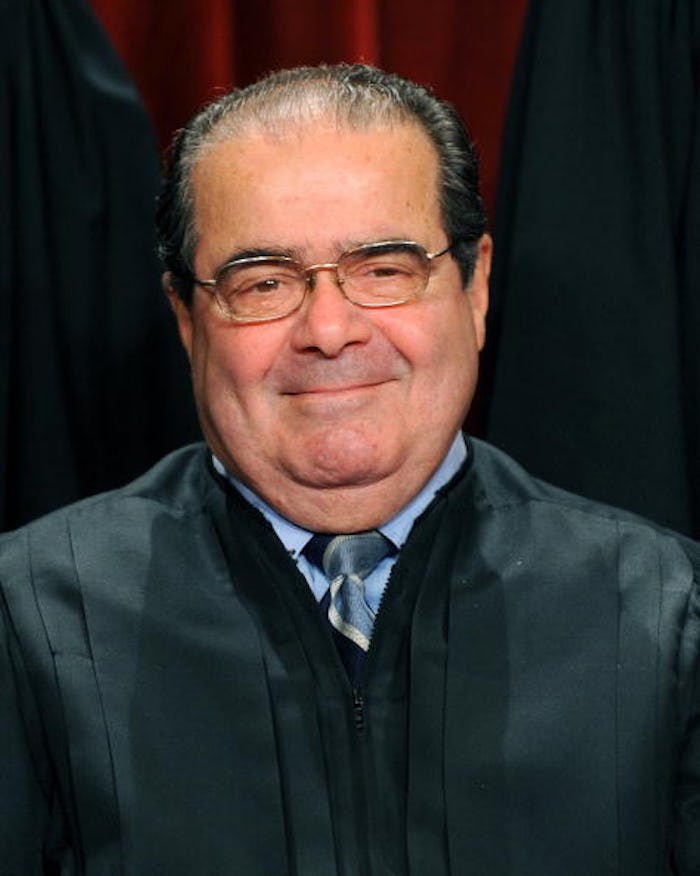

On February 13 on a West Texas Ranch, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia was found dead of apparent natural causes at the age of 79. Appointed to the court by Ronald Regan in 1986, the associate justice defined his 30-year tenure on the Supreme Court as a Conservative and an originalist, who believed the Constitution was not, as is sometimes said, "a living document" whose original intent should be applied to an evolving sociopolitical landscape, but rather that the Constitution is a dead document. As you can imagine, a Justice who believed that the Constitution should be viewed as having relevance insofar as it was put forth 229 years ago by mostly wealthy, mostly slave-owning white men did not often rule to the benefit of women.

Perhaps because of his outspoken Conservatism and larger-than-life personality, Scalia is often seen as the face of what many Liberals and Progressives see as an the increasingly socially regressive Supreme Court. While his personal life teases at more complexity than simply being a Conservative bogeyman — "The judge who always likes the results he reaches is a bad judge," he was known to say; and let us not forget that darling of feminists everywhere Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Scalia were best friends — his voting record as viewed from from an intersectional feminist perspective is, frankly, appalling.

Scalia was often on the wrong side of progress, by most accounts. From abortion rights to civil rights, to marriage equality to healthcare, from corporate citizenship to affirmative action, Scalia was known less for his rulings, and more for the pithy, gasp-inducing one-liners that summed up the disappointment, disgust, and fears of those left-of-center. Arguing in Fisher v. University of Texas, for example, Scalia said:

"There are those who contend that it does not benefit African-Americans to get them into the University of Texas, where they do not do well, as opposed to having them go to a less-advanced school, a slower-track school where they do well."

"Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn't. Nobody ever thought that that's what it meant. Nobody ever voted for that. If the current society wants to outlaw discrimination by sex, hey we have things called legislatures, and they enact things called laws. You don't need a constitution to keep things up-to-date ... You want a right to abortion? There's nothing in the Constitution about that. But that doesn't mean you cannot prohibit it."

So in light of a career abounding with decisions that have either chipped away at the advances of women (such as the repeal of the Voting Rights Act) or prevented them (as in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.), it is tempting for women, feminists, the LGBT community, people of color, and anyone existing within intersections of those groups to give in to our less compassionate, baser nature and join together in a rousing and merry chorus of "Ding-Ding! The Witch Is Dead!"

And loathe though I am to deter anyone from re-enactments of classic musicals, the more important and obvious truth of the matter here is that Scalia's death doesn't somehow "fix" the Supreme Court of its regressivism. It merely creates an opportunity to ameliorate it with a new appointee. The questions now are as follows: Whom will the president nominate to replace Scalia, who will be president when that decision is made, and who will be voting on the presidents nominations?

Scalia's death doesn't somehow "fix" the Supreme Court of its regressivism. It merely creates an opportunity to ameliorate it with a new appointee.

Before Scalia's death, the Supreme Court stood basically evenly divided: Justices Alito, Roberts, Scalia, and Thomas representing the Conservative end of the spectrum; and Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan, and Sotomayor, the Liberal. Justice Kennedy, while more prone to Conservitism, has become increasingly Liberal over the years. He is often seen as a kind of tie breaker; Indeed, many of the Court's most well-known rulings in recent years have come down to a swing vote by Justice Kennedy.

Within moments of the announcement of Scalia's death, Republican and Democratic leadership took their stands on when they thought this decision should be made abundantly clear: Republicans want to wait until after the 2016 election...

...whereas Democrats want the position filled right away.

Naturally, there are also GOP hopefuls are keen to wait, potentially reserving the honor of nominating the next Supreme Court Justice themselves.

Of course, this all makes perfect sense. Conservatives are willing to roll the dice and hope that, by the time the next president takes office, he will be one of their own, replacing Scalia with another Conservative and maintaining what has been the status quo. Even if a Democrat takes the White House again in 2016, they are likely in no worse a position than they are now. Liberals, of course, would rather a nominee appointed by President Obama, who has already given us the likes of liberal-leaning Justices Kagan and Sotomayor. But Democrats have an added challenge here: confirmation of a nominee.

Whom will the president nominate to replace Scalia, who will be president when that decision is made, and who will be voting on the presidents nominations?

While the longest Supreme Court confirmation process took 125 days (the honor goes to Brandeis, the nation's first Jewish justice) and Obama has almost an entire year to get someone through, the fact that the stakes are so high here does raise the question as to whether Republicans on the Senate Judiciary Committee will obstruct anyone Obama suggests.

So what does Scalia's death, ultimately, mean for women? Yes, it does provide opportunity and hope that a post-Scalia court will be more inclined to recognize women's rights as fundamentally needing Constitutional protections. But his death also highlights the oft-touted yet under-practiced importance of voting. Not just in presidential elections but all elections. Because Senators with the power to confirm or reject the President's nomination were voted upon by you... actually more likely they weren't. In 2014, voter turnout was at a 72-year low with a mere 36% of eligible voters heading to the polls. What I take away from this is, yes, we have a chance now... but we could have done so much more to help our odds.