Reading a book 200 times is a surefire way to find out whether you love it or want to throw its rhyming llama couplets into the diaper pail. Children's books especially do a tricky dance for an audience of squinty-eyed parents and wide-eyed tots: the best ones, like a syringe of infant-suspension Tylenol, have a little something for the parent at the end. These are the ones we are celebrating in This Book Belongs To — the books that send us back to the days of our own footed pajamas, and make us feel only half-exhausted when our tiny overlords ask to read them one more time.

When my daughter Sylvie was in preschool, she figured out that I wrote books for a living — and began asking for new stories every night at bedtime. At first, I balked. It was the last thing I wanted to do at 8 p.m., peak hour of parental exhaustion. But my daughter, sensing weakness as only a three-year-old can, eventually ground me down. Soon enough, I was generating, on a nightly basis, the original content my tiny customer demanded.

One evening, when I was particularly fried and couldn’t conjure up a fresh story about pirates or knights, I started telling stories about my girlhood in Pittsburgh, and a neighbor whom I’ll call Danny Reilly.

Danny was easily the naughtiest kid on the block. He wasn’t mean or anything — he just couldn’t say no to a dare, like the time he leaped from his second-floor bedroom window to a tree. Danny also came from a huge, boisterous family, so he was able to get away with, say, not brushing his teeth for five days straight and bragging about it to an admiring circle of kids.

Well. Sylvie was immediately hooked. Every night she begged for more of Danny’s antics. The story of Danny hiding in a vacant lot and setting off a neighborhood manhunt was one of her treasured favorites.

Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! by Mo Willems, $10, Amazon

Eventually I ran out of Danny stories (I had to stop at his teen years, when he became a pyro) so instead, I dreamed up tales of Sylvie’s teddy bear, "Teddy," causing a ruckus while she was at school. I contrived to have Teddy invite all the stuffed animals of her friends over for a wild party, complete with a raucous dance contest, a delivery of 100 balloons, and a chocolate sauce bath. In a climactic scene, the unruly gang of stuffed animals piles the couch cushions into a mountain and slides down the heap using cookie tray “sleighs.” (That last bit was taken from real life, when my daughter and her friends got creative during a playdate in our small Brooklyn apartment.)

As a toddler, Sylvie relished the scene in Olivia when the incorrigible pig painted on the walls. She lived for the tantrum the pigeon unleashed in Don’t Let The Pigeon Drive The Bus.

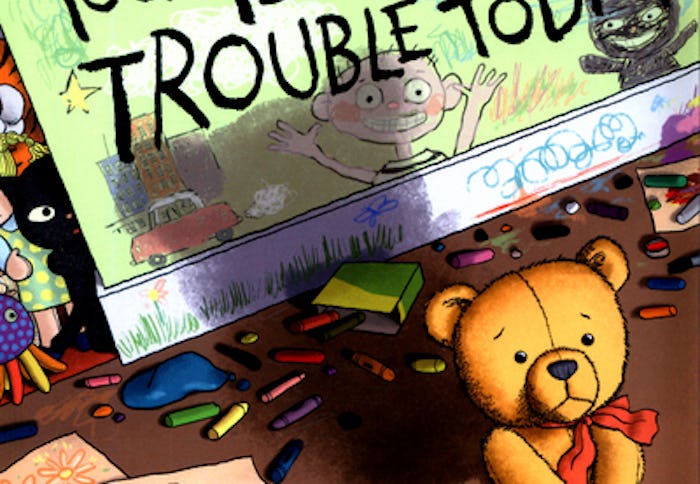

She loved those stories even more, and swore that when she returned home from preschool, her wily Teddy was always in a different position in her room. I eventually turned Teddy’s transgressions into a book (I'm Afraid Your Teddy is in Trouble Today.)

Why are children so captivated by mischievous characters, which have endured in kid lit since at least Huckleberry Finn and Pinocchio? They’ve been a lifelong obsession for my daughter. As a toddler, Sylvie relished the scene in Olivia when the incorrigible pig painted on the walls. She lived for the tantrum the pigeon unleashed in Don’t Let The Pigeon Drive The Bus. She howled when a naked David gleefully ran down the street in No, David!, his frazzled mother in pursuit.

No, David! by David Shannon, $7, Amazon

As Sylvie grew older, she moved on to Roscoe Riley, who starts every book in a time out, and Horrid Henry, fond of making stink bombs (his brother, the bland, fastidious Perfect Peter, is not nearly as popular). She gobbled up stories of Clementine, who spends a lot of time in the principal’s office.

Of course, we need books that teach good behavior, but things would get incredibly boring if every character learns to share, or to clean up their room. Everyone loves a rascal, don’t they? And reading about their exploits is actually helpful for kids, according to Brooklyn school psychologist Jennifer Hope, Ph.D. “In this way, a child can explore the consequences of unacceptable behavior within the safety of a story, without actually suffering the consequences themselves,” she says.

Characters actually do things that all kids think about but mostly don’t dare do.

And children relate to characters that mess up or make wrong choices. There’s a little Horrid Henry in every kid, so to access the potentially naughty side of themselves through stories “is fascinating and freeing,” Hope says. “It’s an escape from everyday behavioral constraints, because characters actually do things that all kids think about but mostly don’t dare do.” Who wouldn’t want to fill a bath full of chocolate sauce and jump in, as Teddy and his pals do?

I'm Afraid Your Teddy is in Trouble Today by Jancee Dunn, $7, Amazon

Still, I used to worry that Teddy’s naughty behavior would give my daughter ideas, but it’s done the opposite. Because kids love to be righteous! They love to solemnly pronounce, “I would never do that.” Because kids can’t only learn how to be — they also need to learn how not to be. Young readers may laugh at these escapades, but they still know they’re wrong. Most of these books offer a sterling opportunity to talk about what’s appropriate and what’s not. As Hope says, “it’s a way to figure out what behaviors to avoid in order to be successful in the world.”

And with many of these stories, there are usually consequences, or at least some redeeming quality to the naughty characters that makes you understand them better. At the end of the Teddy book, the cheeky bear is so obviously chastened that a policewoman who is about to take him down at the station softens. She decides to let him go, and piles the animals in her squad car to take them home. I debated having the story end there, but couldn’t resist a final image on the last page, in which we see Teddy on the phone again, winking.

It’s a useful tool as they grow older, and are exposed to bad behavior that is darker and more complicated.

I’ve loved inhabiting Teddy’s world, where his wrongdoings are mild (the most egregious thing he does is urge a stuffed elephant to wear the kid’s mom’s underwear on his head). And as Dr. Hope said, it’s a safe way for children to form expectations of how to behave — a useful tool as they grow older, and are exposed to bad behavior that is darker and more complicated.

At the moment, my child is still naïve, but I know this golden period won’t last much longer. After I read the Teddy story to her for the 300th time, she closed the book and asked me what the worst thing a person could possibly do.

A horrible newsfeed of recent headlines scrolled through my mind before she offered a guess. “I know,” she said gravely. “Steal a bike. Right?”

Oh, kid, I thought, giving her a hug. If only that were true.