Homework sucks. I hated doing it and my kids aren’t thrilled about it either. I do still think it’s somewhat of a necessary evil: a good way to practice some of the day’s learnings. My only objection is the amount of homework kids get at some schools are giving. Luckily, my kids’ school assigns what I believe is an appropriate amount to my kindergartner (no more than 10 minutes) and my third grader (about 20 minutes, plus 30 minutes of reading, and yes, I count bedtime stories towards that). Still, kids will take every opportunity to complain about something, and homework is a ripe topic. So I have to be careful about what my participation level in their assignments.

I wasn’t raised in a family that paid to send me and my brother for extra test prep. My math tutor was my dad (by default, since he was home in the afternoons) and he had a penchant for numbers, but little patience with my reticence to share in that. I remember the homework battles vividly: me trying to explain this “new” math, and him arguing that his way was better (it was, but it was a harder sell to my overworked teacher). I swore I wouldn’t make homework a point of contention with my own children, and if it meant an occasional “bad” grade or a “re-teach” packet being sent home, so be it.

So here are the things I refuse to do when it comes to my kids’ homework.

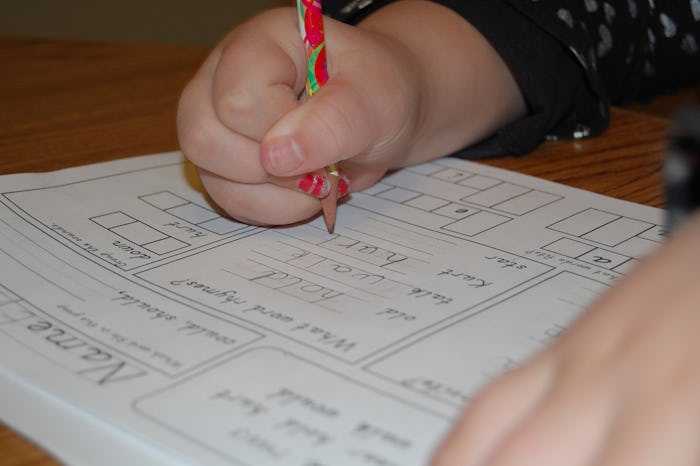

Correct Their Work

I may ask them to double-check it (“Can you look at this question again and see if you get a different answer?”), but I will not be erasing or filling anything in for them. We all want our kids to do well, but I'm not doing mine any favors by covering up their mistakes. How will the teacher accurately assess their grasp of the silent "e"?

Discount What Their Teacher Said

I’m a firm believer that the teacher is the boss of the classroom; He or she is the expert of that domain, not me. Did I learn math completely differently when I was a kid? Yes. But that doesn’t mean the “new” way is wrong. As long as my kid insists that “this is the way we learned it,” I will do my best to support the teacher’s efforts. And yes, that often means reading the textbook (instead of Netflixing) so I can better understand this totally weird-looking way my third grader is solving fraction problems.

Force Them To Study

I force a lot of stuff on my kids: baths, bedtime, room cleaning, washing hands after peeing. So by the time they were old enough to get homework (up to 10 minutes a night in kindergarten), they understood that some things are just their responsibility. The occasional meltdown occurs: Just the other night, my daughter stormed out when we were going to review a chapter for her math test the next day, because I had sharpened the “wrong” pencil. And you know what? I let it go. If she fails because she didn’t study, she needs to learn that lesson.

Reward Them For Doing It

It’s their job. It’s part of life, beyond which, it's a privilege; it's not actually part of so many kids' lives. My kids' biggest "problem" is that they get to go to school and fill their downtime with additional education? Right. Also, we’re lucky in that our kids don’t get an unreasonable amount of homework, so they still have time to play and chill and read books of their choice (OK, maybe that counts as homework). I don’t feel that homework is something so remarkable for them, as neuro-typical children, to have completed. If they meet an expectation a teacher sets, it's no big whoop. I save for the confetti for the truly amazing feats, like getting through dinner without dropping food on the floor.

Do It With Them

OK, this one comes with a disclaimer: I can’t do homework with them because I don’t get home from work until 7 p.m. They do their homework under the supervision of their babysitter. But unless they ask for help in understanding a part of their homework, I don’t see the point of sitting next to them while they work. I know I’d be tempted to direct them: “Put a space after that word before the next one.” “Hmmm, does the letter "b" face that way, or the other way?” Then they’ll just get used to me being there ready to chime in. School work is meant to condition them to think for themselves, drawing upon what they learned in class. If I’m there with the answers, where’s the incentive for them to engage their brains?

Type Up Their Work

Recently, my daughter had to type up a 200-word essay she had written in class. I helped her navigate the Word software commands, but I never touched the keyboard. Did it take her a full hour what would have taken me less than 10 minutes and did we both want to scream? Yes. But if I start doing any part of her homework for her, how can I set limits? “I’ve already been through third grade,” I tell her.

Project My Craft Dreams Onto Their Art Projects

My kids looooove using tape. There is no other way to adhere things, in their opinion, than with yards of Scotch tape, wrapped like ace bandages around cardboard cut-outs which I think are supposed to represent characters in Charlotte’s Web. Not sure. I gently suggest using glue, for a neater, more secure diorama — but this is their project. They’re the ones getting graded. For a Type-A person like me, this is a hard lesson. I just have to back away and nod enthusiastically when they ask if I like how it turned out.

Emphasize Grades

Understanding the material is more important than the grade. True, the grade usually represents how well the kid understands the lesson, but sometimes (a lot of the time, actually), they just made a careless mistake, or had the right answer but got points off for spelling. When my daughter gets bummed about a grade, I ask her if she is disappointed because she thought she could have done better. And that usually leads us to discovering that she either didn’t understand the material as well as she thought, prompting us to do more review until she does, or that next time, she needs to go back and check all her work again and correct any mistakes she might have made in her effort to get through the text quickly.

Compare Their Performance To Anyone Else’s

My third grader whines that she has more homework than her kindergartner brother. Or that I spend more time reading with him than I do with her. I try to explain that things are not equal — he is 5 and she is 8 — but they are fair. He gets the right amount of work for his age and knowledge, and so does she. I read with him because he is still learning how to; She reads chapter books silently to herself. So how do we level the playing field a bit? We let her stay up 15 minutes later than her brother now, not to have screen time, but to stretch out play time a bit to make things feel fair. I also put her to work making her own lunch for the next day. #winwin

Make Excuses For Any Subpar Effort

I don’t send notes in to their teachers explaining why their papers are crumpled or they didn’t finish their work (unless we truly had a catastrophic event happen). At their ages, they can be held responsible for taking care of their work and packing up their bags. I still help my kindergartner make sure he has everything he needs, and encourage him to write as neatly as possible, but for my third grader, I simply remind her to pack up her bag and that’s it. I noticed one morning she forgot the beloved book she’s engrossed in but I didn’t dash to bring it to her. She was annoyed enough at herself to remember it since.

Let Them Multi-Task While Doing It

It took me well into my adult life to realize multi-tasking is the surest way to sabotage quality work. Maybe there are some people out there who can do multiple things at once, but my mantra is “one thing at a time.” I chant it for my kids, who are so easily distracted by toys and screens and life in general. When we sit down to eat, we don’t play, or do math homework. We don’t have screens on while we try to work. My daughter isn’t practicing piano while my son tries to practice handwriting in the same room. I am a big believer of teaching my kids, who seem easily distracted, to focus on getting one thing done before moving on to the next. It’s my experience that doing two things at once takes twice as long and the results are half as good.

Chastise Them For Getting Things Wrong

Everyone makes mistakes. It’s hard for us as parents, sometimes, to see how easy it is to screw up elementary school homework. But for a 5-year-old, who couldn’t even write his own name a year ago, being wrong is just a step towards discovering how to be right.