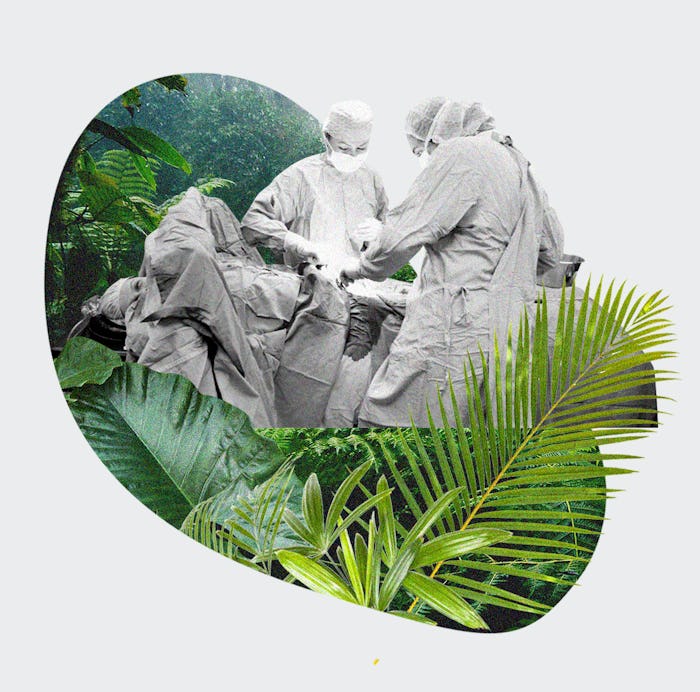

When you read a lot of birth stories on the internet (guilty), you become familiar with two distinct narrative tracks. Bad birth stories, sometimes followed by years of regret, are often marked by a sense of personal failure and a “medicalized” experience at the hands of a bad actor. “I gave in to my fears,” Rana Gosani, a mother of three in Cork, Ireland, says of her first birth. “I don't even remember what the doctor looks like: he breaks my water, cuts my vagina, and I don't see him again.” When things go well, it is usually ascribed to the courage of the birthing person, and absence of medical intervention. We see these possibilities juxtaposed in birth stories on Reddit and Twitter; in the woman who free-birthed under a jungle palm in Costa Rica, where a Pitocin drip cannot reach, and in the stereotype of the impersonal obstetrician for whom baby bumps resemble casseroles on a buffet line waiting to be sliced into.

An obstetrician in The Business Of Being Born, Dr. Michael Brodman, writes off unmedicated births as “feminist machoism.” Birth is merely a sector of the market economy, warns a paper in the CUNY Law Review. The result has been a population of people terrified of the care they might receive in hospitals. “I do think that many home births result from women's distrust of organized obstetrics,” says Dr. Mary Jane Minkin, M.D., clinical professor of obstetrics at Yale School of Medicine, by email.

“I lost control over my birth,” says Gosani, who planned to deliver in Ireland’s private system after two public hospital births so she could have the birth she wanted.

Then came the pandemic.

In March, seven pregnant women admitted to Columbia University Medical Center to give birth subsequently tested positive for COVID-19. Two had been asymptomatic and exposed dozens of staff to the virus. The episodes indicated “a need for immediate changes in obstetric clinical practice,” concluded one study, following which two major New York hospital networks banned all birthing support people from delivery rooms. The policies were quickly criticized as infringing upon the rights of birthing people and potentially increasing maternal and infant mortality, as a Change.org petition warned, though the rules also offered protection from the threat posed by COVID-19 to infants and mothers. There was a run on midwives by women who wanted to opt for home births instead. Hospital conditions were suddenly being compared to The Handmaid’s Tale, but it was hard to say who the bad actors were, as physicians in their third trimester braved emergency rooms, and nurses left their children to log long hours in overtaxed ICUs.

Chelsea Martin is expecting her first child, due May 1, in Staffordshire, UK. "I was told I was not going to be able to set out a birthing plan," Martin says, "and that anything that I want I would only get on the off chance that it will be available on that day."

Danielle Berkes, of Pennsylvania, began her induction on March 11 and delivered her second child on March 12. Her husband was present at the birth. During the night, a change came through.

At 7 a.m. on the morning of March 13, Berkes was informed that the hospital’s visiting policy permitted just one support person and no children in the recovery ward. “It was weird being in the hospital with just my daughter," she says.

Rebecca* had a scheduled C-section on March 27, when the full birth partner ban was in effect in some New York City hospitals. Rebecca, who preferred not to use her real name due to the nature of her job, entered the lobby of the hospital, where they were welcomed by a large sign that said “No visitors allowed.” She said goodbye to her husband, and was wheeled away in a mask to be tested for COVID-19, then delivered to the operation room.

“Literally as they were about to make the incision,” a pediatrician informed her that the hospital policy required the baby to be separated from her after birth until her test results came back, Rebecca recalls. “I'm like crying, I'm like I can't hold my baby, I can't have like skin to skin, you know I'm already doing a C-section, I want to breastfeed, all of these things in my birth plan kind of went out the window.”

Before this strange moment in obstetrics, birth plans were supposed to act as a mediator between an OB and their patients. You can still download a PDF titled “My Preferences for Labor and Birth” from the website of the New York hospital where I delivered my first child — a three-page menu of options; just check the box to order intermittent monitoring. VBACs are sometimes not on the menu, and care providers are careful to talk about “preferences” rather than “plans” because birth is unpredictable — somewhere between 10 and 15% of deliveries will require intervention, per the World Health Organization — and not all preferences are reasonable (these have been well satirized) or possible. “[Birth] doesn't have to be full of machines, IVs, of doctors passing out drugs like it's happy hour, and it certainly doesn't have to be in a hospital," wrote Alicia Silverstone, who had an emergency C-section, in her 2014 book Kind Mama.

Of course we need to keep ourselves and our patients safe when it comes to infection. I think we still have to have a sense of humanity about all of this.

Hospitals, which see 98% of births in the U.S., have taken many home-birth and birthing-center practices on board, as the efficacy of doulas, immediate skin-to-skin contact, and longer laboring schedules, for example, has been proven.

Even at a moment in which field hospitals have been set up in New York City to reduce the crush on hospitals dealing with COVID-19, there is evidence that patient-centered practices and shared decision-making are at work. Rebecca’s anesthesiologist held up her phone so her husband could watch the birth by FaceTime; she decided with her doctor to keep her baby in the recovery room, and forego use of the hospital nursery.

“Of course we need to keep ourselves and our patients safe when it comes to infection,” says Dr. Chitra Akileswaran, M.D., vice chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Alameda Health System in Oakland, California, and co-founder of Cleo, a resource for working parents. “I think we still have to have a sense of humanity about all of this.”

Some of the current policies would have been unimaginable just months ago for people pondering their birth preferences, but blame for birth disappointment has shifted. It now seems possible to imagine that the birth experience of one person (a woman permitted to labor for longer without interventions to accelerate, say) might have implications for the experience of another (a woman who gives birth in the hallway on a gurney), where it once seemed solely a question of patient autonomy. Hospital policies during COVID-19 have been “formulated with input from the community they serve” and guidance from experts — obstetricians, infectious disease specialists, etc. — says Minkin. In other words, they are constructed in the interest of public health, which didn't seem as obvious before now.

In Ireland, Gosani delivered her third child on March 18. Before the pandemic, she had wanted “kind of a natural birth ... as gentle as possible with very little medical involvement.” After COVID-19 cases began to bloom in Cork, she was worried her doctors and midwives would pressure her to undergo an early induction at 39 weeks.

They didn't. She went into labor on her due date, and her husband drove her to the hospital. There, the hospital’s policies prohibited him from entering the emergency room, where she was triaged; allowed him in the delivery room (a quick, unassisted birth); and did not permit him in the recovery wing. Gosani says her doctor did an amazing job.

As many OB-GYNs do every day. The “medicalization” of birth over the past century has seen infant mortality fall, in part due to commonly criticized obstetric practices. Meanwhile, OB-GYNs are subject to high rates of burnout. In a 2018 Medscape survey, 50% confessed to burnout or depression; 18% identified lack of respect from patients as a stressor, alongside a lack of autonomy (23%), and long hours (43%). A lack of trust ultimately impacts the patient if communication is poor, says Minkin.

The people most at risk in the current moment are not those with the agency to draft a detailed birth plan and enlist a private doula to ensure it is followed, but the population of people who already fare worst in the health system. Women of color die at three times the rate of white women during and after birth, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, and minority patients tend to deliver at lower quality hospitals (New York's pilot program providing doula services through Medicaid aims to address these disparities). Exacerbating the situation, the pandemic has affected public hospitals hardest.

Unfortunately, COVID or no COVID, emergency situations in labor and birth do occur.

There is never a shortage of terrible birth stories, but under normal circumstances it is easy to believe you can act to make sure you won’t be one of them. Expectant parents are undoubtedly looking at birth differently in this moment, and a silver lining may be that patients and obstetric staff finally see themselves on the same side. The current protocols aren't ideal for anyone, including obstetricians. This is not the experience Kate Middleton had in the Lindo Wing. Not only will there be no champagne and high tea after delivery, there may not be enough face masks for all the attendants. The support team you planned on may not all be there in person. And the true villain, it turns out, is not the knife-happy obstetrician, but an overtaxed health care system held up by an army of heroes now putting themselves at risk every day on the job.

A fact of having babies now is that even deliveries that do not require interventions are necessarily medical in a hospital that has been impacted by equipment shortages, bed shortages, and exposure of staff to a mounting pandemic. Thinking of patients in terms of dollar signs seems inhumane until you consider that this is what public health officials do — they determine policies in part by considering the value of a statistical life. Birth is medical as soon as something goes wrong at home and you are relying on a compromised safety net of emergency services to get you to the equipment and specialists who can save your life or your baby’s life.

Pre-pandemic, home birth brought with it a more than twofold increased risk of perinatal death, and the risk of needing a hospital transfer during labor is 23–37% for first-time mothers. Now, “if you develop an emergent situation during a home birth, you wouldn't necessarily get super rapid care for an emergent transfer to a hospital," says Minkin, "and unfortunately, COVID or no COVID, emergency situations in labor and birth do occur.”

"In a time of war people had to make great sacrifices for the greater good," says Dr. Alexandra Sacks, M.D., a reproductive psychiatrist and the author of What No One Tells You: A Guide to Your Emotions from Pregnancy to Motherhood, and acknowledging that can help you process a birth that is not exactly what anyone wanted for you or anyone else. "It may be a nice, comforting image for some people to imagine a future where they can tell their child that they all got through it and that it was a part of this global initiative to protect the public health."

Social image credit: Fabrizio Villa/Getty Images