News

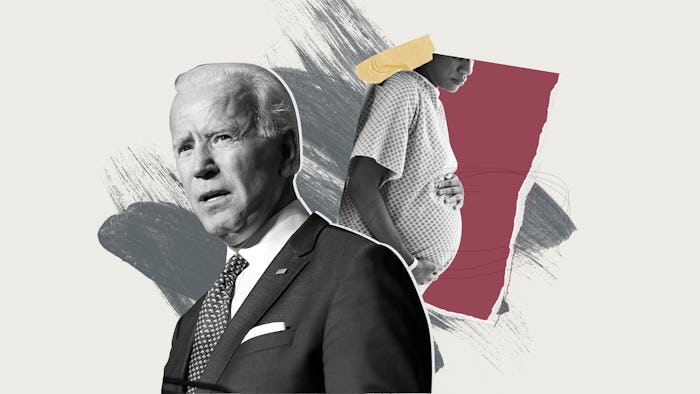

Will Biden's Plan For Reducing Maternal Deaths Work For Black Moms?

Kira Johnson, a Black mother, died from complications of a C-section in 2016. Her husband, Charles, who was recently awarded $1 million by the hospital, says doctors ignored him for hours as he begged them to check the blood in her catheter. "When they took Kira back into surgery and he opened her up, she had three-and-a-half liters of blood in her abdomen from where she'd been allowed to bleed internally for almost 10 hours. And, her heart stopped immediately," Charles told CNN.

Kira became one of the hundreds of Black mothers who die during or within one year after childbirth in the U.S. each year. The statistics are often repeated: Black mothers account for 40% of maternal deaths despite making up about 13% of the female population in the U.S. at any given time. Their deaths are largely preventable.

The overall maternal mortality rate in California declined by 55%, but the racial gap didn’t budge.

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden plans to address this crisis by requiring hospitals nationwide to use California’s maternal care toolkits, which aim to prevent delayed treatment or misdiagnosis of birth complications. For a presidential nominee to push a policy on Black maternal health while campaigning for a general election is new and welcome. It reflects the work of generations of Black women voters, finally recognized as the Democrats’ most dependable voting bloc, as well as that of the activists and journalists who have worked for years to draw attention to the systemic racism that pervades American health care right now, today.

There is just one problem with Biden’s approach: While improving overall maternal mortality rates in California, the maternal mortality rate for Black women in the state remained three to four times that of other mothers.

According to his official campaign website, Biden’s strategy to address the maternal mortality crisis centers on the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC). The CMQCC was formed in 2006 by the state of California in conjunction with the Stanford School of Medicine to confront the rise in preventable morbidity, mortality, and racial disparities in maternal care statewide. Funded in part by the California Department of Public Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the collaborative provides research-informed quality improvement “toolkits” to hospitals. Basically, they train health care providers to be more aware of and responsive to common, preventable birth complications.

The CMQCC's hemorrhage toolkit, for example, includes instructions on performing a hemorrhage risk assessment, techniques for stopping blood loss after childbirth, hemorrhage medications for quick access, and it takes hospitals through how to performing hemorrhage drills regularly to ensure hospital staff can react quickly and effectively.

Between 2006, when the program was implemented, and 2013, the overall maternal mortality rate in California declined by 55%, but the racial gap didn’t budge.

The CMQCC is aware of this shortcoming of the program. In 2019, launching its Birth Equity Initiative to address the ongoing disparity, the collaborative wrote, “The expectation was that widespread adoption of CMQCC’s clinical safety bundles would reduce the gap... Despite the reduction in Black maternal mortality rates, the difference in outcomes for Black mothers compared with all other racial groups has persisted.”

It’s absolutely racism.

The Biden campaign is also aware. “Vice President Biden and Senator Harris are committed to addressing this national health crisis,” Mariel Sáez, women's media director for Biden for President, tells Romper. In implementing the California program nationally, she says, “A Biden-Harris administration will take additional actions to address racial inequities in health care, including expanding access to affordable, high-quality care, addressing social determinants of health outcomes, and diversifying our health care workforce.”

But how will they address inequality and “social determinants” in a way that works where past attempts have failed? How will they expand access when centuries of racism help limit that access? We need a thoughtful, well-articulated plan for doing what policies alone cannot.

“I don’t think that there are really simple policy solutions to the kind of phenomenon where Black people and our concerns are not taken seriously,” says Rebekah Cross, M.A., a health policy research scholar who works at the Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice and Health. Cross says that a multi-pronged approach is required, and one of the prongs is equipping providers to listen to Black women. A 2018 survey published by the California Health Care Foundation showed Black mothers said they weren’t listened to when expressing their fears and concerns. Black women surveyed also reported unfair treatment, discrimination, and rude language from their health care provider, and were more likely to report feeling pressured into interventions.

Dr. Kiarra King, M.D., a board-certified OB-GYN in the Chicago area, says many clients who come to her don’t feel heard by other doctors. When Black mothers’ concerns are dismissed because of the color of their skin, “it’s absolutely racism,” she says. “[Providers] have to make sure they’re taking ownership for each and every patient. Not just the patients that look like them.”

Black-led grassroots organizations advocating for better treatment and outcomes for Black birthing people have offered strategies for doing this. Black Mamas Matter Alliance, for example, offers a toolkit that takes a human rights-based approach to maternal health. In addition to explaining racial maternal health disparities to advocates and providers, it recommends training providers to give culturally competent care, recruiting a more diverse health care workforce, and increasing access to community models of care such as doulas and midwives.

Incorporate strategies like the ones that Black birthing activists have developed — or better yet, use those!

The Black Birth Experience (BBX) aims to educate family members on how to properly support and advocate for their birthing loved one, and also advocates for access to doulas. Brittany Fadiora, a certified doula of 10 years and a founding member of BBX, emphasizes how essential it is for Black women to have a third-party doula. She says because doulas don't work for the hospital, they can "play both sides and be proactive." Studies have found that doula support improves Black maternal health.

Whatever policy Biden ultimately implements if elected, Cross warns against any that places responsibility for fixing poor health care on individual women. “So many initiatives are centered around maternal behaviors. What we need to remember is that this is not a crisis of poor behavior on the part of mothers. It is a crisis of racism at all levels.”

The last piece is real consequences for those who provide Black mothers with a low standard of care. The U.S. does not have a strong record of penalizing those who undervalue and even cost Black women their lives through negligence. “An initiative without teeth doesn’t work as well as it should,” says Nadereh Pourat, Ph.D., a professor-in-residence at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. “If you identify that there’s institutional racism, then you need to have a mechanism for checking to see whether providers have actually changed their behavior.” Pourat says that for those who haven’t, there should be accountability and repercussions.

If Biden does not incorporate strategies like the ones that Black birthing activists have developed — or better yet, use those! — into the California strategy before implementing it nationwide, his plan will leave Black mothers behind again. Would the hemorrhage toolkit have saved Kira Johnson’s life? In an institution where Black birthing families still fight to be heard, perhaps not.

This article was originally published on