Life

This Documentary Shows How The Paid Leave Crisis Is Quietly Crippling Families

When Ky Dickens became pregnant four years ago, she had been working at a small production company for about 12 years. She was the first women there to expect a child, so her bosses didn’t know how to handle maternity leave. They offered Dickens two paid weeks off, but the award-winning director “fought hard” for more time only to have her job threatened, she tells Romper. When Dickens went back to work, she felt like she was being punished for being gone. The experience disturbed Dickens so much that she decided to channel it into a new documentary exploring the cost of America’s paid leave crisis.

Zero Weeks, Dickens’ fourth feature-length film, is a stark and poignant look at the consequences of inaction on paid leave in the U.S. Dickens’ aptly-titled film follows six families as they struggle to make ends meet because of a lack of paid family leave in the United States. And in the end, it begs the question: Why do lawmakers fight against policies that would benefit workers and their families, and boost the country’s economy?

“This isn’t right in America,” says Dickens, who quit the production company to work on Zero Weeks as a freelance director. “This isn’t right, not for people, not for business.”

More than anything else, though, Zero Weeks wants you to feel outraged. Dickens interweaves powerful interviews, “tongue-in-check” animations, and illustrations to drive home exactly what America’s paid leave crisis is doing to working families. For some of the people featured in the film, that means taking an hours-long commute to and from work or undergoing cancer radiation therapy during lunch breaks.

How could this be? Let’s start with one fact: Among 41 developed countries, the United States is the only nation without paid parental leave — or paid leave of any kind, for that matter — according to the Pew Research Center. Compare that to Sweden, which offers new parents 480 days of paid leave at 80 percent of their normal salary. Or New Zealand, which offers mothers up to two months — the smallest amount of paid leave available among the 41 countries. (According to New Zealand law, the spouse of the employee who's given birth can receive up to two weeks unpaid leave.)

Democratic Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York filed legislation in 2013 to solve the United States’ leave problem, according to Fortune. The Family and Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) Act would provide up to 12 weeks of paid leave for childbirth, caregiving, or medical issues. But each time Gillibrand has introduced the FAMILY Act — 2013, 2015, and this year — it’s stalled in the legislature.

One common argument used against paid leave is that the United States already has a leave act. But it’s a disingenuous rebuttal, to say the least. Although the Family and Medical Leave Act does provide workers in the United States with some access to leave, it’s still a catch-22 for working families. On the one hand, the FMLA is important and necessary legislation: Under the 1993 federal law, employees receive up to 12 weeks of leave to care for a new child, help a sick loved one, or recover from a serious illness.

But those are 12 unpaid weeks, which means workers who need time off but cannot afford to lose pay are forced to choose between taking care of a sick baby or getting fired from their only means of income. A parent who takes leave without pay risks their financial stability, and can easily slip into poverty. That, in turns, creates stress and strains their and their family's mental and physical health.

“This is an issue of both economic security and family well-being,” Ellen Bravo, co-director of Family Values @ Work, a leading paid leave advocacy coalition, tells Romper. “People lose their jobs … and our economy suffers when that happens.”

Workers also have to meet strict requirements in order to benefit from the FMLA, which applies to businesses with 50 or more employees. That leaves out at least 40 percent of the workforce, says Bravo, whose work Dickens tracks closely in Zero Weeks. Conversely, as of 2016, only 14 percent of the U.S. workforce actually has access to paid leave through their employers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Compensation Survey.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen to us and the ones we love, and something is going to happen to each and every one of us. That’s why we should all care.”

When mainly Republican lawmakers fight against paid leave, they further marginalize workers who are already vulnerable to the country's poor labor and wage laws. In fact, a 2011 Human Rights Watch report detailed the depths to which a lack of paid leave hurts workers and their children. The main takeaway: Employees with little to no paid leave went into debt, were at risk of losing their jobs, and were more likely to delay infant and postnatal care.

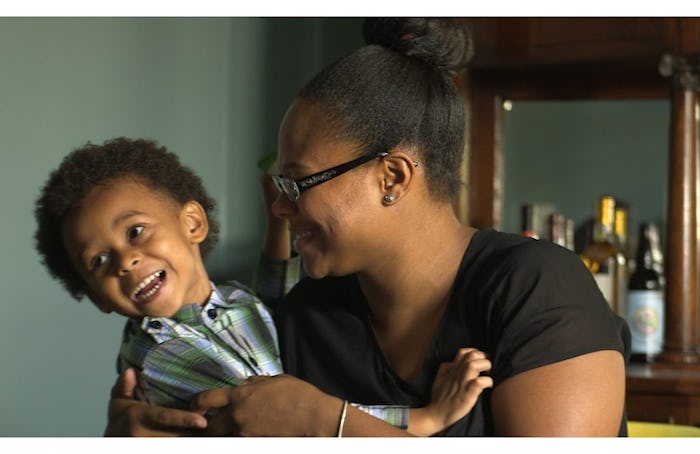

Take Jasmine’s story, for example. Jasmine, one of the mothers featured in Zero Weeks, was working at a daycare for five years when she had her child. Her job didn’t provide maternity leave, so she took extended time off without pay. The daycare also didn’t provide job security; when Jasmine was ready to return to work, her company already hired another worker. Desperate for work, Jasmine took a job that requires a two-hour commute on public transportation, to and from work.

“She was so happy to have another job within three weeks after having a baby,” Dickens tells Romper. “She was going to the job even though it was just so painful for her.”

She adds: “We shouldn’t be settling for such a crappy hand in life [while] other countries have figured out how to balance work and family.”

Without a federal paid leave policy, many working parents are also forced to make decisions they may not want to, such as going back to work sooner than intended. And studies do show that how soon you return from paid leave can impact your child's health. Working parents are more likely to breastfeed for longer if they're able to stay on leave for an extended period, according to a 2011 study published in Pediatrics. Although not every parent can or wants to nurse their child, studies do show that breastfeeding provides optimal nutrition for babies.

Another working paper, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) this year, concluded that paid leave policies offering up to 12 months off can improve a child's health, as well as benefit a women's career advancement. The report found that women are more likely to return to work if they have access to up to a year of leave, and they wouldn't see a negative impact in long-term employment or earnings.

“It affects your whole life, and the brain development and bonding time with your infant is so critical,” Bravo tells Romper. But a lack of federal paid leave means “being a good parent to your child or a good child to your parent is going to put them in financial crisis.”

“We can’t allow that to be the case,” she adds.

A large body of research has proven that paid leave benefits workers, their children, and the businesses they work for. Yet, mainly conservative lawmakers continue to rally against enacting a federal law that would mandate paid leave. Many of the anti-leave folk believe that offering their employees paid time off would hurt businesses and workers. But the facts don't support those claims.

Although there is a cost to providing a paid leave benefit, most businesses report seeing greater retention of employees and higher productivity, according to Fast Company. (That cost, by the way, comes out to less than $1 a week.) And a series of reports found that paid leave policies didn't hurt a company's bottom line; an overwhelming majority of employers in California — the first state to implement paid family leave — and New Jersey, for example, have reported a positive to no adverse effect on their businesses. Two other states, Rhode Island and New York, have also passed paid leave laws; New York’s goes into effect in January, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

And, as Dickens and Bravo mention, paid family leave affects everyone across every political ideology. To illustrate this point, both advocates point to Brian, another subject of Zero Weeks. Brian considers himself a conservative, they say, who used to be anti-paid leave. But then he found himself out of work, with a new baby, because of the United States’ pitiful family leave policies. He still holds conservative values, but he now fights for federal paid leave.

Ultimately, Zero Weeks wants to bring a sea change by changing people’s minds. Often, the paid leave debate is framed as something that only affects parents or people with chronic illnesses, and is divided along liberal-conservative lines. But, Dickens says, the need for paid leave doesn’t discriminate. And the simple solution — passing a federal paid leave law — will benefit everybody.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen to us and the ones we love, and something is going to happen to each and every one of us,” she tells Romper. “That’s why we should all care.”

Check out Romper's new video series, Romper's Doula Diaries:

Watch full episodes of Romper's Doula Diaries on Facebook Watch.