News

Does The Winner Of The Popular Vote Automatically Win The Election? Short Answer: Nope

If the Electoral College strikes you as complex, you're not alone. Aficionados of United States history will happily tell you about the conflict between states' rights and federal power, and how this conflict, which in many ways defines the nation, gave rise to an electoral system that results in bizarre things like superdelegates and town hall caucuses. On the eve of the 2016 presidential election, many Americans are asking a question, even though deep in their unhappy hearts, they already know the answer: Does the winner of the popular vote win the election?

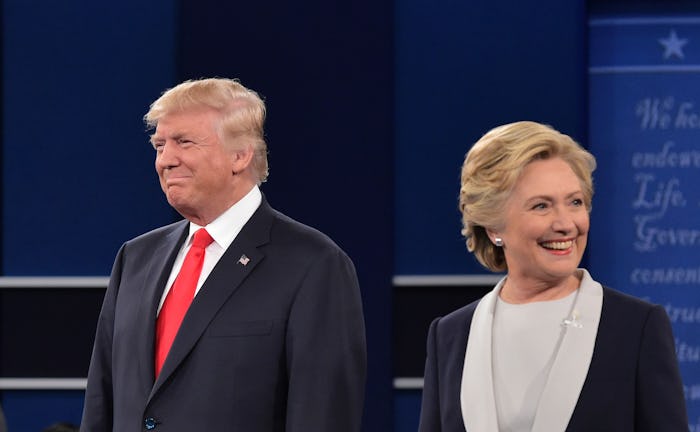

The answer, of course, is decidedly "no." The popular vote, which refers to the number of people across the United States who vote for each candidate, is essentially the gross total number arrived at by simple addition. X number of voters for Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton; Y number of voters for Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump. The popular vote is blind to state lines. It's the number arrived at when one person equals one vote. Which makes sense, no? If the election were determined by the popular vote, this would mean that if more United States citizens vote for Hillary Clinton, she would win. And if more United States citizens for Donald Trump, he would win.

But this is not how it works. This is not at all how it works. Rather, the national presidential election is determined by the Electoral College, which is comprised of individual people called electors. Each state has a given number of electoral college votes, which is based on the number of federal Senate seats that the state holds (two for all states) plus the number of House of Representative seats that the state holds. The latter is based, more or less, on the state's population size plus extraordinarily confusing stuff that relates to districting.

The populous state of California, for example, has 55 electoral college votes, while the states of Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming all have only three electoral college votes — hence rarely seeing these states as stops on the campaign trail. Typically, all of a state's electoral college votes go to whichever candidate won that state's popular vote. The exceptions are Maine and Nebraska, which sometimes split their electoral college votes based on state-specific rules.

Sounds simple, right?

In an article published by Vox this week entitled "Why the electoral college is the absolute worst, explained," contributor Andrew Prokop refers to the system as "ancient" and "magical." He further elaborates that it's a "patchwork Frankenstein’s monster of a system." Likewise, an NPR article published this week glumly refers to the "chorus of critics who have abhorred the Electoral College for generations."

In the end, the electoral college winner almost always corresponds to the winner of the popular vote. But in one recent instance that will haunt millions of Americans until their dying day, the electoral college split with the popular vote. That was the 2000 presidential election between former President George W. Bush and former Vice President Al Gore. In that infamous election, Gore won the popular vote by a margin of 540,000, but he lost the electoral college 271 to 266. Ultimately, the election came down to the state of Florida, where the vote count was so close that various recounts went on for five weeks before the United States Supreme Court ultimately handed the win to Bush.

If the election of 2000 wasn't enough to finally rid the country of the burden of the electoral college, it's difficult to imagine what will. Nevertheless, there are optimists and patriots who work toward establishing a national popular vote. This week, PBS reported on the efforts of Jeffrey Dinowitz, a Democratic state assemblyman in New York City who is championing The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, legislation what would compel participant states to pledge all of its electoral votes to the candidate who wins the national popular vote.

To date, 10 states have adopted the legislation, but it only goes into effect if the number of participant states' electoral college votes add up to 270, according to PBS. At present, there seems to be no incipient change to the Electoral College system. One person, one vote remains a dream for another day.