Life

The Invisible Maternal Health Crisis That The U.S.' First Indigenous Congresswoman Wants To Solve

In April, senator and 2020 presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren rolled out a plan for combating the nation's rising maternal mortality rate, especially among Black women.

Warren isn't the only Democrat running for president focusing on black maternal mortality. Senator Corey Booker introduced a bill aimed at preventing pregnancy-related deaths for Black women, and Senator Kamala Harris has introduced the Maternal Care Access and Reducing Emergencies (CARE) Act, a bill hoping to reduce the racial disparities in maternal mortality and morbidity.

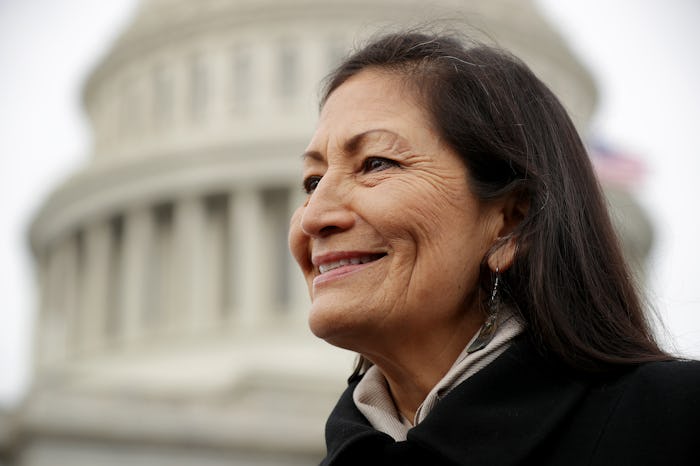

But there's a group of rural mothers being systemically left out of that discussion on maternal health. And Rep. Deb Haaland, one of the first Native American women to be elected in Congress, is no longer here for it.

"It’s been a long road for Native people, Native women, and so I feel like those of us who know what it’s like, we all need to stick together," Rep. Haaland said at the inaugural Mama's March policy roundtable on Tuesday, held in Washington D.C., and spearheaded by Mothering Justice, National Women's Law Center, and the Center for American Progress.

When we talk about the mortality rate for African American women and mothers, we should also be talking about the rate for Native American women.

The goal of the event was to center and discuss issues that impact mothers of color, including maternal justice, affordable child care, and earned paid sick time and paid leave.

"We need to make sure that we are echoing our voices and finding ways to make sure people know and understand," Rep. Haaland told the room. "When we talk about the mortality rate for African American women and mothers, we should also be talking about the rate for Native American women."

Native American and Alaskan Native women are 2.5 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white women, according to a newly-issued report form the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But rarely are indigenous women discussed when political pundits, presidential hopefuls, and even activists are navigating the most progressive of spaces.

This glaring oversight won't cloud Rep. Haaland's vision, or keep her from representing her community and her people as she walks the halls of Congress. As a single mother and descendent of the Indigenous peoples who migrated to the Pueblo of Laguna in the late 1200s, Haaland sees herself as more than just a newly elected Congresswoman and one of the historic "firsts" this country celebrated after the 2018 midterms.

"When I go home to Laguna, yes, I have to wash dishes. I have to cook for my mom. I have to do all of those things, because I’m not just a member of Congress. I’m also a daughter. I'm also a mother. So when my daughter gets sick, I still have an obligation to take care of her, to make her soup, to do whatever it is," Haaland said. "You don’t stop being yourself just because you get elected to something, you still have obligations as an individual and that really keeps my vision clear."

That vision includes protecting the Affordable Care Act, a landmark piece of legislation that, Haaland says, made it easier for Indigenous people to access health care.

My aunt, when she had her first child at the Indian Health Service in Winslow, Arizona... it was a terrible, terrible, horrifying experience. I don't want that to happen to anyone else.

"The Affordable Care Act was something that really helped Indian country a tremendous amount," Haaland tells Romper. "Mainly because of Medicaid expansion. It allowed Indian Health Service to third-party-bill for services, which made them able to, you know, be able to offer more services to Native communities. I don’t want to see the Affordable Care Act go anywhere. In fact, we need to expand it and make it more available to more people."

The limited access to health care for rural Native American women is personal for Haaland, and the impact of that limited access hits very close to home.

"Just within my family, there have been so many experiences of people not getting the health care they need," Haaland tells Romper. "My aunt, when she had her first child at the Indian Health Service in Winslow, Arizona... it was a terrible, terrible, horrifying experience. I don't want that to happen to anyone else, so I need to keep making sure that I’m listening to those stories, that I’m moving them forward so we don’t go back where we were before."

For Haaland, that means ignoring whatever the Republican-majority Senate does. Mitch McConnell, the Senate Majority Leader, has blocked votes on everything from election reform to spending bills, so it's unclear whether or not legislations aimed at combating the nation's maternal mortality rate would pass the Senate.

"We can’t think, 'Oh, what if the senate doesn’t pass it?' We just have to forge ahead with the legislation that we know is going to help American families," Haaland says. "We need to keep our country in mind and worry more about them and less about Mitch McConnell."

Rep. Haaland understands that the cards are stacked against her in a game presided over by people who have a fundamental misunderstanding of Native American people, their culture, and their unique needs. But she is helping to change this, bit by bit. Simply by being an elected representative of the United States of America, her seat at the table gives credence to the voices of Indigenous peoples across the country.

"A lot of folks think that fry bread is our Native America traditional food," Haaland said. "In reality, it's not. When the government moved Native Americans off their tribal lands and marched them to Oklahoma, Mosque Redondo or wherever, the commodities they got, the government surplus, was flour and lard. They had to learn to cook with the things they were given."

For Rep. Haaland, she is ready to work for Native American moms with what she has been given: a seat at the table, and a view to where we need to be.