News

Missouri School Brings Back Spanking As Punishment

A Missouri school has reinstated corporal punishment as a form of discipline.

The Cassville R-IV School District in Missouri is responsible for about 1,900 students over four schools. In 2001, the district banned the use of physical punishment — such as spanking or paddling — as a means of discipline. But after a survey was distributed to parents, staff, and students this past May, the district, led by Superintendent Dr. Merlyn Johnson, reinstated corporal punishment as a way of handling disciplinary issues.

The revived policy, which was enacted in June after the 2021-2022 academic year ended, allows a staff member to use “reasonable physical force ... for the protection of the student or other persons or to protect property,” as well as restraint of students. “Reasonable physical force” is not defined beyond language that states such force must pose “no chance of bodily injury or harm” and that children cannot be struck on the face or head. Corporal punishment in Cassville is also an opt-in program: parents in support of the policy have to, essentially, sign up for it. Parents will also be notified before their child is physically disciplined, which will be done “only when all other alternative means of discipline have failed, and then only in reasonable form and upon the recommendation of the principal” in the presence of another employee.

Johnson says that reinstating corporal punishment was not his aim when he took the job in Barry County last year. “I didn't want that to be my legacy and I still don't," he told the Springfield News Leader. “But it is something that has happened on my watch and I'm OK with it.”

According to Johnson, some parents had urged the district to reinstitute corporal punishment, and that locals have responded more favorably to the news than national outlets and social media. “We've had people actually thank us for it,” he explained to the News Leader. “The majority of people that I've run into have been supportive.”

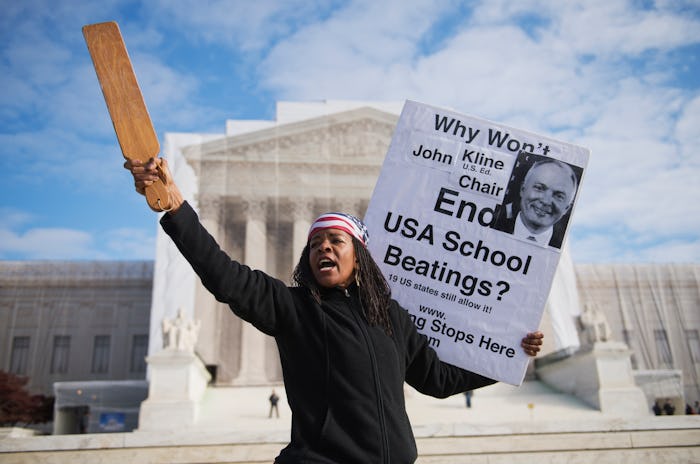

While most states have either outright or de facto banned corporal punishment in public schools (it is still legal in all private schools with the exception of New Jersey and Iowa), physical discipline is still legal in 19 states, mainly in the South. States’ rights to allow such punishment was last settled in the 1977 Supreme Court case Ingraham v. Wright, when the court ruled that the ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” enshrined in the Eighth Amendment only applied to the treatment of prisoners. Children at school — from pre-school to high school — they said, were not protected despite the fact that, as Susan Bitensky points out in her book Corporal Punishment of Children: A Human Rights Violation, in any other context, the act of an adult hitting another person with an object, such as a paddle commonly used in schools that allow corporal punishment, would be considered assault with a weapon, punishable under criminal law.

In this, the United States is an outlier, particularly among so-called “Western” countries. As of 2016, more than 100 countries have banned corporal punishment in schools. These bans rose meteorically in response to the 1990 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, a treaty that requires nations to “take all appropriate measures to ensure that school discipline is administered in a manner consistent with the child’s human dignity” and has been ratified by every country except the United States.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has taken a similarly firm stance against corporal punishment of children, noting that painful physical punishment is associated with a bevy of adverse outcomes, including increased aggression in preschool and school-aged children, as well as mental health disorders, and — perhaps ironically to proponents — has been found to increase the likelihood of defiance and aggression.

A 2016 paper on the prevalence of corporal punishment in American schools found that over 160,000 children in these states are subject to such punishment each year for a wide range of offenses, from fighting and bullying to dress code violations and mispronouncing words. The paper also found that Black children, especially boys, and disabled children, were disproportionately affected by corporal punishment. This assertion was reiterated by Dick Startz, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara; writing for the Brookings Institute in 2016, Startz found that Black children were twice as likely to endure corporal punishment at school than their white peers. An update of his work this year found that while overall numbers of corporal punishment had gone down, his previous findings remained steady.

In February of 2021, Representative Alcee Hastings, a Florida Democrat, introduced H.R. 1234 — the Ending Corporal Punishment in Schools Act of 2021 — to Congress. There has been no movement on the bill since.

This article was originally published on