Life

A Hallmark Of The Panic Years: The Day You Find Out Your Best Friend Is Pregnant

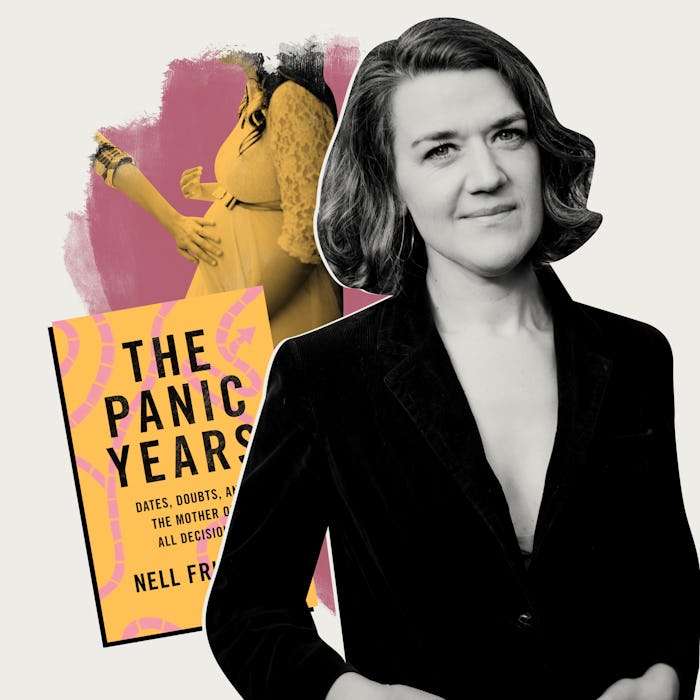

Author Nell Frizzell on the absolute mindf*ck of your friends having babies.

Unless you have the mixed blessing of becoming the first person you've ever met to get pregnant (in which case, congratulations, commiserations, better luck next time), one of the unequivocal hallmarks of the Panic Years is the day you find out one of your good friends is pregnant.

I say "good friends” because, of course, other people get pregnant all the time. These pregnancies mean about as much or as little as somebody else's new shed. But it's one of your best friends, one of these women who can be traced through your bone marrow like stem cells, one of the women who knew your grandparents, with whom you shared your first cigarette, and whose clothes you used to borrow for years at a time: When they tell you they're having a baby, it's like opening a whole new chamber in your heart. It hurts, it stops your breath, your whole life flashes before your eyes, you get a pounding in your chest, and you need to sit down. Of course it's wonderful. But it can be other things, too.

When she told me she was having a baby, I think it's fair to say I handled it the way any 12th-century peasant handles news of the Black Death.

For instance, after finding out that my friend Alice was pregnant, I went home and howled into my pillow for nearly an hour. I was a snapped twig of self-pity, fear, maternal hunger, jealousy, and rage.

I had known Alice since we were teenagers, and in the intervening years, we'd not only lived together but, at one point, spent every single day in each other's company for more than 12 consecutive months. I have never before or since met anyone I could so happily and easily coexist with. For a few years in my 20s, she was as intrinsic to my life as my own breath and blood. I called her my wife. She called me wifey.

So that day, when she told me she was having a baby, I think it's fair to say I handled it the way any 12th-century peasant handles news of the Black Death. I wept. I lifted her top to look at her skin. I felt my rectum flutter in panic. I suddenly got a vision of lying in my garden, aged 16, studying for an exam with Alice while listening to Marvin Gaye, and realized it was all over. I felt my armpits go slick. I wanted her to become unpregnant. I wanted to be pregnant, too.

Suddenly, ambivalence about children seemed like cruelty. Alice’s husband loved her so much that he wanted to bind his actual DNA to hers. He wanted to create a future life, an entire person, within her body. He wanted her to be tied to him, to rely on him, to be his family forever. Why did none of the men I’d been with understand what pregnancy meant to me? I screamed and sobbed into that bedding for my lost 20s, for envy, for my failure to ever find a man who wanted a family, for terror at how fast life was happening all around me, for the weight of this decision I was going to have to lug around behind me forever.

Women are taught (by popular culture and convention) that pregnancy should be a source of joy. When a friend reveals her news, we are meant to swell with pride and excitement. We are meant to throw ourselves into knitting, baby showers, and, of course, shopping. And yet, ask any real-life woman how she reacted when one of her best friends first admitted they were pregnant and it soon becomes quite clear that the announcement is, in fact, a focal point of panic, nostalgia, grief, longing, uncertainty, and confusion, too.

“I felt immediately like I’d missed the grown-up lecture and was flailing through life,” one woman tells me, via Twitter. “I went to get my first tattoo that weekend, feeling that if I wasn’t in the settled-with-baby group, I had to somehow appear wild and free.”

“I am genuinely over the moon for my friends,” adds another, “but it doesn’t take away the sadness that I’m becoming this kind of strange Peter Pan figure as I still go to gigs, go on holiday, and don’t have as much in common with everyone in the group.”

Looking back, I can see that, yet again, I was using “a baby” as a catchall for a lifetime’s desire for stability, love, security, the ability to rely on a man without driving him away, the chance to right the wrongs of my childhood, affection, and permission to be vulnerable. But beyond that, I was also, genuinely, hungry for the weight of a child in my body, to give birth, to confront the blood and pain of that transformation and come out with something magical, to give myself over utterly to something and somebody else, to breastfeed, to be called “mum,” to hold someone’s arms, at knee height, as they walked through a garden, to kiss the underside of their chubby cheeks, to be swollen with milk and pride and oxytocin and purpose, to change nappies, to feel a baby kick beneath my ribs, to look down at a sleeping face and know that it had come from my body and my partner’s body and our love.

We may know, rationally, that love, commitment, and babies are not a finite resource to be doled out on a first-come-first-served basis. But to know it emotionally is another matter.

Apart from the gear-change of maternal hunger that a friend’s pregnancy can evoke, “the announcement” can also feel like a robbery. Another person’s pregnancy can feel like the loss of yours— however theoretical your own pregnancy may have been. You may feel jealous, wrong-footed, betrayed, that someone you loved and trusted has jumped ahead.

Even when the resources are intangible and immaterial, the capitalist instinct remains: we go through life feeling in competition for love, relationships, respect, approval, health, fertility, a sense of belonging. We may know, rationally, that love, commitment, and babies are not a finite resource to be doled out on a first-come-first-served basis. But to know it emotionally is another matter.

“For me, it’s gone from, ‘Shit, are you going to keep it?’ ten years ago, to now: smiling through gritted teeth and saying congratulations and offering to babysit while simultaneously feeling I will break with sadness,” one woman tells me anonymously on Twitter. “And oddly enough it’s not so much the fact of a baby on the way that I envy so much as the certainty and security of a couple deciding together to share something so momentous. Being single and without children means pregnancy announcements create even more distance between me and my closest friends.”

I know that distance. I have poured my envy into that distance. I have wailed into that distance. You may have, too. Even for women who are more sanguine about the prospect, a best friend’s pregnancy can still bring the question of babies bobbing, unwanted, back up to the surface.

In my head, we were still all just playing at grown-ups, talking about it speculatively, testing the water before “really” settling down.

If the average age for a British woman to have her first child is 28.8 years old, it is, I suppose, faintly ridiculous that I was shocked to learn that my 31-year-old friend, Alice, was having a baby. This wasn’t a teenage pregnancy; I already had a couple of gray pubes. But the fact that we were slap-bang in the middle of the baby-making window didn’t alter the fact that, somewhere in my heart, we were all still the group of 17-year-olds who drew heavy unibrows across our faces to go to an eighties party dressed as Madonna. In my head, we were still all just playing at grown-ups, talking about it speculatively, testing the water before “really” settling down.

But once one of your contemporaries has a baby, the truth is harder to ignore. Time is passing, chapters in your life come to an end, and your 20s are a decade, rather than a way of life. When Alice told me that she was pregnant, it suddenly seemed that I was being given license to want the same thing. I was no longer the secretly broody outlier in the group—my desire had aligned to that of at least one of my friends, not to mention her partner. If she could do it—could put her career on hold, take the hit to her relationship, stop going out, and start spending her evenings googling rashes— then surely I could too?

A study from the Bocconi University in Italy and University of Groningen in the Netherlands using the data of 1,170 women, of whom 820 became parents during the study period, found that after one of the women in each friendship pair had a baby, the likelihood that her friend would also have her first baby went up for about two years, and then declined. In short, once one of you gets “in trouble,” there is a temporary spike in friends following suit.

The two researchers leading the study put this down to a combination of factors: social influence, also known as good old-fashioned peer pressure; social learning, i.e., once you’ve seen someone close to you wrestle with sleep deprivation, mastitis, croup, and crawling, you feel more able to embark on them yourself; and finally cost-sharing — if you’re going to have a baby, why not do it while those around you can share the burden of childcare, get their children’s secondhand clothes and old toys? To this list, I would also add the matter of emotional permission.

As the renowned professor of philosophy and cognitive science at Yale University, L. A. Paul, argues, you cannot know what the experience of having your own child will be like until you experience it. You cannot judge accurately whether the experience will be positive, negative, or somewhere in between; it is impossible to judge as a hypothetical. And so into that vacuum and onto the pregnancies of your closest friends, you pour all your anxieties, hopes, and disquiet. Their experience becomes a yardstick against which you can speculate about your own decision. That might mean a hardening against the prospect of babies, an acceleration in your plans to start trying or, simply, downing a bottle of wine and screaming into the abyss until the panic starts to fade.

But do try to remember that nobody ever got pregnant just to make their best friend feel like shit.

The greater part of how you react to a friend’s pregnancy will depend on your own circumstances. When I was single, friends’ pregnancies turned them temporarily into strangers, embarking on a life that shared little with my own. When I was in an established relationship, the pregnancy of a peer acted as an emergency flare, burning in the sky above my head for days, forcing the baby question into my immediate field of attention, blinding me to rational argument, lending the prospect a kind of urgency that I internalized while my partner simply pushed it from his mind. When my son was small, I greeted each friend’s new pregnancy with joy and a deep-felt sense of sisterhood unlike anything I’d really known before. Now that I have a baby, have my period back, and am frequently being asked if I’m going to have another child, I’ve started to feel the same old creeping envy, sadness, and anger whenever I hear that one of my contemporaries is up the duff. How can we stop seeing other women’s lives as a comment upon our own? How can we learn not to compare ourselves to others around us? How do we take the sense of competition out of the sisterhood? If I knew that, my friends, then believe me, I would tell you.

Don’t reproach yourself if that realization elicits panic, nostalgia, fury, disappointment, hiraeth, or confusion; your feelings are your feelings and the only way to deal with them is to accept they are real and temporary. But do try to remember that nobody ever got pregnant just to make their best friend feel like shit. Chances are, they weren’t even thinking of you at all.

You can buy Nell Frizzell's memoir, The Panic Years: Dates, Doubts, And The Mother Of All Decisions on Bookshop.