Life

How To Start Conversations With Your Kid About Race That Last Beyond Black History Month

February usually comes and goes with a few mentions of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks in schools, along with some modern-day Black leaders. But Black History Month is an opportunity to start an ongoing dialogue with kids about race and society that doesn’t end on the first of March. Research shows kids as young as 6 months notice racial differences, so why do we think school-aged children aren’t ready to talk about more?

I spoke with two race relations experts about how to make the most of this moment with your kids.

Talk about why we have Black History Month. The tradition came about because the American history being taught excludes the stories and contributions of Black Americans, despite the fact that enslaved Black people built America’s economy with hard labor. Unfortunately, that means parents don’t often know much Black history themselves — not outside of the standard civil rights facts and figures. It’s easy to assume that schools today are doing better, but that’s not the case.

“Part of the challenge here when we’re talking about Black History Month is lots of people don’t know Black history,” says Dr. Beverly Tatum, president emerita of Spelman College and author of “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?” and Other Conversations About Race.

“Students that take U.S. history in school rarely learn about the role of Black people in constructing historical buildings, fighting in wars, or inventions that propelled our country,” says Ebony White, assistant clinical professor of counseling and family therapy at Drexel University. “We rarely learn about the role of Black people in sustaining the economy and continuing to sustain the economy.”

Your kids will be interested to hear about the pioneering Black people who created some of the things we use every day.

Talk about racism. It’s unavoidable. School lessons about Martin Luther King Jr., Harriet Tubman, Thurgood Marshall, and other prominent Black figures are only as impactful as the context they are given. That means talking about race and racism at home.

“We have to talk about the language of racism,” says Tatum, “and how it has existed for a long time and has led people to treat black people like less than human beings and that was unfair.”

Fairness is a concept even preschoolers understand. And race, believe it or not, is something children notice as young as 6 months old. By preschool, kids are internalizing learned racial biases. Black History Month is the perfect opportunity to highlight Black leaders, activists, and changemakers while also framing why they are so remarkable in light of the racism that they faced and fought.

“One of the things embedded in these stories is some information about the struggle and what is the source of the struggle,” says Tatum. Yes, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat near the front of the bus, but why was she asked to? Kids need to be able to recognize racism to name it and avoid participating in it. Talking to kids about what they understand about racism and filling in the gaps is a good place to start the dialogue about race — and there will be plenty of opportunities to keep the dialogue going year-round.

Talk about people they share an interest with. A child who wants to be a writer can and should be introduced to amazing Black writers like Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and Nikki Giovanni. Tatum recommends parents use online resources, such as Teaching for Change to find age-appropriate books that match kids’ interests while also normalizing Black main characters and Black authors.

Kids of elementary school age who show an interest and curiosity in architecture can read Dream Builder: The Story of Architect Philip Freelon, the Black architect who designed the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “There are lots of kids that won’t imagine there are Black architects,” says Tatum. Introducing children to the idea of a Black architect seems simple, but it totally changes the messages kids receive in the media, and maybe even at home, about what it means to be Black.

Tatum also says some of the best conversation starters about Blackness and race are found in daily current events. Let kids ask questions and answer them as honestly as possible in a way they can understand. It’s OK for kids to ask about race. In fact, it’s ideal. “Some people go around the idea that you’re never supposed to mention race,” says Tatum. “But ... kids can’t name racism when they see it if they don’t know what it is."

Ask age-appropriate questions. In any and every conversation about Black history, parents have the chance to extend the conversation. White says the key to making sure kids see Black history as an important ongoing topic is for parents to first have an understanding of their experience.

“What does it mean to be Black?”

“Why do you think the history of Black people in America is important?

“What books do you read or shows do you watch that are about Black people?”

Such questions not only gauge kids’ understanding of Blackness and Black history, but they let kids know it’s OK to discuss race. Tatum recalls a story where her son came home from preschool and asked, “Is my skin brown because I drink chocolate milk?” He told her that his classmate said his skin must be brown because he drinks chocolate milk and his own skin white because he drinks white milk. She told her young son that his skin is brown because he has more of something called melanin in his skin.

“It’s possible to have age-appropriate conversations with children, but often white adults freeze up because they don’t know what to say — it creates a pattern of silence,” says Tatum. If kids know you’re listening and ready to answer, they’ll break the pattern of silence and keep the dialogue going whether it’s February or not.

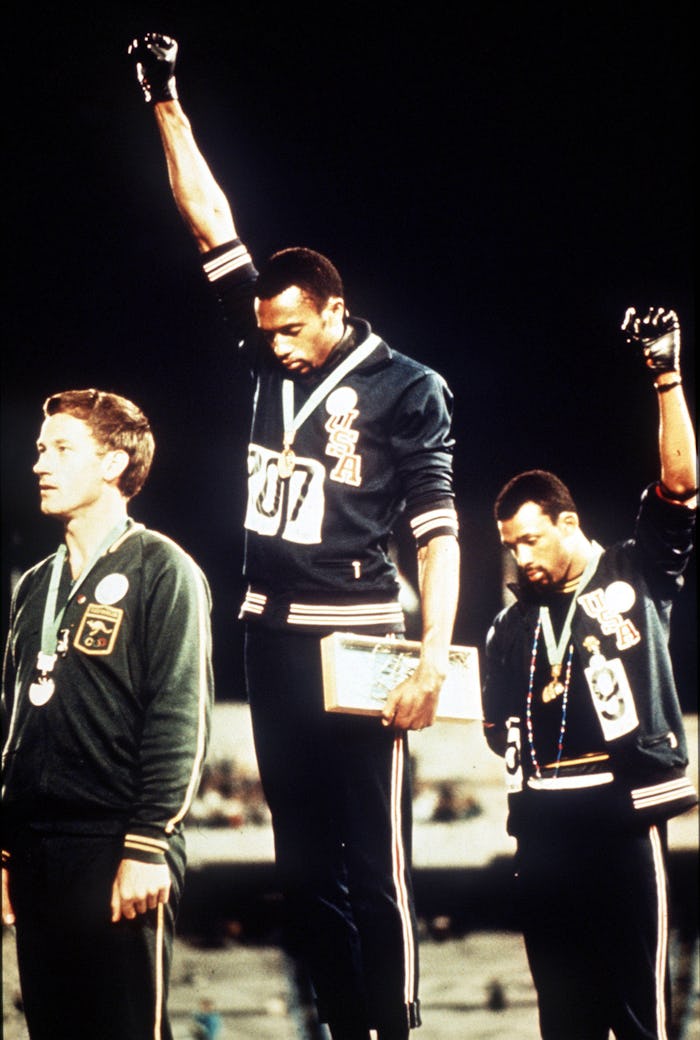

Top image caption: USA gold medallist Tommie Smith (C) and bronze medallist John Carlos give the black power salutes as an anti-racial protest as they stand on the podium with Australian silver medallist Peter Norman at the 1968 Olympics.