tried to buy my way into better parenting through cheap stuff from Amazon, our clutter clogged the railroad apartment’s long hallway. I found myself regularly overwhelmed with a visceral rage mad at the state of our place; at myself for not training my children to tidy; at their dad for the Pigpen-like genes he must have bestowed upon them; and at myself for not achieving a single Instagram Momfluencer moment. I felt like a perpetual failure, and wondered why each of my mom friends was in her own home, trying to figure out how to work, cook, clean, exercise, and spend quality time with her kids.

When Donald Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett, mom to seven, for the Supreme Court, I began to fantasize about a reality show called Childcare Arrangements of the Rich and Famous. What was the secret? There seemed to be no map for the road I was traversing.

Housewife is an archetype, an insult, a dirty word, but most of all it is an enduring idea of what women should do and be.

One woman I’d met didn’t seem to share those feelings. She described herself as a “housewife” before she had a child and became a stay-at-home mom. I’d never heard a woman of my generation refer to herself this way, and wondered…was she happier? Between that and Trump’s conjuring of housewives in his 2020 reelection stump speeches and tweets, I went searching for the history of the housewife in America, asking how much of our private lives and public policies were based on the expectation that women would do it all. The pandemic had exposed the American “mother-as-social-safety-net” problem; what was the solution?

Over and over, I found myself surprised at what I learned. Archaeologists had unearthed a 9,000-year-old female skeleton that seemed to belong to master a hunter—or rather, huntress—suggesting that working motherhood was normal from the beginning of human history. Under “Republican motherhood” after the Revolutionary War, fathers were the moral center of families. Mothers’ and housewives’ premier task was raising children to become proper American citizens; women stayed home to rear and educate the kids (especially sons) so they could venture out into the world. But that meant women had to be educated themselves, and sometimes daughters, too.

In the 19th century, the American government heavily subsidized immigrant families to move West along with the expanding railroad: the Swedes to Kansas, the Poles to Nebraska and North Dakota. No western family would’ve accessed water, land, transportation, or economic development without government assistance.

Community-created institutions performed functions we’d think of as familial today: lodges opened by immigrant groups to assist financially and socially; funeral aid societies and sick or death benefit associations assumed by laborers; unions and religious institutions, taking as their mission helping members and parishioners in monetary or emotional need. The Catholics had godparenting. Some Native Americans had “blood brothers.” Black communities had “going for sisters.” Those independent pioneer families we heard about were, in actuality, deeply interdependent. On some level, they replicated the clans of early humans, in hunter-gather days — or maybe in huntress-gatherer days.

What really changed our expectations was the 20th century post-war baby boom. By the end of the 1950s, the average age at marriage was 20. The divorce rate decreased, the birthrate increased. Between 1947 and 1961, the number of American families grew by 28%. After a steady campaign to get Rosie the Riveters off the wartime assembly line and back in the kitchen, we desperately needed housing.

The Federal Housing Authority created low-cost mortgages, and private investors infused their cash into the housing market. Financed mostly by the government, the 1956 Interstate Highway Act drew 41,000 miles of national highways across the landscape. Funds siphoned from public transit that served dense cities were funneled into roads that supported private transit in less densely inhabited, less urban new frontiers. Nearly half of suburban homes were financed by the government.

Many women still believe that they should be shouldering the demands of the domestic front solo.

With their own yards, swing sets, and even bomb shelters, suburban homes became fortresses. Television sets replaced communal movie theaters. Washing machines replaced public laundromats. Swing sets replaced playgrounds. Suburbia thus created “an architecture of gender,” literally building in the homemaker/breadwinner divide. We traded extended family and community ties for modern conveniences. We traded in our clan for what historian Stephanie Coontz called “the most atypical family system in American history”—one that is now, ironically, considered “traditional.” It is anything but.

With the dawn of second wave feminism, and the acknowledgement that this new way of living had in fact left a lot of women deeply unhappy, more women returned to work. But the 1971 universal childcare bill that could have made that shift easier on everyone was vetoed by President Nixon. Women who’d had the privilege of not working could now suit up for the office, but the various ways that women had been supported by extended family and community had faded by then; the expectation of doing it all — that 24-hour woman ideal I was raised with — prevailed. Though men do more than they used to, even breadwinning women now do more housework than their husbands.

The ghostly shadow of the housewife, its unsustainable ideal, hovers over women, making them feel that whatever they’re doing isn’t right, isn’t good, isn’t enough — especially those moms who must or want to raise children full time. There’s a pervasive and poisonous capitalistic American notion that women’s work and their unpaid labor is un-valuable, that somehow selling dental equipment or delivering packages is more important than changing diapers and breastfeeding. But in fact, the unpaid labor of women is invaluable. Paid labor cannot be accomplished without it.

Housewife is an archetype, an insult, a dirty word, but most of all it is an enduring idea of what women should do and be. Until we understand how it has shaped policy and perceptions across decades and centuries, we will not be able to move forward.

By the end of my research, I felt better about, well, how bad I’d felt. Very little about the way we live today replicates the clans our species was meant to partake of. With church attendance down, social media replacing in-person contact, and a stigma to needing or getting help, many women still believe that they should be shouldering the demands of the domestic front solo. I disagree. I think the most important thing for parents to do is replicate the clan in any way they can.

For some people of means, that could include paying people to occupy the role extended family members once would have, to help with childcare and cleaning. For others, that could entail founding a babysitting co-op or other models of shared childcare, finding community organizations to join and support. Maybe others want to organize and lobby for universal childcare and paid family leave for all. The clan can be a combination of personal, community, and structural supports—but sadly, until we let go of the idea that women are supposed to perform the role of housewife, no matter what else they do, they’ll have to fashion that clan themselves.

Excerpted from Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All and What to Do Instead, copyright © 2024 by Lisa Selin Davis.