Life

The Moms Who Fear Child Sex Trafficking More Than COVID

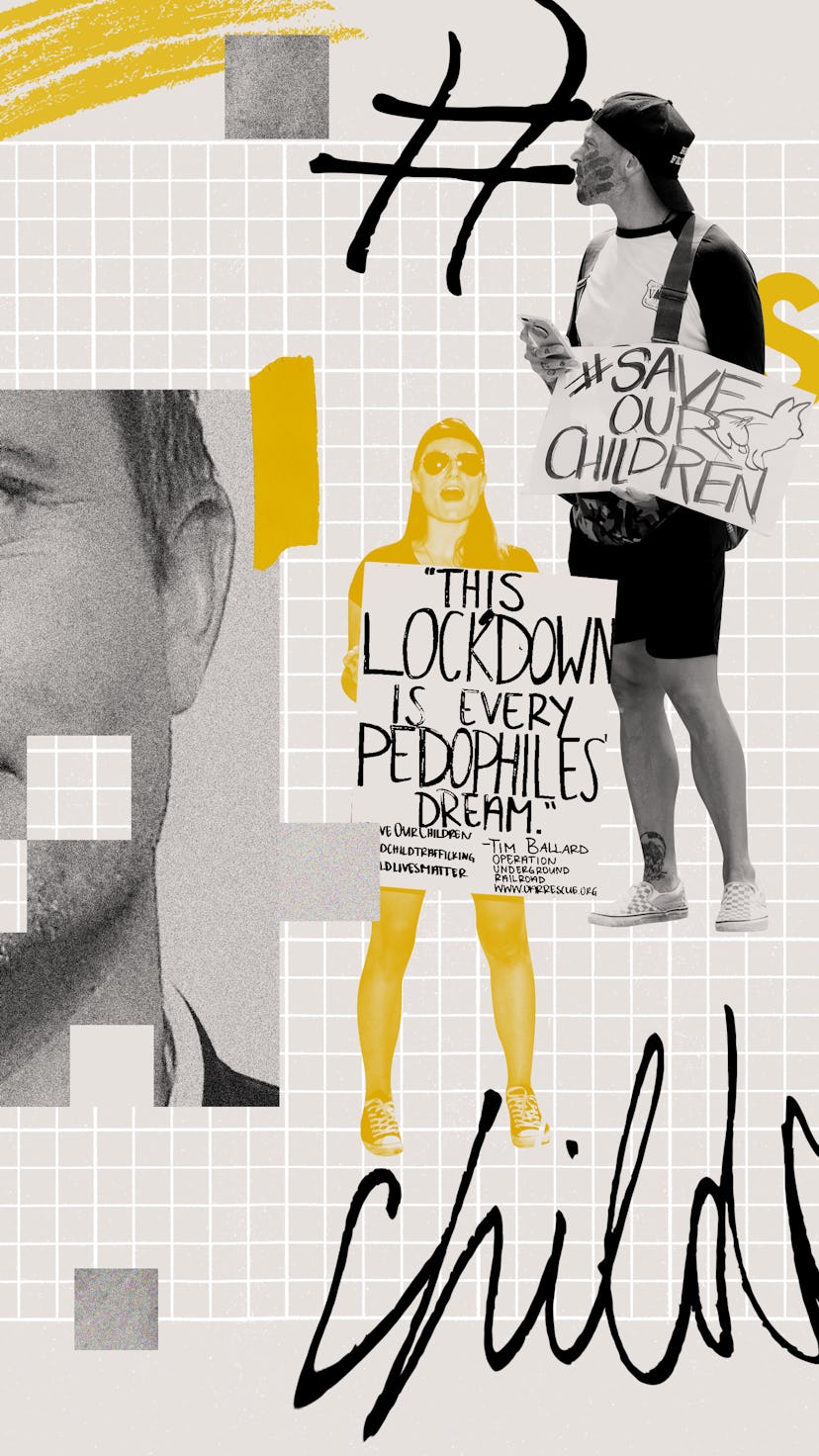

QAnon and lockdowns fueled an explosion of fears that American children are being forced into sex slavery. One organization stood to benefit.

Before the pandemic began, Danielle didn’t think much about child sex trafficking. Living with her husband and four children in Orange County, California, her life, as curated on Instagram, seemed pretty perfect. She worked part time as a consultant for the cosmetics multi-level marketer Rodan and Fields, co-owned a cryotherapy salon, and had a large network of friends, many of whom were wealthy. But now she has a passion: Rescuing the tens of millions of kids that she believes are kidnapped every day and sold into sex slavery across the world and, she warns, “right in our backyards.”

This dramatic shift in focus grew out of the difficulty of parenting through COVID, Danielle’s sense of her relative good fortune, and her fears for more vulnerable children. “I'm a pretty good parent with patience. But I was home schooling during the pandemic and losing my mind,” Danielle said in November. “I was like, I can’t imagine these bad parents, or these parents with little patience, or who are super stressed out over finances, also having to do this with their kids right now.”

Of course, she wasn’t the only one arriving at new realizations during the summer of 2020. Social life had been largely reduced to scrolling: group texts, Facebook groups, Instagram communities, and hashtag-based activism. Some posted black squares to their Instagram pages; Danielle “fell down a rabbit hole” of information online about child sex trafficking. In July, as false allegations spread that the home goods site Wayfair.com was a front for the international child sex trade (to be absolutely clear, it is not), the use of the hashtag #savethechildren began to spike on Facebook and Instagram. Adherents of QAnon, a set of loosely connected far-right conspiracy theories, had hijacked the name of the century-old children’s rights nonprofit Save the Children to disseminate jarring and innacurate statistics about child sex trafficking. Then the same statistics and hashtags also started to appear outside of QAnon circles, in posts from influencers like eyebrow entrepreneur and conspiracy theorist Maddie Thompson, who has 39.9 million Instagram followers, and The Wonder Years and Hallmark channel actor Danica McKellar.

The more Danielle researched within her social media sphere, the more concerned she became. And the more she posted, the more she found herself in an online community of like-minded women looking beyond the borders of their well-manicured lawns. Their fight against child sex trafficking — presented to them as a rampant scourge of criminals seeking to lure children into commercial sex and pornography — is a moral calling, an unpaid vocation, and an entree into a new and intense social circle.

Many of the women who shared the pastel, mom-washed #savethechildren posts weren’t aware that they were spreading Q propaganda. But even those, like Danielle, who know and disapprove of the affiliation say it doesn’t detract from the work they’re doing. “You have to take all that stuff with a grain of salt,” says Danielle about QAnon. “My focus is the facts and the statistics. And the statistics posted up [by organizations I follow], those are true. My take is that the numbers are probably worse, but the other crazy stuff? I have no idea.”

“It doesn't matter if there’s 10 kids or 10 million kids. So what you’re saying about the numbers being inflated or whatever, that doesn’t really matter to me because our awareness should be raised because it’s a problem.”

The statistics she shares — that there are 10 million child sex slaves worldwide, 300,000 children are at risk of being trafficked daily in the United States — have been repeatedly and publicly debunked by NGOs, university researchers, and federal law enforcement. But Danielle doesn’t see any risk in overstatement. “It doesn't matter if there’s 10 kids or 10 million kids,” she tells me. “So what you’re saying about the numbers being inflated or whatever, that doesn’t really matter to me because our awareness should be raised because it’s a problem.”

Supporters of the anti-trafficking movement who came to the cause through #savethechildren have parachuted into a complicated human rights and social justice issue with a commendable but simplistic belief: They can stop child sex trafficking by putting their money where their memes are. At least, that’s what Tim Ballard, the founder, president, and former CEO of the Utah anti-trafficking rescue group Operation Underground Railroad, has led many of them to believe.

Ballard, 45, describes himself as a former employee of the Department of Homeland Security and the CIA. A Mormon and father of nine children, including two he adopted from Haiti, he has devoted himself to fighting sex trafficking full time since 2013, when he founded Operation Underground Railroad. Over the summer of 2020, he emerged as the star of the child sex trafficking panic. As the Wayfair hoax took off in July, he released a video alluding to it, which has been viewed millions of times, claiming that “children are sold that way” and that “law enforcement will get to the bottom of it.”

Since then, the organization has publicly stated that it does not welcome or support QAnon and that it thinks conspiracy theories harm its cause. But, at the time, Ballard told viewers that child sex trafficking is a growing global crisis and encouraged those watching to join Operation Underground Railroad’s (also known as OUR) Rise Up and Get Loud day of protest and rallies on July 30, the World Day Against Trafficking in Persons. “It’s a real day,” he said in the video. “You can look it up.” Like a ruddy, muscled pied piper, Ballard invites viewers to join his mission — one he could only embark upon outside of the bureaucratic red tape he’d faced within the federal government — to raise awareness of what he calls “the fastest-growing criminal enterprise in the world.”

Danielle was all in. On July 30, she attended an OUR rally in Orange County with her husband. Her sign read, “46 kids go missing every day.” Her husband’s sign said, “Adults are raping children!!! Are you uncomfortable?” In her caption on Instagram, she referred to it as “a life changing day.”

She and her husband later held a gala in their backyard to support OUR, themed around the organization’s signature color. “We did yellow uplighting,” Danielle says. “My mom came through and planted yellow flowers all throughout the backyard. We did bracelets that said ‘Rise up’ for the girls and OUR. T-shirts for the men. The food was amazing. It was filet and salmon. Local companies donated almost everything. We charged $450 a ticket to come. But every dollar of that went straight to OUR.”

Asked whether the organization had seen an increase in fundraising last summer, an OUR spokesperson says that “because the 2020 books haven’t been closed, we are unable to comment on fundraising/spending for the year.” In its most recent annual report, OUR says it grossed more than $20 million in 2019, and that 85% of funding goes toward missions, broadly outlined as assisting in the arrest of “hundreds” of traffickers internationally, placing Ukrainian orphans in adoptive families before they could “fall prey to traffickers,” and, in the United States, “facilitating the national deployment” of police dogs trained to find hidden hard drives that might contain child pornography.

Taryn, 29, also attended a Rise Up rally on July 30. She wore a hat with the OUR logo and an #EndHumanTrafficking T-shirt knotted at her waist. “There has never been a time where there have been more slaves than there are today,” she wrote on Instagram. “Millions of people are sold. Millions of children are sold. A child is sold every 30 seconds for sex, labor, organ harvesting, etc. It’s time to stand up and stop it! The brighter the light, the harder it is for the darkness to hide.”

Taryn mostly posts about fitness, life with her husband and small son, and personal empowerment. She’s also posted about her struggles with miscarriages and about her son’s preference for “mommy dolls” — Barbies with long blond hair like Taryn — over trucks. Utah-based and Mormon, she says her family members don’t all approve of her son’s nuanced gender expression, but she and her husband embrace it. “I didn’t always feel loved growing up,” she told me on the phone last fall. “At the end of the day, I don’t care about anything but him knowing he is loved unconditionally.”

Taryn first learned about child sex trafficking long before the #savethechildren frenzy. In 2016, she attended a screening of Ballard’s documentary, The Abolitionists, which was funded in part by Glenn Beck. (An updated version has since been retitled and re-released as Operation Toussaint; it streams on Amazon.) The film depicts Ballard embarking on an operation in Haiti, where he and his “jump team” of civilians pose as men looking to buy children for sex. Once they’ve negotiated a deal, the men swoop into hotel rooms and orphanages, outfitted like military commandos, alongside local law enforcement.

OUR says it has rescued 4,000 people and partners with local organizations to provide housing and psychological care for the victims, but reporting by Vice has found little concrete evidence to support these claims, and it’s unclear whether adult sex workers swept up in the raids face criminal charges. “These ‘jump teams’ go into bars and nightclubs and ask for younger and younger girls,” says Vice reporter Anna Merlan. “It’s likely they’re not breaking up existing trafficking rings but actually creating a demand.” A spokesperson for OUR says the organization does all it can to avoid creating demand or enticing people to commit a crime: “We are clear: They either have what we are looking for, or they do not.” However, the organization wrote in an email statement, “In the early years of OUR’s existence, there were a few instances where some working in our organization’s name did not adhere to our best practices and policies. We cut ties with these individuals and they no longer have affiliation with us.”

In countries like Haiti, where Operation Toussaint takes place and where infrastructure has been profoundly destabilized by natural disaster and corruption, the Rambo-style rescues that Ballard promotes risk forcing women and children out of their living situations, however dire they seem, and depriving women of any means of financial support, which might include adult consensual sex work. Haitian and U.S. human rights advocates have long argued that independent community-building projects and sustainable, grassroots efforts that address local agriculture, access to education, and maternal and pediatric health care would reduce the need for survival sex work and trafficking by creating other local opportunities. But these projects also take years of dedication and communication within the community.

Still, the emotion and urgency Ballard brings to his narrative of child trafficking can be convincing. “The movie was very touching, and we were sobbing the whole time,” Taryn says. “A couple months later, I was competing in a local Crossfit competition where all of the proceeds were given to OUR. Tim was there, and he came and spoke. He and my husband kind of clicked. I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I've seen his documentary. Jeremy, we have to get involved. We have to do something.’"

Taryn and her husband started attending OUR fundraisers, talking to Ballard as much as they could. “We just wanted to get our faces out there and be donating as much money as we possibly could just so they took us seriously that we really wanted to be involved.” Eventually, Taryn and her husband made a five-figure donation to OUR, a large sum of money for them. “And after that, they started taking us seriously.”

When her husband accompanied OUR on an operation, Taryn, who mourned deeply the pregnancies she’d lost, felt like they were doing something to help other children in pain. For them, that was worth more than money. She believes Ballard when he says OUR is ending modern day slavery — he draws comparisons between himself and Black American abolitionists like Harriet Jacobs — and saving children from rape, abuse, and torture.

Ballard’s pitch to parents seeking a higher purpose is all the more powerful due to the difficulty of accurately quantifying the problem of child sex trafficking — and thanks to a broad misunderstanding of what child sex trafficking looks like. U.S. legislation in 2000 defined it as “the act of recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing, obtaining, patronizing, soliciting a child for commercial sex, including prostitution and the production of child pornography.” While funding and legislation has been directed at stopping these crimes, “there is a gaping hole in our knowledge and understanding of human trafficking,” says Caren Benjamin, the chief communications officer at the anti-trafficking nonprofit Polaris.

The most commonly circulated statistics have been extrapolated from flawed studies. For example, “300,000 children at risk,” persistent on social media, stems from a 20-year-old report; the study’s own authors, Richard J. Estes and Neil Weiner of the University of Pennsylvania, say it’s no longer relevant. In 2015, the State Department told The Washington Post it no longer uses any numbers derived from the 2005 International Labour Office report on human trafficking, but OUR references it in its literature and on its site.

The Polaris-run National Human Trafficking Hotline, along with the hotline run by the Center for Missing and Exploited Children, offer the largest and best-known collection of reports about minors being trafficked for sex and labor in the United States, but Benjamin says even this data is deeply flawed. “Because communication is incoming only, there’s a tremendous amount of demographic information and real numbers we just don’t know,” she says. Each call is reported as a separate incident, even if one person calls multiple times or a bystander reports a faulty tip, which happens more frequently as misinformation fuels awareness online. A 2019 Polaris study puts the number of known trafficked children in the United States at “22,326 individual survivors; nearly 4,384 traffickers; and 1,912 suspicious businesses.”

More difficult than correcting statistics is countering the narrative popularized by #savethechildren: very young children, stolen from homes and parks, held prisoners in dark, dirty hovels. According to the FBI’s 2019 missing persons records (where the “circumstances” field is optional and used by police about half of the time), stranger abductions count for about 0.1% of missing persons in America; noncustodial parent abductions account for another 0.8%. Ninety-five percent of missing persons are classified as “runaways.”

Meanwhile, the trafficking of minors for the purposes of sex does happen frequently in America, but it typically comes to light when a trafficked child winds up in the adult criminal justice system. Cyntoia Brown was convicted of murdering her alleged trafficker when she was 16 years old. She spent 15 years in prison before her cause was picked up by celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Rihanna, and Brown was granted clemency. In Kenosha, Wisconsin, 17-year-old Chrystul Kizer was charged as an adult in the murder of Randall Volar, a 34-year-old man who had been arrested and released on charges of trafficking and child pornography. The images seized from his home show Volar sexually abusing Kizer and other Black girls, according to the Kenosha Police Department and district attorney, but Kizer has not been able to present the evidence as a mitigating factor in her trial. Zephaniah Trevino, then a 16-year-old Dallas teenager, was with her then-18-year-old friend — whom her family alleges was trafficking her —– when the friend shot and killed another 24-year-old man. Zephaniah is being charged as an adult for her role in that murder. (The 18-year-old’s lawyer does not dispute that he was the triggerman; he does deny the trafficking claim.)

But these stories don’t comport with the version sold by #savethechildren. In the vast majority of child trafficking cases, there are no chains, there is no shadowy predator stealing into the virtual bedrooms of suburban girls scrolling TikTok late at night. Most trafficked minors are from a vulnerable population: the poor, the undocumented, the drug dependent, LGBTQ teens, mothers escaping abusive relationships, unhomed young people seeking a place to sleep for the night. These victims don’t seek out the help of groups like OUR that work with law enforcement because chances are high that a trafficked teen will be arrested, not rescued.

“Arrests and convictions create a revolving door for survivors,” says Melissa Sontag Broudo, the co-founder and co-executive director of the sex worker harm-reduction advocacy group the SOAR Institute. “They are constantly re-victimized and defeated in moving forward with their lives due to their record, and thus staying in the industry may be their only option. Traffickers also know this and utilize criminalization to their advantage to prevent mobility.” Sontag Broudo has advocated for a bill in the New York Senate that would vacate the criminal convictions of trafficking survivors.

Michael Hobbes, a journalist and co-host of the podcast You’re Wrong About, has studied the rise of child trafficking narratives in the media extensively. “All moral panics blend real societal problems with the cartoon version,” he says. “They blend the solvable with the extreme. These types of crimes — kids in dungeons, thousands of children being abducted by strangers — are just vanishingly rare. And prioritizing them doesn’t help kids who are actually at risk. It doesn’t fund domestic violence shelters or support LGBTQ youth. You’re not stopping anything. But you are ‘getting the bad guy,’ which is very satisfying to some people.”

In the world of #savethechildren, the good guy who gets the bad guy is indisputably Tim Ballard. In addition to his role as leader of the children savers of Instagram, he’s a frequent guest on Fox News, has spoken at companies like Google, has been the subject of laudatory stories in publications like Rolling Stone, and has had his operations praised on CBS Evening News.

In 2017, the Trump administration made Ballard an unofficial adviser to Ivanka Trump’s anti-human-trafficking initiative, an effort that was widely criticized by many reputable anti-trafficking organizations, including Polaris. Ballard is a vocal supporter of the Border Wall; he wrote an op-ed for Fox News titled “I've fought sex trafficking as a DHS special agent — We need to build the wall for the children.” According to Vice, Ballard misrepresented the story of one Mexican migrant child trafficking victim on multiple occasions in order to advance this policy, including in written testimony before Congress. Ballard allegedly lied about the victim’s age and that she’d been rescued in New York City by OUR-affiliated organizations when, in fact, she’d left on her own. (OUR spokesperson: “Unfortunately, we have come to understand Vice’s agenda-driven objective is to comb through years of information to find any, even minor, discrepancy, and to twist anything found into a negative portrayal of an honorable organization.”)

In October of 2020, Troy Rawlings, an elected Utah prosecutor, announced that OUR was under investigation. His office could not comment on the specifics of the investigation but confirmed via phone that, in general, it concerned a law that prohibits nonprofits from making false statements in order to solicit funds. “If asked, OUR will cooperate fully with any official inquiry into its operations,” the OUR spokesperson says.

A few weeks before Rawlings’ investigation was announced, I attended an OUR rally in southern New Jersey. I signed an agreement that any signs I created wouldn’t show inflammatory images or corporate logos, a seeming reference to Wayfair and other corporations QAnon has baselessly accused of child sex trafficking. The rally took place in the small town square of Pitman, New Jersey, where a sparse and sweaty crowd had gathered. OUR’s broken chain logo was on display, but the speakers were all independent of the organization. Among them was a Gloucester County detective who, as part of the Special Victims Unit, is responsible for interviewing all children, from infants to age 17, who disclose incidents of sexual assault. She spoke about the major risk factors for child trafficking: being runaways, children with a history of abuse or drug dependence. She stressed that most trafficked children and teens are under the control of a person they trust, like a boyfriend.

Can a less lurid narrative of child sex trafficking sustain the interest of the #savethechildren crowd? When Danielle and I spoke again in March, she said that while she still supports the mission of OUR, she’s turned most of her energy to promoting the work of Dr. Sandra Morgan. Morgan, who co-chaired the Trump White House’s Advisory Council to End Human Trafficking with Ballard, heads up the Global Center for Women and Justice at Vanguard University, a private Christian college in Southern California. “I’ve learned a lot of stuff because of Dr. Morgan,” Danielle tells me. “I know that, here at least, it’s less about stranger danger and more about education and prevention at home and in the schools and churches.”

“When we were in lockdown, everything on social media was so hyped up,” she continues. But the shock value of #savethechildren is what led her to her current work. “That stuff raised so much awareness. I wouldn’t have changed anything.” She’s putting together another fundraiser, this one for Morgan’s organizations. It will be a Mother’s Day shopping event and will be held, like the OUR gala, in her Orange County backyard.

This article was originally published on