Life

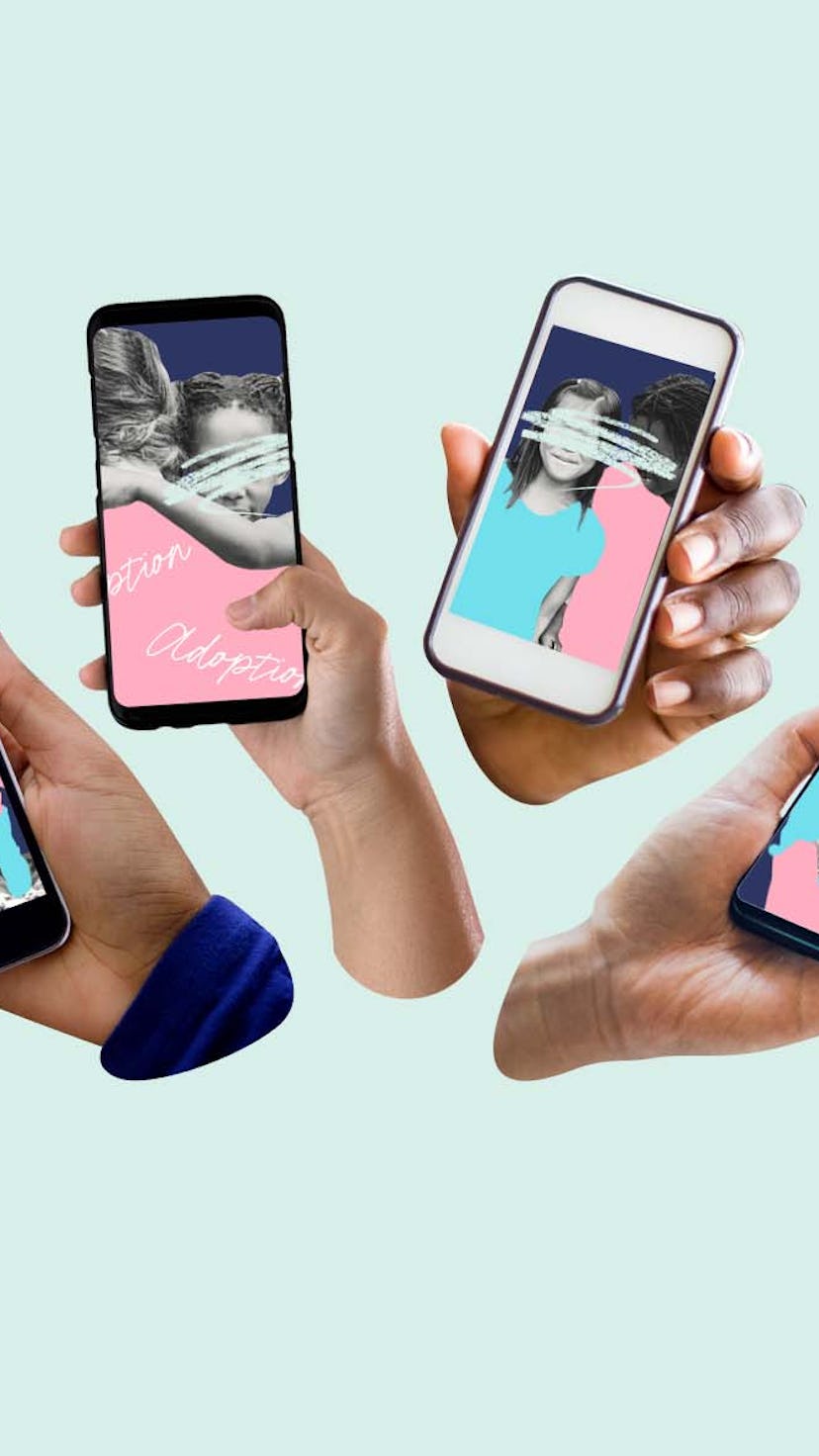

These TikTok Creators Are Using The Platform To Change How We Think About Adoption

Adoptee TikTok is hoping to expose the uncomfortable truths about a flawed industry, and its impact on the adopted children themselves.

When Kirsta, a Milwaukee art teacher, was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, she started making Instagram reels to vent about her experience as an adoptee. In some of her most-viewed videos, Kirsta (who requested we use her first name only), calls out “mommy bloggers” who she sees patrolling Facebook groups looking for children. She pulls up the screenshots of unsettling posts that say things like “I’m looking for a pregnant teen in hopes of adopting her baby.” Kirsta’s features — curly dark hair and large, expressive brown eyes — are unmistakably Greek. Besides the videos calling out what she referred to as “pregnant people poaching” on Facebook, her most popular content is her short vlogs about discovering her Greek culture through trying new foods, practicing the language, and planning her trip to Greece to meet her birth family.

Kirsta tells me that as a child she was paraded around as the poster child for her adoptive mother’s private adoption service, which, for a fee of around $4,000, helped clients find children to adopt. “I never liked it. I felt like a car in a showroom,” she says, saying that the experience showed her early on that adoption wasn’t the wonderful thing her mother’s business pamphlets made it out to be. “I always understood how commodifying adoption was," she says. "I always kind of knew it was bullshit.”

Those formative adoption pamphlets her adoptive mother handed out to prospective parents? They featured photos of Kirsta with text that said something along the lines of, I want to make other people as happy as my daughter has made me. “It was all about the adoptive parents and it is not centered around the needs of the adoptive child,” Kirsta was quick to note. “Adoption is supposed to find a family for a child, not find children for people’s family-building purposes. That's the narrative I am hoping to start shifting.”

Kirsta told me that when friends encouraged her to start telling her story on TikTok, she initially hesitated. “I was like, ‘I’m a millennial, I don’t do TikTok,’” she joked. Now has more than 130,000 followers on the video platform under the username karpoozy, which is a variation of the Greek word for watermelon, “karpouzi.”

Kirsta is just one of several adoptees on TikTok who are telling their stories in hopes of exposing the uncomfortable truths about adoption and its impact on the most powerless people involved — the children themselves.

Alé Cardinalle is an international adoptee who goes by the username wildheartcollective_ on TikTok. After she noticed a trend of adoptive parents oversharing their adopted children's stories on the app, Cardinalle started making videos addressing adoption rights and reform. Like many adoptees, Cardinalle feels that it's not appropriate for adoptive parents to be growing a following and potentially monetizing an adoptee's story. But when Cardinalle messaged an adoptive father to ask that he keep his adopted children’s stories private, he dismissed her concerns and blocked her. When she made a video about that interaction, it found its way onto adoptee TikTok, and her advocacy work began.

“I and the adoptees I know are very protective over our stories because we never had agency over them growing up,” Cardinalle told me over the phone. “People told us how to think and feel, and a lot of us were given wrong information."

Until she met her birth mother and heard her story, Cardinalle says she didn't know about what she calls the "dark side" of adoption. “I realized that maybe the adoption didn’t need to happen if my birth mother had been paid a living wage, and if the first solution presented to her wasn’t adoption.”

“In an ableist, racist, classist system, it is hard to pinpoint what is an ethical and necessary adoption.”

Cardinalle later learned about the less savory elements of the history of adoption in the United States from the no longer active “Not Your Orphan” YouTube channel, started by Blake Gibbins, a nonbinary adoptee rights educator who studied child welfare history and contemporary adoptee rights. On the channel, they discussed topics like adoption misconceptions, the story of Georgia Tann, and what's known as the "baby scoop" era.

The American adoption industry and foster care systems are inextricably linked, and today, children in the U.S. are placed into foster care primarily because of neglect. Neglect, as Jerry Milner, associate commissioner of the U.S. Children’s Bureau and his special assistant David Kelly establish, often operates as code for poverty. According to the Department Of Health and Human Services, 52% of the over 64,000 children and youth who were adopted in 2019 were adopted by their foster parents. “A person who can’t make ends meet shouldn’t permanently lose their children,” asserts @shesfindingfree, an actor who was adopted as an infant from foster care, and who asked to go by her TikTok username for this story.

Addiction is another primary reason children are sent into foster care. According to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics that analyzed nearly 5 million instances of children entering foster care between 2000 and 2017, nearly 1.2 million entries were attributable to their parent's drug use. Activists and researchers question whether the birth parents' custody loss is the least harmful form of intervention.

Cardinalle points out that with the right support, birth parents can recover from substance abuse disorders and regain custody when they are able. “Are all terminations and removals right and just in a system that we know targets Black and brown poor families and that demonizes people with mental health disorders?” she wonders. “In an ableist, racist, classist system, it is hard to pinpoint what is an ethical and necessary adoption.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics labels adoption as a traumatic event, even when the child is adopted at birth. In addition to PTSD, adoptees face higher rates of substance abuse disorders and eating disorders, and are four times as likely to attempt suicide, according to a 2013 study published in Pediatrics, the AAP’s journal.

We are quick to digest the narrative that adopted kids come with trauma and baggage from their first families, but for some adoptees, the most traumatic experiences occur in their adoptive homes. But because of societal expectations that emphasize gratitude and saviorism, it is difficult for many adoptees to name or even become aware of the psychological abuse they may have faced in their adoptive homes.

Kirsta, aka karpoozy, says there is a stigma around getting help for mental illness as an adoptee because of the persistent idea that adoption is a "beautiful solution that makes children’s lives better."

In the adoption community, this positive adoption narrative is known as “The Fog.” The Fog does not offer a nuanced view of adoption and leaves no room for grief, anger, resentment, or any of the other emotions adoptees may be feeling — besides the expected happiness and gratitude towards their adoptive families.

Like many people, Cardinalle grew up thinking adoption was a gift, a beautiful thing birth parents did to give their children a better life that they themselves could not provide. Before she knew she was adopted, her struggles to make friends and concentrate in school were attributed to attention deficit disorder (ADD). “I understand now that nothing was wrong with me, something happened to me and what I was going through was a trauma response.”

“I came out of The Fog in little baby steps and then all at once and there was a lot of grief, anger, and relief. Everything fell into place and started to make sense.”

“It is so normalized and such a slow burn, you don’t even process what is happening. I didn’t till I was 33,” @shesfindingfree said. When she was 12, her adoptive mother told her, “‘I named you Tiffany, after the store, because you were expensive.’ “What was I supposed to do with that as a child?”

“I wish unnecessary adoptions didn’t happen. I wish every parent that would parent if they could had the resources they needed and that adoption was the last resort in a crisis, when all other avenues are exhausted.”

Abuse within the adoption industry aside, these TikTok creators tend to consider adoption as inherently unethical. Their central concern is the stark fact that money is legally exchanged for a human being, but they also cite the fact that the decision is irreversible, with permanent changes to an adoptee’s birth certificate (adopted children receive amended birth certificates and, in some states, biological information like their birthplace is changed to the adoptive parents’ residence). Medical records and other information related to their biological families can be missing from adoptees’ files, leaving them in the dark about genetic predispositions, medical conditions they should be aware of, and their own ethnicities and nationalities. To Cardinalle, the fact that adoptees’ original birth certificates are sealed in most states speaks volumes. “We shouldn’t have to jump through hoops to have the information that most people never question.”

“I wish unnecessary adoptions didn’t happen,” Cardinalle tells me. “I wish every parent that would parent if they could had the resources they needed and that adoption was the last resort in a crisis, when all other avenues are exhausted.”

When it is absolutely necessary that a biological parent’s rights are terminated or a child is orphaned without other biological family members who can care for them, the TikTokers have lots of ideas for how the adoption process and industry could evolve into something that is more ethical and less traumatic.

For the approximately 120,000 children in foster care who are waiting for adoption in the United States, Cardinalle believes the best solution is something called "permanent legal guardianship." This arrangement grants guardians almost all the rights of a parent but does not change a child’s birth certificate. It gives children the power to consent to being adopted by the guardian(s) if they choose, when they are ready to make that decision. When and if a child consents to being legally adopted, Cardinalle says a certificate of adoption rather than a new birth certificate would be a better way to document the decision.

As for the overall lack of consent in the adoption process, Kirsta proposes that all parties refrain from finalizing paperwork until a child is older. Based on what we know about child development, she says a child should have to be 12 or 13 to be able to consent to adoption, with, ideally, a neutral third party who can inform and guide them through the decision process.

Creating change in the adoption industry is complicated, but these creators point out that changing language is one way to make more immediate improvements.

For instance, Mia (@miathaicha on TikTok), a transracial queer adoptee from Haiti, says she hates when people say “real parent.” “All parents are real people. [That phrase] puts pressure on us to choose between them.” @shesfindingfree and TikTok creator @pittiemama87, who prefers to go by “Pittie,” both cite adoption language being used for shelter animals as their biggest complaint.

“It is so dehumanizing that we use the word ‘adopt’ when we talk about highways and animals,” Pittie said. She recalled seeing “Adopt a Highway” signs as a kid and finding them deeply hurtful.

Mia also wants adoptive families to examine the way they speak about 'saving' children and take care not to posit themselves as “better” than birth families. “My adoptive grandmother always threw in my face how much ‘worse’ it could have been," she says. “That didn’t allow me space and time to feel sadness. Even if our birth parents couldn't provide, it’s still a loss and we should be allowed to grieve.”

Over email, adoptive parent Shelby Henigman tells me that she is "extremely grateful" for the stories of adoptees, told in their own voice, and credits them with helping her be a better parent to her son. "I have learned to not only look for good adoption stories but also sit with the uncomfortable. I have learned the importance of language and the damage of not educating those around me. I have learned the need for empathy and compassion for my son, his story, and the pain that comes with his trauma."

The adult adoptees of TikTok hope their advocacy leads to change in the adoption industry, while acknowledging that systemic change is largely beyond their control. On an individual level, it's clear these voices have had a sizable impact. “I get comments from people that say ‘You changed my mind.’ That is why I do this,” says Cardinalle. While an avalanche of negative feedback is par for the course for all of the creators, she explains that ultimately it is worth it for the way they have been able to change the conversation.

“I hold parents of today to a much higher standard. I was adopted in 1988 when there was no internet, no one in your pocket sharing their experience. I give my parents a lot of grace I wouldn't give to adoptive parents in 2022.”

One adoptive parent, who goes by InventingNormal, was profoundly affected by the conversation Tiktok. "I have learned more from them in the past year than in our nine years of being involved with the system," she told me over email. "It’s a debt I don’t think we will ever be able to repay, but I will spend every day trying." InventingNormal's family was in the process of finalizing the adoption of their own twins — and documenting the whole process on TikTok — when she came across Alé Cardinalle's account. Over email she tells me what it was like to overcome her initial defensiveness and open herself up to the possibility that she had misstepped. "I remember being very offended," she told me over email, "I was a typical I'm not doing anything wrong! adoptive parent. I very much had the mindset of If I can just get into her DMs and explain, surely she will see that this isn't the case in our situation.” She says Cardinalle managed to stay matter-of-fact but patient with her as they argued for close to an hour. "We ended the conversation politely agreeing to disagree but that night after putting the kids to bed, I couldn’t get the conversation out of my mind," she says, explaining how she went back through their correspondence at three in the morning to give it a second look.

"If I’m being honest, I was probably doing it to prove myself right. I ended up seeing with my own eyes exactly what Alé was saying. We were in fact telling stories that were not ours… and worse, we were telling them from our point of view. I don’t remember the exact number of videos I removed in those early morning hours, but I want to say it was in the high 90’s." InventingNormal said she reached out to Cardinalle at a reasonable hour to apologize, and that after many more conversations, their family changed more than just how they created content on TikTok: They have since made the decision to pursue legal guardianship for their twins, who are now 5, rather than finalize the adoption. "Since being educated on all of the possible harm removing informed consent from a child can cause, we have chosen to wait until the twins are old enough to understand what adoption entails, as well as express their desire (or not) to move forward with the process. This would absolutely not have been something we would have considered before Adoptee TikTok."

“I hold parents of today to a much higher standard,” Cardinalle said. “I was adopted in 1988 when there was no internet, no one in your pocket sharing their experience. I give my parents a lot of grace I wouldn't give to adoptive parents in 2022.” Now those parents have places like TikTok, and voices like Cardinalle's, to help guide them.

What adoptee TikTok wants adoptive parents to know:

Be honest with yourself about why you are adopting.

The narrative around adoption is that it helps a child, but the industry centers adoptive parents and their personal, sometimes self-serving reasons for adopting. Adult adoptees hope prospective adoptive parents can be open to doing the hard work of self-examination, even when it is uncomfortable.

As tragic as it can be to struggle with not being able to have biological children, Pittie wants people to know that adoption will not heal infertility or miscarriage trauma.

Don’t keep the adoption a secret from the child.

@shesfindingfree wasn’t told she was adopted until she was twelve years old, and she described finding out as the “world being pulled out from under her.” “The worst thing you can do is to wait to tell the adoptee, “ she said. “It should always be a part of their vocabulary and their story. They should never remember being told they were adopted.”

Look to adult adoptees for guidance.

“Maybe if adoptive parents thought of adult adoptees as experts in the field of adoption," says Pittie, "they would listen and learn from our lived experience.”

Kirsta revealed that Romper was the first parenting publication to reach out to her for an interview. “People rather listen to happy stories rather than lived experiences. You need to listen to all adoptee experiences, not just ones saying things you like to hear.”

“You never know what your adopted child might say to you down the road, and listening to adoptees will prepare you.”

Go to family therapy.

“Having the whole family in therapy helped me and my adoptive parents so much, but we didn't get there until my 20s. It would have been a game-changer for me as a kid,” Cardinalle shared. “I was in therapy at eight years old but the angle was, ‘What’s wrong with her? How can we fix her?’ There was nothing about adoption.”

Keep adoptions open.

Open adoptions are not legally enforceable, so it is up to adoptive parents to make the effort to stay in touch with biological families, provided the biological family also consents. “If you are an adoptive parent it is your responsibility to bend over backward to make contact with the birth family work and integrate the family into the adoptee’s life,” Cardinalle said.

“Open adoption is not just sending pictures back and forth; it should be in service of the adoptee.”

Many adoptions are kept closed as adoptive parents are trying to protect their own feelings, or they assume biological families are “unsafe.”

“We need to get rid of the assumption that birth families are terrible people because that’s not what I found when I found my family,” @shesfindingfree said. “I found scholars, veterans, beauty queens, opera singers…I even have a distant cousin relation to Walt Disney.”

@shesfindingfree was always told she was “better off” being adopted, but it was clear to her that “better” only meant her adoptive family had more money. “I didn’t just need materialistic things, I needed family. I needed people who looked like me.”

No matter how much you love and provide for your adopted child, they still deserve to have contact with biological family members who are safe.

“Growing up knowing someone from my biological family was thinking of me would have rocked my world in the best way,” Cardinalle said.

Help your child connect with other adoptees.

For the people of adoptee TikTok, finding a community of like-minded adoptees has been so healing.

“Being an adoptee is my culture,” Cardinalle said. “When I am in community with adoptees is when I feel most seen and heard because we have a shared language I don’t get anywhere else.”

Cardinalle recently hopped on a plane to meet Pittie, who said she really wishes she had known other adoptees as a child.

Race and culture matter.

In adoption, people like to pretend that racial and cultural differences won’t matter, and that love is enough, but the transracial adoptees of TikTok know firsthand that racial and ethnic mirrors are critical for a child’s identity.

Mia was fortunate enough to visit Haiti as a child, but she wishes Haitian culture had been incorporated more into her childhood in the form of food and artwork. Her own daughter’s father was adopted from Colombia so she is aware of the loss of culture her daughter will experience on both parents’ sides and knows the importance of providing her child with some connection to both countries.

Kira Schaubeck, an Orlando-based artist who was adopted from China by a white lesbian couple, says she internalized racism that further deepened the disconnect between her and the Chinese culture she lost.

“Pittie,” was adopted from Romania in the 1980s via a "baby broker" who posed as a doctor and told Pittie’s birth mother that her 4-year-old daughter needed life saving heart surgery in America. Pittie, who is not only Romanian but also Roma, suggested that adoptive parents move to neighborhoods where people of their child’s race live.

@shesfindingfree is a Black woman who was adopted by a Black family, but because she is darker than anyone else in the family, she said her adoptive mother never really listened to or understood anything about the colorism she faced in the Black community.

Accept that adopting will not be the same as parenting a biological child.

“I didn’t need to be loved like I was their own, I needed to be loved like a child who was somebody else’s who they had the privilege of caring for,” @shesfindingfree said. “If you cannot honor that a child has a history, a bloodline that has nothing to do with you, don’t adopt."

You are not a saint; adopted children do not owe you anything.

“Adoptive parents are just people. They’re not saints just because they adopted,” @shesfindingfree said. “Children don’t owe you unyielding gratitude just because you decided to be their parent.”