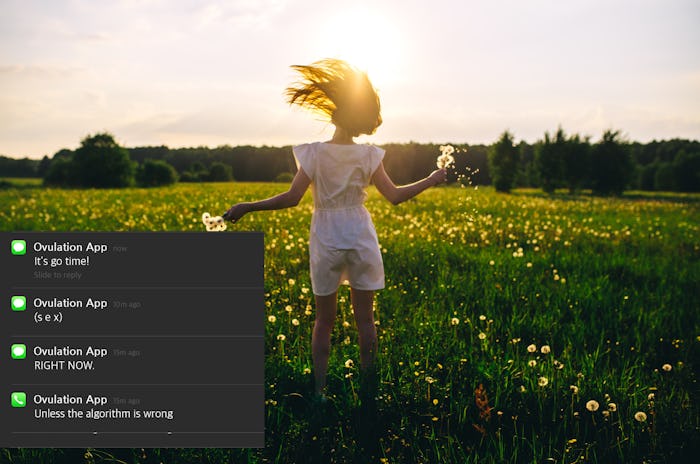

“The flowers are blooming!” said the pop-up alert on my phone. This was my period tracker app’s way of telling me that chances were “excellent for conception.” The app — the now-defunct Pink Pad — had a fuschia and red colorway that made every day feel like Valentine’s Day 1985, and was the primary tool I used to get pregnant with my first child (my husband was another tool I used). The word “vagina” did not appear in the strangely Victorian app; there were only petals (stamen?) waiting to be pollinated by sperm, and moons signaling the shedding of another cycle. When I added “flow” to my tracker, a fat red blood droplet would appear on the calendar for that day like crimson rain on a window. Tulips and daisies still proliferate in the fertility apps topping the App Store. Even among the offerings with a slightly more ~evolved~ user interface (read: less “barfy cute,” as one Redditor put it), the tone-deaf popups and alerts can frustrate users during the stressful phase of trying to conceive.

“You are on day 99 of your cycle,” read the fertility tracker Jessie Glocking, 30, was using to navigate family planning amid a diagnosis of PCOS that sees her period disappear for months on end. Glocking is blogging about her experience trying to conceive as a part of Romper’s Trying project. For her, it was the final insult. So why are so many of these apps so damn rude?

Tech has a well-known diversity problem. In 2011, women made up 20 percent of software engineers and programmers in the U.S., according to findings by the Level Playing Field Institute. When Apple launched its “Health” app in 2014, it allowed users to log their blood pressure, weight, sleep habits, food intake, and steps, but did not include the functionality for 50 percent of potential users to track their periods (Apple rectified this in a 2015 update to the app). At the time, TechCrunch noted that just 20 percent of Apple’s engineering staff were female. Female health is often forgotten or deemed a niche topic. It was wasn’t until 2017 that we women were gifted a breastfeeding emoji by the Unicode Consortium gods, following the addition of pregnant lady in 2016, creating a digital world in which women could suddenly do more than tango (💃) and have our heads massaged (💆).

There are now apps that can accurately predict your death, track comets, and record complex analytics about your ride at the same time as they divulge the location of American military facilities with precision, but accurately charting a woman’s period is often seemingly beyond the reach of the fertility apps on the market.

“I really wish there was a lesbian setting on this app because it's tiresome to be inundated with assumptions about the kind of sex I'm having. Not everyone who uses this app is having sex with male-bodied partners.”

Elizabeth Bradley of Milner, Georgia, says she tried two fertility apps simultaneously and found that, despite entering the same information into each, “the apps were a day apart on when I should be ovulating,” she tells Romper by direct message. Later diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), her periods, which varied in length, confused the apps.

“Months went on and my period came later and later each time... 32 days, 45 days, 60 days, and then the longest was 92 days between cycles. When that happens, the apps take the average length and just assume your time between cycles.”

On the other end of the spectrum, some apps don't let users input a cycle shorter than 28 days.

Diana,* a mother of two in Australia, also found her app was inaccurate when it came to predicting her fertility windows. "When it said I was fertile was completely different from when my mucus changed," she tells Romper by direct message. "In the end I ended up using fertility strips and mucus to track when I was fertile," a process that resulted in her now-9-month-old.

Bradley relied on fertility medication, ovulation kits, and basal body temperature readings to get pregnant, though she continued to input data into the apps. She is currently 35 weeks pregnant, due July 20, and says she feels lucky.

However, “the apps added to the stress of an already stressful situation, which was filled with what I felt (at the time) devastating news of having to begin a fertility treatment battle against PCOS.”

For many users, programs designed to encourage and prompt can quickly become wearing.

“Once my app alerted me and said ‘Did you have intercourse yesterday?’ during a time my husband was away on business,” recalls Alyssa Himmel, 29, who is also participating in Romper’s Trying project. "Rubbing it in my face."

There are scores of users who have had similar experiences. User Elizabeth Q, who reviewed her fertility app in Google Play, noted the insensitivity of app-generated feedback to user input about their biometrics and emotions. “The depression one is ‘cheer up, you'll get pregnant eventually,’” she wrote.

So if the lay person can hack fertility using paper and a pen, why do some of these apps do such a poor job for certain users?

Likewise, user Zoe T. found the one-size-fits-all advice of the app she downloaded did not serve her needs. “I really wish there was a lesbian setting on this app because it's tiresome to be inundated with assumptions about the kind of sex I'm having. Not everyone who uses this app is having sex with male-bodied partners.”

Morgan, 33, who now has a 9-month-old, tells Romper that after she downloaded a fertility app, she began to receive targeted marketing for fertility services in her inbox. “I don't like that all of a sudden I'm getting emails about freezing my eggs. Just kind of makes me feel old! I don't know how they decide who gets what emails based on demographics, but that was annoying to me.”

And just as users bring all manner of cycles, conditions, and identities to the apps, during the course of trying to conceive, they are often afflicted by other complications, which some apps handle better than others.

As an App Store reviewer noted of one popular fertility program, the programming does a poor job of accounting for miscarriage, which affects an estimated 10-25 percent of pregnant women, per the Mayo Clinic.

“There is no option to mark a miscarriage besides reporting the loss and resetting the app. Which is fine unless you plan to keep tracking […] This past time I didn't track my loss as a ‘period’ and now I'm on a crazy cycle day number,” read the review.

If you look at any TTC online forum, you learn that the women charting their basal body temperature, ovulation windows, HGH levels, LH levels, periods, secretions, moods, and sexual activity are extremely savvy about the science behind fertility. They speak in percentages, indicators, they chart. So if the lay person can hack fertility using paper and a pen, why do some of these apps do such a poor job for certain users?

If app developers want to create a product that is truly user friendly, they need to recognize that tracking a period means incorporating a person’s entire life, and not just their period.

“Fertility is not exclusively a women's issue, but most of the tracking technology and products in the space are focused on the female body, so they absolutely need to be designed around how women interact, track, and process information surrounding their fertility,” says Rachel Jones, a senior account manager at Fueled, a mobile app agency.

Simply involving women in the design and user testing stages can change the end product, she says, “but using female engineers or designers on a project of this nature is equally crucial.”

Jones recalls working on the MysteryVibe app, which paired with a smart vibrator and underwent substantial design changes after all-female focus groups provided input. “The original in-app messaging was much more heavy-handed,” she says.

Perhaps the most heavy-handed part of app design is the incentive to lure users into pay-for app subscriptions or “VIP” app features. Online app stores are littered with users fed up with ad pop-ups that block them from entering data.

Jam Kotenko, a pregnant mother of one who lives in the Phillippines, used free fertility apps to conceive both times.

"While all the apps I used were fairly useful upon signup, some of them asked you to pay a premium to gain access to more valuable insights like better articles, access to more comparative analysis of your daily logs (which is pretty much why someone like me would want to sign up for a fertility app in the first place), and better customization," she tells Romper by email. "I guess if I have legitimately been having a hard time conceiving, I wouldn't mind paying a bit for the premium membership, but for newbies looking for a simple way to maximize their ovulation period while also learning as much as they can about what goes on during conception, it's slightly annoying."

Still, in-app ads don’t stop all users. “This app used to be great but then it pesters you to pay to join. Which I said no to,” wrote Darius D. in a Google Play review. “We continued with the free version and now I am a dad.”

Touché.

Many of the fertility apps currently on the market allow users to re-skin the interface so it isn’t all pink or papered in flowers — though this sometimes requires a "pro" version of the app. But if app developers want to create a product that is truly user friendly, they need to recognize that tracking a period means incorporating a person’s entire life, and not just their period. Because fertility isn’t something that pops up once a month — it’s on user’s minds every day.

*Name has been changed at the person's request.