Coronavirus

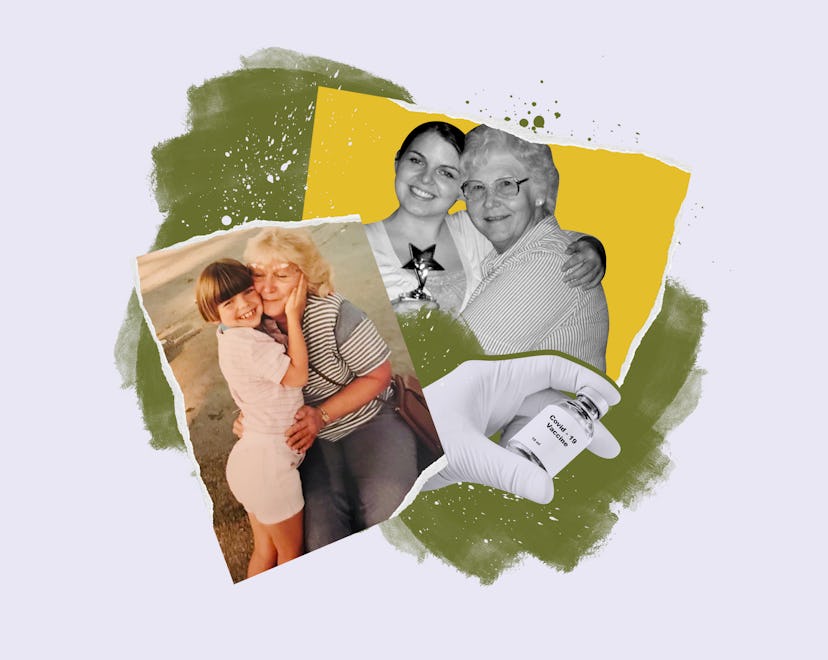

I Just Want My Granny Jo To Get The Vaccine

I had no idea how much anxiety I was holding in my chest about her health.

It was May 2020 when I saw my grandmother for the first time since Christmas 2019. We had missed Easter, her birthday, and all of the great-grandchild picnic lunches and ice cream trips and Sunday afternoons discussing tulips and hydrangeas in between. I saw her at an outdoor, drive-by birthday celebration for my nephew, and while I wanted to hug her and squeeze her, I didn't. I felt like a bomb that might blow up the minute I got too close, like I could infect her with coronavirus just by looking at her. Like my very thoughts were infiltrated with germs and if I dared to say them out loud, they would just turn her into dust like in Avengers: Endgame.

She sat on a chair outside of my brother's garage, and I positioned myself a good 20 feet away. We talked about digital learning, and she told me how worried she was about the kids. I assured her my girls were OK, that they missed their friends, and that I really missed grocery shopping. "I have to turn off the news," she said. "I can't watch it anymore. It scares me." She had just turned 83. Of course it did. It scared me, too.

Since then, every decision our family has made has been based on the safety of Granny Jo. Granny Jo, who taught me to sew on the Kenmore my grandpa bought her for her first Mother's Day in 1958. Granny Jo, who taught me to plant tulips, who introduced me to Shirley Temple and The Wizard of Oz, who will go on every single rollercoaster you wanted at Six Flags, but shut her eyes the whole time. She taught me how to throw a dinner party after I begged her to host one — the tub of Country Crock has to be in the middle of the table — and the family cookbook she made for me and all of her grandchildren when we each got married is one of my prized possessions.

In August, when it was time to decide if my 6-year-old would be going to first grade in-person or via Zoom, all I could think about was Granny Jo.

She is my measuring tape, my compass. How did Granny decorate the Christmas tree when she had a toddler who grabbed everything? (She reminded me that ornaments can be replaced.) On my long, hard, exhausting days last spring, I wondered if Granny ever had nights where she left the kitchen a mess and went to bed. (She didn't, she told me me. "But I didn't work as hard as you do," she said, to make me feel better.) I use the quilts she has made me to make a pallet on the floor like she did for us, and I tell my girls, "This is exactly how Granny Jo used to do this." And then I make us all popcorn, because Granny would do that, too.

In August, when it was time to decide if my 6-year-old would be going to first grade in-person or via Zoom, all I could think about was Granny Jo. If I enrolled my daughter, would we be able to see Granny at all? How could we still have her over for Thanksgiving if we took this risk of school? When I hear that my Granny has seen other people who think the pandemic is a hoax, I am furious. What are they doing? What if they make her sick? What if they kill her? She once printed out stories I wrote in the sixth grade and folded them up in her pocketbook and took them to church to pass around to everyone. When I met these church members later, they all squeezed me and said, "Your granny is always so proud of you. She's always telling us how smart you are."

My 2-year-old has her eyes. She taught me to swim. She was born in 1937, and I make her tell me the story of where she was when JFK was assassinated over and over. (In a Rich's department store. There was an announcement over the PA system and she couldn't hear what they said, but everyone started screaming, so she just picked up my 3-year-old dad and ran like hell out the front door.) She used to make meatloaf for family dinners, and because I didn't like it, she'd then drive all the way to McDonald's to get me a 10-piece McNuggets meal to eat with my mashed potatoes.

As the holidays got closer this past year, I panicked. I sent a lot of texts to family like, "Please be careful," and "We don't want to get Granny sick, y'all please be careful and wear your mask." My dad works retail, and he worried constantly about bringing it home to her. He told me how much she missed the kids, how she was feeling lonely. Granny told me she missed church, that their services were all done in the parking lot while everyone stayed in their cars. I was devastated to miss Black Friday shopping with her, a tradition we've held every year since I was 10, starting at 5 a.m. outside of Macy's. "This used to be Rich's," she always tells me, still salty about the loss of her favorite department store.

As she pointed out, what is the point of living to be 83 if you can't see your great-grandkids?

When I left an emotionally abusive marriage with my 2-month-old daughter, Granny was one of my biggest supporters. She took me shopping, she bought my baby her first pair of shoes, she cooked me dinner. That first Christmas, I scraped together money from odd jobs to buy my baby some Christmas pajamas and her first ornament, and then I went straight to Granny's house. She rocked my girl to sleep and let me decorate her tree all by myself. "I have to turn off the news," she said in May. "I can't watch it anymore. It scares me."

There was no way to ask Granny to be completely on her own from March until now. I knew that, and I didn't want it for her either. As she pointed out, what is the point of living to be 83 if you can't see your great-grandkids? So we took precautions. We hemmed and hawed over decisions. We took risks we felt comfortable with, all because we kept thinking of Granny Jo.

And then there was a chance for her to get the vaccine. A county Department of Health sent out Facebook posts about drive-through vaccinations — no appointment needed! My dad planned to take the day off, reworked his schedule so he could be one of the first in line at 7:30 a.m.

I wept with joy. I felt such immense relief. Until he called me at 8:00 a.m. that day and said they were turning people away. "They changed it overnight. The cops here say we have to make an appointment with the Department of Health now." He called over and over. When he finally reached someone at 8:30, they said there were no more vaccines. "They're all full," he told me. And I felt a fresh rush of anger and dismay and frustration at our administration, at this botched vaccine plan, at all the people who are putting Granny at risk. Granny with her love of scary movies and her plastic bonnet she wears over her hair when it rains and her cornbread recipe.

So now, I wait. And I refresh Department of Health websites and I call pharmacies and I put her name on the waiting list. "1937," I say when they ask me what year she was born. "Two years before The Wizard of Oz came out." The emails that tell me the waitlists are full offer helpful "tips." Like continue social distancing, and wear a mask, and avoid crowds. But they don't say anything else important. They don't offer easy ideas on how to quell the wave of anxiety crashing and cresting in your chest when you hear that your granny went to Food Depot to pick up flour and sugar because she's bored and wanted to make her famous black walnut cake. They don't give any tips on how to navigate a 6-year-old's desire to spend the night with her Great-Granny Jo and your fear that it'll be the most dangerous slumber party ever. They don't have any advice on what to do if your granny is tired of watching Little House on the Prairie repeats because she's scared to switch to the news.

But, you know. She's on a waitlist.