News

Clarence Thomas' Death Row Dissent Is Complex & Has Everyone Confused

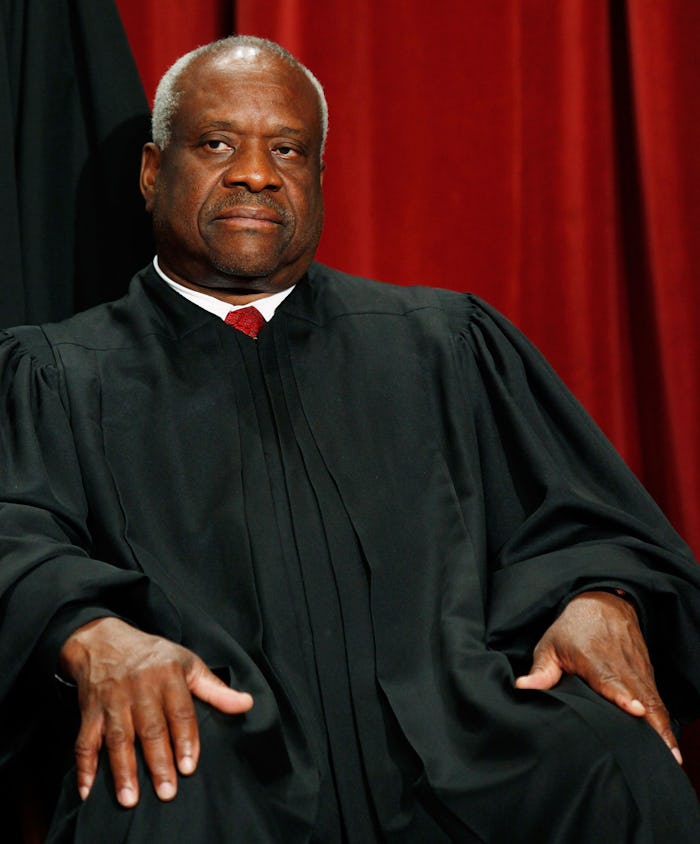

Three decades after Timothy Tyrone Foster was convicted and sentenced to death in the murder of an elderly white woman, the Supreme Court has thrown out the ruling on the basis that African American jurors were intentionally kept off the jury by the prosecution, according to The Washington Post. While seven of the justices sided with the majority opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas, the lone black justice on the Court, authored a dissenting opinion. Clarence Thomas' death row dissent is complex and sometimes contradictory, as might be expected in a 7-1 ruling.

At issue isn't Foster's innocence — he has previously confessed to the crime — but whether he received a fair trial under the auspices of an all-white jury and a biased prosecution. Foster, who grew up in the projects, broke into the home of 79-year-old Queen Madge White, broke her jaw, sexually assaulted her, and then strangled her before burglarizing the home, according to The Post. Over the years, Foster's attorneys have argued that Foster's status as a mentally disabled teen should have precluded a death penalty conviction.

Foster's case shifted focus to the issue of jury selection when Stephen Bright, Foster's attorney and an expert at death penalty cases, used Georgia's open records laws to procure the prosecution's notes from the original trial. What Bright found in the notes was shocking.

According to CBS News, the prosecution had highlighted each potential black juror with green highlighter, marked them with a "B," and added them to a list labeled "Definite Nos." With this evidence in hand, Bright argued before the Supreme Court that this was a clear instance of racial discrimination in jury selection, which was effectively banned via the precedent of Batson v. Kentucky, a 1986 Supreme Court decision establishing that striking jurors based on their race is unconstitutional.

According to Slate, Justice Elena Kagan said aloud during the proceedings, “Isn’t this as clear a Batson violation as a court is ever going to see?” Given the strength of the evidence, Justice Thomas' dissent needed to somehow make the evidence seem either illegitimate or irrelevant.

In his dissent, Justice Thomas brought forth two central complaints with his colleagues' decision. First was that the Supreme Court didn't have jurisdiction over the Foster case in the first place. The high court is supposed to intervene in state court decisions only when a federal law is in question; The Georgia Supreme Court, Thomas pointed out in his dissent, never mentioned a federal issue. "I therefore refuse to presume that the unexplained denial of relief by the Supreme Court of Georgia presents a federal question," he wrote.

What does he mean by "unexplained denial of relief?" Turns out that when the Georgia court refused to grant Foster the ability to appeal his case [aka, denial of relief] based on the racial exclusion argument, the judges said that his case had no "arguable merit." From there, they didn't elaborate. Thomas used the inadequacy and brevity of the Georgia Supreme Court's handling of the case to argue that no federal law was at stake.

Which is rather confusing. The total absence of an explanation doesn't mean that The Supreme Court lacks jurisdiction. According to the International Business Times, the other Supreme Court justices all felt that the Batson precedent, which is a federal precedent, was at stake in this case.

Clarence also argued that the evidence itself — the prosecution's notes — isn't compelling enough to reverse a lower court's decision. "The new evidence is no excuse for the Court's reversal of the state court's credibility determinations," he wrote. Clarence further tries to minimize the evidence, writing that "we do not know who wrote most of the notes that Foster now relies upon as proof of the prosecutors’ race-based motivations.” (According to the Associated Press, individual members of the prosecution have denied being the author of the notes.)

What's interesting, though, is that despite deeming the evidence insubstantial, Clarence seems rather threatened by it. "The Court today invites state prisoners to go searching for new 'evidence' by demanding the files of the prosecutors who long ago convicted them," he wrote in the dissent.

What Clarence really objects to, then, isn't the strength of the evidence, but that the court was allowed to see it. And unfortunately for Justice Clarence, who is a native of Georgia, placing "evidence" in quotation marks isn't enough to make it go away.