When I was almost 3 years old, my father died. He was 21. Growing up in the shadow of his death has been one of the most significant facts of my life — if I were a comic book superhero, this would be a crucial detail in my origin story. The logistics of what his absence has meant over time have changed, but the absence itself has never diminished. In a way, it has always been a presence, palpable and intrinsically understood. And now that I'm a mother, there are things I want the grandfather my children will never meet to know, or that I wish he could know. Whether he knows or doesn't know anything, at this point, is something I can't really comprehend or know how to consider (or don't want to, or consider in a way that doesn't generally sync up with how I think about most other things).

When I thought about writing this article, I didn't consciously realize that the 32nd anniversary of his death was only days away. I also didn't realize that I would be memorializing my most dearly departed on Dia de los Muertos. It's almost too appropriate. But, then again, it also seems perfectly fitting. My father's family has always been deeply concerned with legacy and memory: we have kept certain family names and stories for centuries now. Job Bowers, Revolutionary War soldier, murdered by Tories while on furlough for the birth of his son. William Bowers, one of two men in the state of Georgia to vote for Lincoln in 1860, almost lynched for his opposition to the Civil War.

Brian Bowers, my father. He only had 21 years to secure his legacy and I'm part of it. So, too, are his grandchildren, even though they'll never meet. Reflecting on my father through their existence, and as a parent myself now, makes me think about everything I wish he knew about what he left behind. Things like the following:

My Kids Are Amazing

I want everyone to know that my children are incredible, but I'd really like you to know that, because they're part you.

Whenever people talk about you, they talk about your sense of humor and profound, heartfelt kindness. My mother and your mother talk about your quiet sensitivity. I see it all in my two children. They're both funny, naturally and intentionally. They both display a level of empathy that takes my breath away. My son feels the world more keenly than most. My daughter will cry in sympathy with a lost baby bird in a cartoon.

Speaking of cartoons, they both share your love of Looney Tunes. I imagine you sitting on our living room couch watching "Baby Buggy Bunny" and telling them that you used to call me "Babyface Finster."

You don't look like a grandparent in these daydreams. In fact, you look like you in all the pictures I have of you: 21 years old or younger. So it's strange, imagining you as a grandfather when I can only conjure an image of you as a "kid" 13 years younger than me. You're like a granddad in the form of a cool uncle. Still, I imagine you reveling in the company of my children's with a grandfather's pride and warmth.

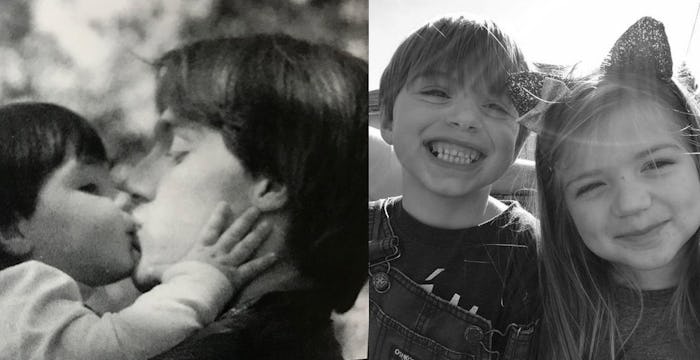

My Oldest Looks Just Like You

Not everyone sees it, but I do. The same cleft in the chin, the same long, Bowers face, the same fair skin and dusting of freckles across the nose. The same casually cool, somewhat detached, yet approachable vibe that, by all accounts, explained your ability to move seamlessly from clique to clique and my son's popularity among his friends.

It's heartening to see you in him, like you got to live on in some small way. You may not have had the chance to meet your grandchildren, but you still got to have a grandson with your freckles and hair and chin.

My Youngest Looks Like Me The Last Time You Saw Me

I yearn for any insight about you I can learn. You died before I was old enough to have the kind of conversation that would have enabled me to learn anything about your inner world. Having a daughter, and knowing what it's like to raise one, is something we have in common now. (We also both have sons — sons that look like you, incidentally — but you never got to meet yours.)

My daughter and I looked a lot a like as babies, and looking down at her when she was an infant, I can imagine what your view must have been and how that view made you feel. Our faces are less similar now, but our bodies, age for age, are almost identical: sturdy, thick-limbed, long-haired, tall and a bit graceless. I think of you watching me run around the way I watch her, and how, if you were here today, you might have a sense deja vu.

This point seems (and probably is) more about what I want you to know and more what I want to know about you. But I guess I want you to know that I feel like I can understand you a little bit more than I did when last shared the same air. We never reached that point in our relationship where I could try to understand you as an individual the way you understood me through that same lens.

You've Loomed Over Me My Whole Life

It's hard to describe what it's like to grow up very aware of death. Most people have a moment when death became real for them, like the passing of a grandparent or a pet. It's the sudden trauma of realizing that the concept you'd been vaguely aware of is, in fact, not hypothetical.

When death is a part of your pre-intellectual life, and one of your foundational experiences is being incapable of processing a trauma you feel acutely and the knowledge is not a sudden realization but an intimate understanding that only grows over time, you're a little bit different. Your life is a little bit different.

You're Hard To Explain To My Children

My son is only just starting to reach the age where he'll slough off his (developmentally appropriate) egocentricism. My daughter is nowhere near that point in her development. Any time my mother refers to me as her "little baby," my daughter either laughs or furrows her brow and declares "She's not your baby. She's mommy!"

They really don't have a concept of me as anyone's child, even though they know my mom and second father. So trying to explain how you come into play — when they can't easily fathom things they can't see — can get tricky. I tried the other day with my oldest by saying, "Did you know that I have two dads? One is Grandpa and the other is a man named Daddy Brian, who died a long time ago."

It went over OK, but I'm not certain it imparted the level of importance I'd wanted it to.

You Are Discussed & Remembered

It's critical to me that my children know you. So, we have pictures of Daddy Brian and tell Daddy Brian stories, and when we watch Looney Tunes we talk about how Bugs Bunny was your favorite.

Part of this is for the sake of your memory and for them to understand their place in a bigger world — to understand their own legacy. Part of it is entirely selfish. They will never understand who I am without understanding you.

Your Death Has Made Parenting Scarier

You died the father of a young child with another on the way. So, early on, parenthood and death were closely associated for me... that doesn't go away. Indeed, it hangs over you when you have kids.

Most children think of their parents as invincible. Even as adults we think of them as ever-present. I know, first-hand, that's not true.

I've Missed You Inexplicably

I don't know if I remember you. I have a few images of you that run through my head, but I also know those can be false memories, constructed via repeated stories, pictures, and home movies. They're real to me, undiminished over the years, but I still know they could just be my brain trying to make order of chaos, emotional and otherwise.

But even knowing this doesn't mean I don't miss you. It's not the same way you miss someone you haven't seen for a long time. Maybe it's more of a longing, a desperate reach for something you know belongs to you but that no one can give you. Something you should have, but can't. It's frustrating and hurtful and sad and, after a while, mostly leaves you numb until you really think about it.

I'm OK

See? I have two beautiful children and a whole lot of books and your mom's shiny hair! Obviously everything is great. I mean, just look at that thumb's up!

(But, really, it is. I thought you'd like to know that. I know how parents worry about their kids.)

Knowing You Loved Me Has Been Fundamental To Who I Am My Entire Life

You became godlike in your death: an unseen father figure whose love of me I'd been assured of through the stories and memories of others, but couldn't easily remember on my own.

I've never been inclined toward faith. Years of church and religious studies did nothing for my soul. I'm the kind of person who likes citations, sources, and receipts. Still, I've always had faith in your love.

Because of you, I understood death from an early age in a way that most children don't. But I've understand love differently, too, and from my earliest days. That force was just as invisible and just as powerful. I know it outlives us.

The cost of this knowledge was steep and terrible, but it has allowed me to love my children with a kind of confidence I don't think I would have otherwise. The confidence that, if I give them nothing else, I have given them this.