Books

Kate Baer Wants To Know Why Moms Aren't Rioting In The Streets

Same.

“Oh hell yes.” “Preach.” “Ugh YES!” “Same same same.” “It’s like she can see inside my soul.”

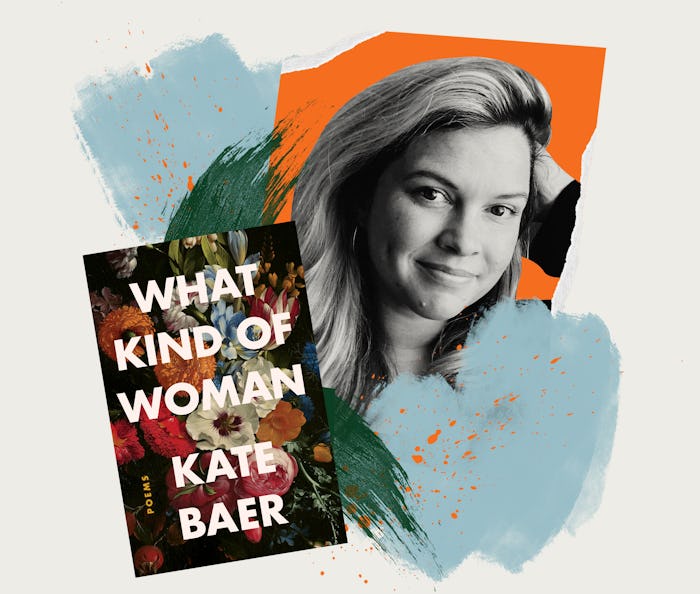

She is Kate Baer, whose poems have gone viral again and again on Instagram, and whose work I’ve been devouring since a friend pointed me in her direction several months ago. Baer’s poetry offers insights into both the mind-numbing and heart-exploding truths of motherhood and womanhood. And especially right now, when mothers and women are expected to pick up the slack for the whole of a broken system, her debut book, What Kind of Woman, is like that best friend who totally gets it and also is furious on your behalf.

In “Moon Song,” Baer writes about the inherent contradictions that exist within motherhood: “You can be a mother and a poet. A wife and / a lover. You can dance on the graves you dug / on Tuesday, pulling out the bones of yourself / you began to miss.”

After the birth of my first child, I was shocked to feel a flattening of my selfhood, as if assuming the heavy mantle of “mother” had erased my individuality. “Moon Song” is a beautiful refusal to submit to cultural erasure, and the poem feels especially poignant now, when mothers are being asked to subsume vital parts of ourselves so we can serve our families, whether it be as caretakers, educators, or otherwise.

I asked Baer about her own experience coping with identity shifts and motherhood via email. “Daniel Tiger says it best when he sings, ‘You can feel two feelings at the same time, and that’s OK,’” she tells me. “You can love being a mother and also want to be away from your children. You can love your husband selflessly and also desire independence and equity in marriage. You can be a poet and also watch trash TV on Friday nights with a bag of chips. Motherhood often asks us to choose either/or, but I’m learning I can have both.”

You can love being a mother and also want to be away from your children.

Baer also writes about the relentless grind of motherhood: “What I mean when I said ‘I haven’t really been / reading’ is that / sometimes I imagine what it would be like to fall / asleep on a moving / train and wake up on the other side.” Baer says she wrote “What I Meant” during a frantic pre-pandemic week, when she had dropped several mom balls, including screwing up dates for pajama day. Now, of course, we’re all nostalgic for the “before times” flavor of bad days, days that were made bad not by surging COVID cases or failed attempts to teach number bonds to one’s first-grader, but by sending kids to school in jeans instead of Elsa and Anna PJs. “I’d give all my money to let my kids go back to school and miss pajama day! At least they are at school!” Baer says.

The fact that bars, restaurants, and casinos remain open and so many schools are closed clearly demonstrates how our country’s leaders prioritize mothers, children, and the value of child care. “This pandemic showed all our country’s cards when it comes to how we treat mothers. It is shameful,” Baer says. “We are now expected to keep our careers while also being full-time teachers, caretakers, and safety police. I am truly astounded that we aren’t rioting in the streets, and I’m talking to myself here.”

I’m working on this interview during the last half-hour of my baby’s nap, trying not to hear my son’s second-grade teacher exhort him to unmute himself whilst my 6-year-old daughter bleats something about needing help cutting her sandwich. So as to rioting in the street? Same, girl, same.

Like all smart women who attain a certain degree of success, Baer is frequently trolled, and her treatment of these (read: male) trolls is utterly delicious. In response to a man named Chad (you can’t make this up) who wrote that he’d buy Baer’s books for his daughters “as an example of what NOT to be like,” Baer spliced Chad’s original message to create the following poem: “it’s funny how / men go ahead and / have / daughters / Even though / They / can’t fathom / what / daughters can be.” These response poems garner some of Baer’s biggest Instagram reactions (25,777 people liked the “Chad” poem), and I have to imagine it’s because Baer’s public and brilliant evisceration of misogynist detractors feels like a win for us all.

Indeed, when Baer’s poems are tagged or shared in Instagram stories and DMs, there’s a collective nodding that seems to accompany these exchanges, like “yes, yes me too!” And this sharing makes us feel less alone, less gaslighted. As mothers, we’re given pink cards on Mother’s Day celebrating “the most important job in the world” while simultaneously being told through lack of financial, social, professional, and even medical support that our labor is unimportant, unworthy of financial compensation or cultural respect.

I asked Baer if she thought her unflinching acknowledgment that the experience of motherhood is crazy-making for very specific, structural reasons (sexism, racism, capitalism), and not due to individual shortcomings, has contributed to her wide and passionate readership. “I was surprised that so many people would embrace poetry; I was not surprised at the collective anger or grief over the weight of motherhood,” she says. “All of us want to feel seen in our experiences, and telling the truth about what is happening structurally lends itself to a giant ‘me too.’ I live for the gritty and unfiltered realities of what is actually going on behind the scenes, in motherhood and otherwise. Take the hit show Fleabag for example. Here we have a woman peeling back the very unfiltered reality of dating and sex and loving yourself. There is a reason women across the country gave it a collective standing ovation. It was like, 'Oh, yes, this. This is what it really is.'”

Baer’s exactly right: Art that proclaims, “Yes this. This is what it really is” is a gift. Everything feels so hard, so big, right now, and often, my rage feels impotent and pointless in the face of the mundane realities of life. I am tired of shaking cereal into bowls. I am tired of being told I poured too little or too much milk. I am tired of worrying the baby will choke on cereal. I am tired of telling children to clear cereal bowls. I am tired. But I feel stronger when reading Baer’s poems because her poems hold my exhaustion, my hopes, my furies.

In “Fortune Telling,” which takes my breath away with a feeling of being seen, Baer writes: “Even though I still have my own / young children, even though they / rake my body over until it’s limp / with decay, even though I cannot / bear the sound of another child / calling for his mother — I know I / will be one of those old women / who walks up to your family and / says: look, you are so beautiful.”

What Kind of Woman is on sale Nov. 10.

This article was originally published on