Life

What Baby Geese Can Teach Us About Bonding

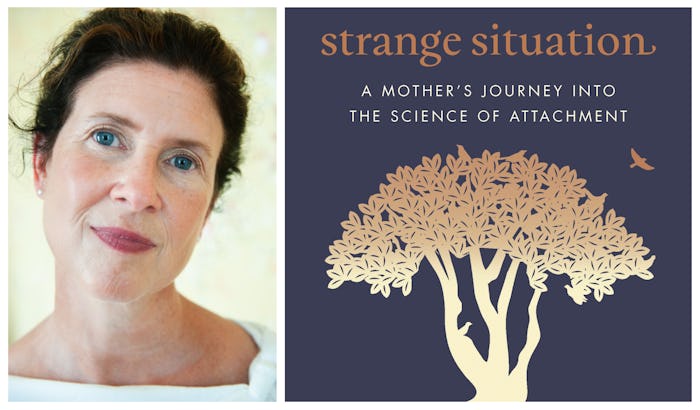

In the first year of life, babies ideally form a secure attachment with their parents, but how does that process work and what does it look like? Researcher and writer Bethany Saltman began a deep exploration of the science behind that bond after her daughter Azalea was born. In an excerpt from her book Strange Situation: A Mother's Journey into the Science of Attachment, she looks at how imprinting begins even before birth in goslings, and finds similar patterns at work between human mothers and babies.

When the future Nobel Prize–winning scientist Konrad Lorenz was a young boy in Austria, his neighbor gave him a day-old duck. He was delighted to see that the duck seemed to treat him more like a parent than a member of a different species. As a boy, Lorenz didn’t just love animals; he wanted to be one, and a greylag goose specifically.

Years later, in 1935, when Lorenz was a thirty-two-year-old physician, still obsessed with animals in general and birds in particular, he published his most famous paper: “Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels” (The Companion in the Bird’s World). He had observed almost thirty species of birds living in and around his parents’ Austrian estate and had cataloged their behaviors. Eventually he began raising some of their chicks. In the paper, he describes the experiment wherein he divided a clutch of goose eggs (seven to ten) into two batches — one to be raised by its mother in the usual fashion, the other to be raised by him as he mimicked the clucks and coos of the mother goose. He would call to his small flock with a nasal and slightly syncopated “CAW-caw-caw. CAW-caw-caw-caw-caw.” They would run, and later fly, to his feet.

When goose chicks are born, they turn to the first moving creature they see for protection and care. This evolves into the chicks identifying that creature — whether goose or human — as their mother. They learn to track their mother by the sound of her voice. Which is how he discovered that the little goslings followed whomever they saw first—a genetic propensity that farmers had long noted but Lorenz actually named. He called it “imprinting.” And he found that there was a period of twelve to seventeen hours after birth in which the gosling and many other birds would attach to whatever creature they saw first. It was love at first sight. And after about thirty-two hours, it was an endless love: regardless of who fed the little chicks, they would return to their original “mother.” Food could be used to reward the birds and enhance the imprinting that had already occurred, but it was not the main motivator.

She gently plucks an egg from a tan ceramic incubator and holds it to her ear. 'Vee-vee-vee-vee,' she calls, her voice lilting up at the end as though asking the egg a question. The gosling answers from inside the egg with a high-pitched series of chirps.

For thirty years Lorenz lived among the geese during what he called his “goose summers,” imprinting goslings on himself, young graduate students, even objects: white balls, rubber boots of different designs—striped, zigzag, and polka-dotted. The little chicks followed whoever or whatever was first put in front of them.

In 1975, the National Geographic Society sent a film crew to the Max Planck Institute, where Lorenz was the director. The film (starring a young Leslie Nielsen as the narrator!) shows Lorenz’s team of young German graduate students raising their own clutches of goslings. A young woman named Kristine demonstrates how the process starts before the chicks hatch. She gently plucks an egg from a tan ceramic incubator and holds it to her ear. “Vee-vee-vee-vee,” she calls, her voice lilting up at the end as though asking the egg a question. The gosling answers from inside the egg with a high-pitched series of chirps.

By the middle of that summer, the gosling and his mates were plump adolescents with fawn-colored pinfeathers. They joined the other clutches of goslings in a grassy field. They found Kristine by her yellow-and-black-striped rubber boots; other goslings followed graduate students who wore polka-dotted boots or ones with zigzag designs.

Like one morning in Manhattan, when I was trailing behind a woman walking her three kids to school. Before crossing the street, the mom and the youngest girl turned left, but the other two—another girl and an older boy, morning-weary, headphones on—didn’t notice and were about to walk into the cross-walk until they realized that their mother had changed course.

And then they, too, wordlessly turned the corner. It was like magic, that invisible something that kept those sleepy, tuned-out kids in tow, trailing after their mother, staying close.

Imprinting changed everything for Bowlby. The idea of an instinctive need to connect, attach, imprint a baby upon its caregiver helped him build a case for why those early relationships were not just some soft-focus happy place motivated by hunger, but a core aspect of the mechanics of our bodies and minds — an imperative, as critical to our way of being as following is to geese. Which would help explain why the consequences of early separation and deprivation could be so dire — it was the thwarting of a basic need.

One particular piece of Lorenz’s work became especially important to Bowlby’s idea of attachment, and that was the concept of “social releasers,” the term Lorenz came up with to describe the instinctive back-and-forth he noticed between animals of the same species, but also between himself and his geese.

This idea underlies the very concept of attachment — that innate call-and-response between babies and their caregivers, which leads to what he referred to then as mental health, or what he and Mary would soon call a “secure attachment.” The idea of social releasers is simple: the reaction in one body is triggered into being through the action of another, but it’s one of those things that is so much a part of our everyday experience, it can be hard to notice. A social releaser is different from a reflex, which lies dormant until a stimulus arrives. In other words, it’s our reflex to giggle or recoil when tickled, but there the reaction ends — in the person who’s been tickled, as opposed to then triggering a chain reaction of tickling. And a social releaser is different from a physical need such as hunger, which exists autonomously within each of our bodies. Even if we were alone, we’d eat.

A social releaser releases something social, something that moves back and forth between socially engaged creatures. An easy-to-understand social releaser is the birdsong, which invites other birds to respond; we all know what that sounds like. But there is an infinite amount of social releasing happening every minute of every day in creatures great and small, including fish, reptiles, and insects, through cueing mechanisms like pheromones, feathers, dances, looks, physical touch, sounds, and smells. Even trees relate to each other, sending signals back and forth through their interdependent networks of roots. When someone smiles at us and we smile back, we’re simply unlocking an expression that, viewed through a social-releasing perspective, belongs just as much to the person who released it in us as it does to us. Even our smiles don’t ultimately belong to us. We think we are solo actors, just going about our business, but we’re missing how totally connected we are.

Like when Azalea cried and my breasts tingled as they filled with milk.

This is an except from Strange Situation: A Mother's Journey Into The Science Of Attachment, out April 21 from Ballantine Books.

From the book STRANGE SITUATION by Bethany Saltman. Copyright © 2020 by Bethany Saltman. Published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.