Family Dinner

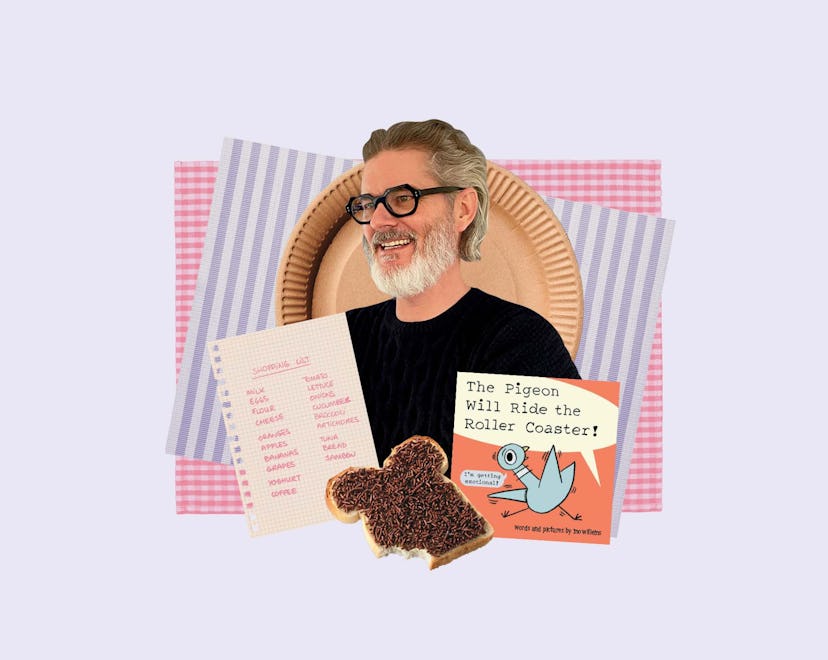

For Mo Willems, Dinnertime Is No Excuse To Stop Drawing

The beloved author talks to Romper about his new children’s book and his genius approach to mealtime.

If you’ve been in a classroom, library, or children’s section of a book store any time in the past 20 years, you’ve probably encountered author-illustrator Mo Willems. If you have children yourself, there’s a high chance you have read, or will read, his books to those kids every night for a good number of years. Willems has created more than 65 children’s books (or, as he says, “books for children and former children”), and his characters, from Elephant and Piggie, to Knufflebunny and The Pigeon, have become some of the most beloved of a generation. His latest book, The Pigeon Will Ride the Roller Coaster!, hit the shelves Sept. 6 and delivers all the laughs and Pigeon-y wisecracks we’ve come to expect from the prolific author.

As you can imagine, someone who has written and illustrated that many books (and been involved in musical adaptations, theater productions, apps, and animated series, and specials based on those books) is pretty much always creating. Even dinner, it seems, is no reason to stop drawing.

“We have consistently for, I don’t know, 12, 13, 14 years, put butcher block paper on the dining room table and crayons for everybody,” Willems says. When his son, Trix, was younger, they did this every night. “We’d draw and doodle and discuss our feelings through our drawings, what we were drawing about and sort of talking around things.”

Willems’ wife of 25 years, ceramicist Cheryl “Cher” Camp, usually draws abstract designs or ideas for pottery. Trix, who’s now in college, currently favors photorealist illustrations, portraiture, and landscapes. During one of these dinnertime art sessions, Willems sketched out what would become Elephant (aka Gerald) from his Elephant & Piggie series.

I would eat hagelslag, which is basically chocolate sprinkles and butter on bread. You would think the kids would be jealous and would want to have a bite of basically this chocolate sandwich, but they called it bird poop sandwiches.

Willems spoke to Romper by Zoom about these artistic family dinners and dinner parties, as well as the long-distance family cooking lessons he’s given his son, favorite meals from his travels around the world, and why food makes for such excellent reading material.

Jamie Kenney: I just want to start asking about the foods you ate as a child. What was your food culture like back then?

Mo Willems: I am the son of Dutch immigrants, so I ate Dutch food, and was teased quite a bit as a child for my sandwiches in particular. I would eat hagelslag, which is basically chocolate sprinkles and butter on bread. You would think the kids would be jealous and would want to have a bite of basically this chocolate sandwich, but they called it bird poop sandwiches. I Really Like Slop!, comes from often being teased for what was considered, at the time, ethnic food.

Food comes up a lot in your books. I Really Like Slop, The Duckling Gets A Cookie…

MW: Oh, that’s interesting. There’s a hot dog [in The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog], Should I Share My Ice Cream…

That’s Not a Good Idea, one of my personal favorites…

MW: That is culinary… and intense.

I have a theory as to why I think it continues to work well, but do you have any thoughts on why—

MW: No, let’s hear your theory.

Well, all of your books are character-driven stories about feelings. Food is a great source of emotion, for kids and adults, too, but kids’ experiences are more limited, so it’s a good way to establish stakes and drama: “I want a cookie” … “I don’t like that food.”

MW: One thing that I have noticed is that the majority of my audience eats: It’s just a thing they do. You could pretty much pick out anybody who has read any of my books and, at some point in the last two or three years, they have eaten.

But yeah, when you are writing books that are geared toward or marketed toward children, you don’t really have many cultural modifiers, right? You have to deal with love and jealousy and wanting to drive a bus. I do think food is fundamental and philosophical and cultural in some ways, but in a wider sense.

So we’ve talked about food in your childhood and food in your books. Would you say food plays a broader role in your life now?

MW: I would say that my wife very much likes to communicate through food. I have, over the last 30 years, become much more attuned to food and seeing food as a shared experience and as a cultural experience and experimenting with it. I am the sous chef. I am the chopper and whatnot. But often, if we do go out to eat — of course in the before times more than now — my wife would reverse engineer the meals in some way. That is a big part of just my daily life, always.

I never eat alone and we’re always talking about what the next meal is going to be and how it’s going to be made and where it came from and whatnot.

What about food after the pandemic?

MW: When the pandemic hit, my son was in college and in an apartment. What we did every Sunday was the three of us, my wife and I here and then my son in New York, we cooked the same meal at the same time. We would get the same smells simultaneously as we were making this meal. Then you also knew when the conversation was over. You never got to be the annoying parent, or, “Did you do your homework?” Instead it was “Oh, this smells delicious. I think we all got to sit down and eat it.” That was a really remarkable experience. It was a great thing to look forward to. Over the weeks and months, we went from really teaching him about cooking, to him then bringing in his love of certain cuisines, and particularly Korean food, and teaching us. That was a great way to survive the isolation from the pandemic.

Was this Trix’s first real culinary education or did you cook with him when he was a kid?

MW: We cooked a little bit with him. Yeah. But I think this is really the first time that “Go out and get the food. You figure out what it is. What do you have in your fridge? OK. We’ll come up with a plan.” He became much more serious about it, like “I really want to learn how to do X, Y, Z.” Then we would build a meal around that. It was great. It was a great experience. It was really, really fun.

Sometimes you would have someone who you did not think was artistically inclined and their drawings would be remarkable. We always recycled all the paper. It’s all about the process. But it made the meals much, much longer and you just didn’t need screens anymore. That was really joyful.

I understand that in “the before times,” you hosted a lot of dinner parties. Could you talk about those?

MW: We always [brought out the butcher block paper to draw on] whenever we had guests. Having guests who were consistent would be interesting because you could see how [their drawings] changed. My father-in-law, who had been a businessman, was very not interested in doing it and then started doing spreadsheets. Then those started to bend and then they became abstractions. Then he would want to go to museums to look at how colors match. He really developed this style.

Tony DiTerlizzi and Scott Fischer and Eric Carle, and all our neighbors who are incredible artists, made incredible pieces of art. But sometimes you would have someone who you did not think was artistically inclined, and their drawings would be remarkable. We always recycled all the paper. It’s all about the process. But it made the meals much, much longer and you just didn’t need screens anymore. That was really joyful.

The only person who ever was really afraid of it — it was interesting — was a guy named John G. Morris. He was the photo editor at Life. Published the first D-Day photos. He was the photo editor of the New York Times with the Agent Orange photo of the girl on the cover. What was amazing about it was to see someone who, at that point, was well into his 90s really still asking himself some fundamental questions about fear and growth and art.

You and Cher lived in Paris for a year, and from what I’ve read, you’re extremely well traveled from a fairly young age.

MW: Mm-hmm. My father and I walked across France when I was 15.

Do you have any thoughts on how your travels have affected your palate or favorite meals you remember from abroad?

MW: Oh, I have favorite meals, sure. Most of them are about the company that I’ve kept. Four or five years ago, I did a festival in Padua. It was a big Italian literary festival and the town had a culinary school. All of the authors would meet at this giant big table and all of the culinary students just fed us the entire time.

Oh, my God. That sounds like a dream.

MW: That was a really remarkable experience. I remember being in inner Mongolia. They wouldn’t let us into a hotel for some reason. It was me, a Japanese guy, a Swiss guy who’s still a friend, and a Swiss gal. We made such a stink that they brought us to a government hotel, and we had hot pot from the government, which was really… that was a delicious meal. I’ve never eaten so well as in Korea, for all cuisines. I’ve had probably my best French meal there, my best Italian, my best Japanese, Chinese, Korean, high/low, street food, fancy. That is just a remarkable culture for eating.

You’ve been talking about eating as a communal activity, but say you’re home alone: What would you make for yourself?

MW: Totally by myself?

Totally by yourself.

MW: Completely by myself?

All alone.

MW: I would make a telephone call to a local eatery. Or I would go to a local eatery. I love eating in restaurants alone.

What is it about it that appeals to you?

MW: If it’s a place that has paper, you can draw. If not, you read your book. Most of my job is watching people, so it’s a good opportunity to do that. And you don’t have to do the dishes.