Our Pandemic Year

Becoming Baba: On Transitioning During A Pandemic When You’re A New Parent

Returning to some semblance of normalcy has only affirmed the choice to change, to become, to make public what only recently came fully into my own private consciousness.

If you call the Social Security office in Florence, Kentucky, there are some helpful human angels doling out acts of bureaucratic kindness when they’re not eating lunch, and they tell me that I became Andrew August Rich on Feb. 9, 2021.

But this story isn’t linear — far from it. There hasn’t been a way to arrange the identities, to sort the pieces of this narrative, even in my head, in a way that felt true. A few weeks before being recognized as myself by the bureaucrats responsible for these intimate legalities, my 1-year-old child — the bright, brilliant, redheaded human who has barely breathed air as long as they lived in my body — deadnamed me.

That is transitioning as a parent during the pandemic, as best I can encapsulate it.

Before pregnancy, and during the 575 days between the bleed that kicked off my pregnancy and when my period finally returned, I thought I loved my menstrual cycle. I was so excited to discover that part of me, of my body — and connecting with my cycle is what led me to realize my nonbinary identity. But as a baba (not, never a mama) my postpartum bleeds have been brutal. Soaking through a pack of pads in a couple of days (pads that feel more valuable now, procured in an hours- or days-long process of online shopping or contactless grocery pickup), caught between gazing at blood clots caught between my legs and chasing after a nearly-walking toddler — that blood is what led me to the doorstep of my transness.

(And to be crystal clear, I am still nonbinary and it took me a few years of naming what and who I am not to find the safety and confidence to name and explore who I am. Nonbinary identity isn’t “trans lite.” This is one trans journey, one gender journey of many.)

My 1-year-old child — the bright, brilliant, redheaded human who has barely breathed air as long as they lived in my body — deadnamed me.

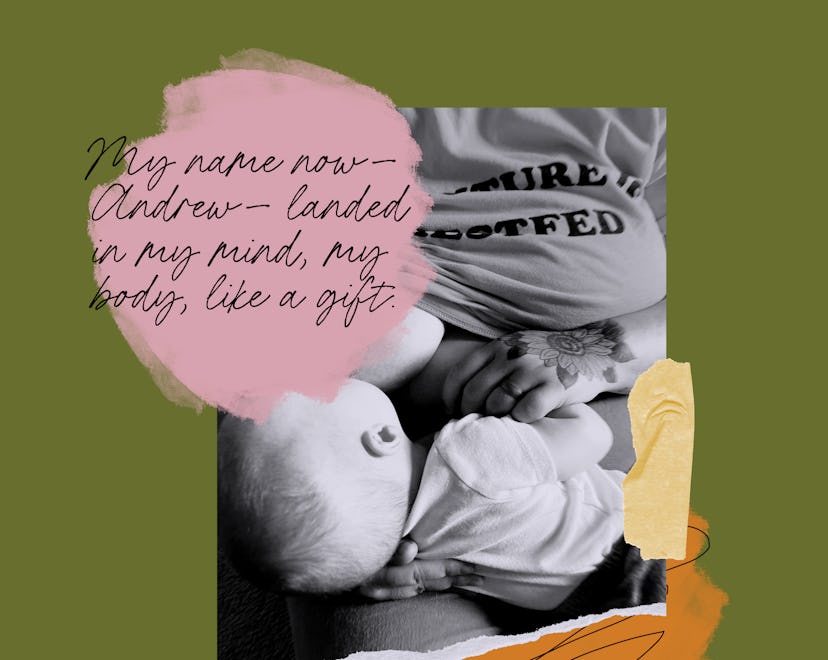

I thought I was fine with my name, too, until I wasn’t. My name now — Andrew — landed in my mind, my body, like a gift. Mid-pandemic I knew it was mine, and chills and hope rolled through my body. But it felt like enough to keep the name in my pocket. To glimpse at that self when I got the chance.

I shared the name with an app or two, knowing it would be there waiting for me when I went to check a horoscope or practice Norwegian (somehow during the pandemic, I made it to 200-something days of Norsk practice in Duolingo, which pales in comparison to my spouse’s 473). And then I started bleeding.

I know I’m not alone in this, that many other trans siblings share this experience, this pain, but all too often, I get misgendered just one — just one — too many times in a day. It can come from anywhere. It might be the people who brought you into this world; it might be an old friend or acquaintance who came across your number and wanted to say hi. It’s often a stranger. It’s often someone trying very hard to help you. But they do it, and then the world falls away, and it doesn’t matter what they meant, it doesn’t matter that they don’t know, it doesn’t matter it doesnt matter it doesn't matter. It just hurts.

That day — the day I started bleeding — it was a guy at the Apple store who nearly made me miss my baby’s school pickup and who kept calling me “that lady over there” to another customer, beaming at his efficiency and customer service.

That’s when I knew I wasn’t fine — bleeding, late, Andrew.

I came out methodically. Facebook post written. Instagram post written, too. Parents, siblings texted. Posts posted. Court prayed to, ordered. Any day now I’ll get a new social security card in the mail, but there’s ice and snow and it’s President’s Day and all incoming mail has to sit for a few days before it’s opened. Hopefully soon I’ll be able to prove it to my new employer.

The most startling part of doing so much transitioning in private, at home, on the internet during the Coronavirus pandemic, is that now — doubly vaccinated in a public facing job at a family health clinic — Andrew is not nearly as visible, as obvious as he feels to me. I am this person, but am ma’am-ed and lady-ed more times than I can count each day. Returning to some semblance of normalcy has only affirmed the choice to change, to become, to make public what only recently came fully into my own private consciousness. At least now, when on the phone for the 20th time in a day and someone mishears me — “Oh, Andrea, hi there,” — I can clear my throat and assert — “Uh. No. Andrew.” — ever grateful for the hard, strong sound of that tiny “double u” as I wrestle with both the transphobia and the muffling effect of masks in my fight to be seen.

I can’t change my gender marker — the pesky, elusive F on my birth certificate — because I was born in Alabama and I have to have “the surgery” to do so. According to an article that came across my Facebook feed the other day, a woman I grew up with — the first trans person I knew — is trying to change that. I hope she can. According to another frenzied Google search after some moments of doom scrolling, “top surgery” “counts” as “the surgery.” But there’s a very good reason I won’t cut my tits off yet and that baby is still learning not to deadname me.

Transitioning as a parent during the pandemic — and before that, trying to avoid said transition — made me realize that I don’t want to have more kids.

Transitioning as a parent during the pandemic — and before that, trying to avoid said transition — made me realize that I don’t want to have more kids. Somewhere after those hazy, gooey days of the fourth trimester, after the world closed, maybe back when the CDC was telling us that we didn’t really need to mask, I slowly rode some unnamed emotional train to the end of the tracks.

And embracing the fact that each moment as a parent, each moment with my child truly is a last, made me sure I wanted to ride lactation out, too. For a while there, my goal felt like four years. My mom had four kids, breastfed us each for about a year; I could just chestfeed this one for four and call it good, right?

I’m not sure, but the State of Alabama won’t call it good — won’t recognize my transness — until I cut something off or sew something on. (I don’t think they know what’s off or on. How little would you like to bet anyone who wrote any of these laws knows about the intricacies of phalloplasty?) And there’s got to be something poignant to say about how absurd it is to ask me to choose between my child’s only (once primary, now well-loved) source of food and comfort and antibodies and, and, and — and a little M on a driver’s license in a different state in the midst of a global pandemic. But when I go to think or write or say it, my thoughts just burn up into those little black, squiggly nothings you see in cartoon strips.

Parenthood, gender, life can only be captured in one particular moment, and then we keep growing and spiraling on.

Parenthood, gender, life can only be captured in one particular moment, and then we keep growing and spiraling on. Just two days after I finished writing this, I got a new-patient appointment with a wonderful doctor who focuses on trans care in Kentucky and I now have a letter that will allow me to change my passport and then my driver’s license, no surgeries required. The system absolutely needs to go, and there are holes and loops and hope and help. (Trans Equality has info on how to change your documents in each state, and my friend, colleague, and doula Eli Lawliet, The Gender Doula, has been immensely helpful in my legal transition process.)

Maybe I’m the poignant sentence, me and this child whose self and gender are still being born in front of us daily, who deadnamed me twice and then finally, blissfully garbled, “ANDREW,” in what sounded like a mouthful of baby teeth and the future — ours — rolling out in front of us.

This article was originally published on