Life

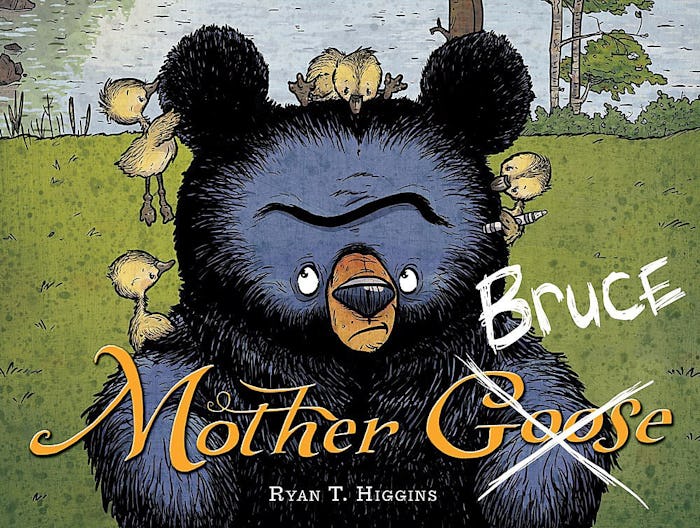

Why We Have To Believe In Winnie-the-Pooh, According To The Author Of 'Mother Bruce'

Reading a book 200 times is a surefire way to find out whether you love it or want to throw its rhyming llama couplets into the diaper pail. Children's books especially do a tricky dance for an audience of squinty-eyed parents and wide-eyed tots: the best ones, like a syringe of infant-suspension Tylenol, have a little something for the parent at the end. These are the ones we are celebrating in This Book Belongs To — the books that send us back to the days of our own footed pajamas, and make us feel only half-exhausted when our tiny overlords ask to read them one more time.

I thoroughly believe that books read during childhood can shape the direction of your life. Special books spark special interests, grow imaginations, and — if you are lucky — deliver a faithful friend or two to your side.

I grew up in a house on the edge of the woods. There was a little path that went from my backyard, through the old stone wall, between a stand of hemlocks and into the forest. I spent most of my childhood in those woods. I climbed trees, made forts, and made up stories about the animals that lived there. And I imagined that, if I looked hard enough, I could find Eeyore's run down house of sticks or Winnie-the-Pooh's front door (under the name of Sanders) nestled at the base of an old elm tree. And maybe, MAYBE, if I waited long enough by the little stream, I might see Calvin and Hobbes walking across a fallen log bridge on their way off to an adventure. This is the woods that my imagination grew in.

I don't remember exactly when my mom read Winnie-the-Pooh to me for the first time, but I must have been younger than 4 because I recall telling a friend in nursery school that I lived next to the Hundred Acre Wood. I was also a very big fan of the movie and the TV show. Reading about Christopher Robin and his ambiguously real animal friends, and watching stories about them play out on the screen became a big part of my childhood. And they mean a lot to me as an adult. I still laugh over Pooh walking around in circles, tracking possibly "hostile" animals and I get the warm fuzzies reading to my children about Piglet and Pooh giving Eeyore his birthday presents.

The stories teach us to slow down, think for ourselves, be kind, and not to pester bees while floating from a little balloon.

We all see bits of ourselves in one or more of the characters from The Hundred Acre Wood. The stories teach us to slow down, think for ourselves, be kind, and not to pester bees while floating from a little balloon. They may be animals and they may be imaginary, but their innocence and zest for adventure makes Winnie-the-Pooh and the gang better company than most people.

I also remember the first time I read Calvin and Hobbes. I was in first grade. I couldn't understand half of the words Calvin said, but I was hooked. The art and humor were easily accessible and held my 7-year-old attention for hours on end. As I got older, the imagination and philosophical underpinnings kept my interest, as the comic strip seemed to grow with me. Calvin often acts like a little brat, but there are times when he asks big questions and times when he and Hobbes show the true importance of doing nothing on a summer day.

I became obsessed. I did school book reports on Scientific Progress Goes Boink and on Yokon Ho! I wrote at least a dozen letters to Bill Watterson. I even got a stuffed tiger and named it Hobbes (my kids have him now). I am still obsessed. I have this dream where I walk into a dusty old bookstore at closing time and find a shelf filled with rare Calvin and Hobbes books that I don't have. Obviously, I want to buy every one of them . . . but, in my dream, I have lost my wallet and have to rush out of the store asking the owner to keep the store open for me while I run home for money. I wake up in a panic.

Even though Christopher Robin and Calvin aren't that similar in mannerisms, their imaginations have a lot in common. They both have best friends that are sort of real, but sort of imaginary. It's up to the reader to decide which reality to believe. I had an active imagination like both of them, but I was different from them in one respect. I never had any imaginary friends — or none that I would pretend were real. I did have an ever-evolving cast of imaginary characters that I would invent stories about. And, even though I never asked my mom or dad to make extra tuna sandwiches for these characters, they were real in that they were a part of me. I wouldn’t have pretend conversations with them, but I would imagine them having conversations with each other, and having adventures in my forest. And so, over time, the woods behind my house became a playground for my imagination and a neighborhood for the critters I thought up.

I never really wanted to be Calvin or Christopher Robin. I wanted to be A. A. Milne and Bill Watterson. From a very early age, I didn't want to create imaginary friends for me to play with. I wanted to create stories about my imaginary friends and share them. Calvin and Hobbes and Winnie-the-Pooh were critical in my development as a storyteller.

Winnie-the-Pooh is real. Hobbes is real. All the characters in those stories are real.

These books and characters from my youth have remained close friends throughout the years, and I have a sneaky feeling they will always be with me. As I watch my children learn to choose books for themselves more and more, I am always hopeful that they will find a forever friend that will spark their imagination indefinitely, as Winnie-the-Pooh and Calvin and Hobbes did for me nearly 30 years ago.

The books I make are sort of like little windows into my head. A good deal of my imagination has been fed by the imaginations of Bill Watterson and A. A. Milne. Part of what made their stories so great is the depth of the characters. Winnie-the-Pooh is real. Hobbes is real. All the characters in those stories are real. Their adventures aren’t just stories that the characters have been dropped into for the readers’ amusement. The stories are driven by the individual personalities of the characters and the interplay between them.

I try to do the same thing in my Mother Bruce books. Bruce the bear, and his unintentionally adopted family of geese and mice have very distinct personalities. It’s a lot easier for me to just let Bruce and the gang be themselves — and not force them to fit into a particular storyline. I want my books to be snapshots into the lives of my imaginary friends. They inhabit my imagination at all times and they are going about their business even when I’m not checking in on them. Hopefully I check in when they’re doing something amusing. And hopefully I’m able to translate their shenanigans in a way that readers will enjoy.

Ryan T. Higgins's latest book, We Don't Eat Our Classmates, is out June 19 from Disney-Hyperion.