Life

Author Jerry Craft On Seeking Diversity For Our Kids... But Not Ourselves

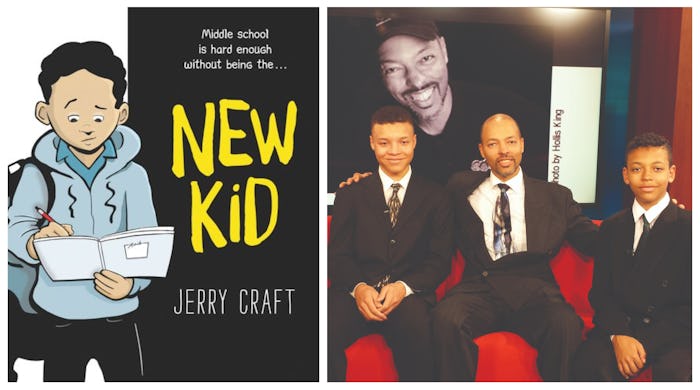

We have all felt on the outer at some point, but what if there is a racial component to that feeling? Jerry Craft's New Kid (Harper Collins, February 2019) explores that space, based on the Harlem-born artist's own teen years as a Black student at an elite — and mostly white — private school. Interspersed in with Craft's own struggles are the experiences of his two adult sons, who went to an equally prestigious and culturally homogenous private school in Connecticut — the after-effects of that isolation can last decades, Crafts tells Romper.

In New Kid, seventh-grader Jordan Banks is from Washington Heights, in upper Manhattan, and he has just started attending a wealthy private school in Riverdale chosen for him by his parents. He struggles daily to straddle the huge cultural divide between his predominantly white and wealthy school and the life he has at home. Banks doesn't want his buddies from his own neighborhood to see him getting into a friend’s fancy car or reading a book, nor does he want his new friends from school to view him as from “the wrong side of the tracks.”

Jordan faces this balancing act constantly in the book, because Craft himself lived it: he had his home life and school life, and his two universes rarely collided. He learned to code switch, a concept explained by NPR, between two worlds as a survival skill. “At my high school reunion, the few students of color who were now in their 40’s and 50’s were breaking down crying from the alienation that they experienced,” Craft explains to Romper.

Why, then, did Craft and his wife choose a similar school for their two boys? They weighed their options carefully and decided that the benefits of the smaller class sizes and individual attention outweighed the downfalls. Craft also knew that by being more intentional in his parenting, he could help his boys navigate some of the pitfalls and struggles of being a racial minority in their school. “I think that as the parents of Black children you definitely have to do more preparation," he says. "I think I prepared my kids much better than my parents did for me. My parents, I think, just felt so fortunate that I got into this prestigious private school that they assumed I was all set, as opposed to them realizing there might be issues me with fitting in.”

When my son was in first grade, there were two Charlies. And [the kids] would say ‘Black Charlie’ and ‘white Charlie.’ Like already, there goes the innocence.

So when he became a parent himself, Craft and his wife prepared their sons for what they would experience at school, telling them, “When they mention Black History Month, be ready for every eye to turn to you. They will think that you are the sole representation of Black culture."

And unfortunately, the preparation proved necessary very quickly. "When my son was in first grade, there were two Charlies. And [the kids] would say ‘Black Charlie’ and ‘white Charlie.’ Like already, there goes the innocence."

Despite the young age at which his sons started to experience being perceived as different, Craft believes that his sons were more accepted than he was by their peers since they started at their school at the pre-k level.

The Craft family also lived and owned a home in the school's community, so his sons weren't straddling two worlds quite as much as their dad had once been. In fact, the boys were popular, well-liked, and they didn’t get told they "acted white" like Craft did as a kid. They were invited to birthday parties, sleepovers, and weekends in the Hamptons regularly. But Craft couldn’t help but wonder if everyone wanted a token Black friend for their kids, a modicum of diversity on an acceptable level: “My sons were passed around like currency... I would drop them off at one house, assuming it was for the weekend, and get called to pick them up somewhere different.”

But for Craft and his wife, the picture was very different. They made an effort to be part of the boys’ daily life and the school culture, with Craft's wife getting involved in the PTA. Craft himself strove to be a positive Black male role model in the school, coming to campus to do cartooning, to make ice cream with students, or to bring in magazines and talk about his job. “I didn’t want their only interaction with a Black man to always be the kitchen staff, or going down to the homeless shelter for a day of public service. I didn’t want their only impression of a Black man to always be sticking a sandwich in their hand."

Despite their efforts to be involved with the school community, the couple would inevitably hear about dinner parties that they had not been invited to at the pickup line after school, witnessing a social scene of which they were on the fringes. “The same diversity they wanted for their kids, they didn’t seek for themselves," Craft says of the parents at his sons' school. "They want to teach their kids about diversity, but they are not walking the walk. They want them to have Black friends, but the only people of color they surround themselves with is a maid.” It was a world away from how he grew up — commuting from “the wrong side of the tracks” to actually living and owning a home in the desirable neighborhood — and Craft still often felt like an outsider.

The teachers seem to think [black kids] need more discipline and not the same loving approach other kids get.

But as his new book hits shelves and pre-sale copies get passed around, Craft has been encouraged by how Jordan Banks’s story — which is really the story of him and his sons — is affecting people. “There is definitely a lot of emotion from Black adults who went to private school, saying ‘Oh my God I wish I had this book when I was coming up!”

Craft has also been pleased with how profoundly the story has affected white teachers reading it. They get so angry at the white teacher in the book, saying, “She is such a good character, but I hate her…,” which is exactly what he wants. The story is making adults react in a big way, forcing them to realize that they have done many of the things the white adults in the book erroneously do. He believes Black kids need to be prepared for the way the world treats them, their parents need to prepare them, and that teachers and educators need to realize how much power they wield over these kids. “Specifically black boys,” Craft continues. “The teachers seem to think they need more discipline and not the same loving approach other kids get.”

The personal reflections of his own experiences highlighted by Craft's artistic skills create a book that is an important read for people of all ages and backgrounds. “I think of my book a little like Shrek. There’s stuff that will make the little kids laugh, and profound stuff that will go over their heads and the teens and adults will totally understand.”

New Kid is now available from Harper Collins.