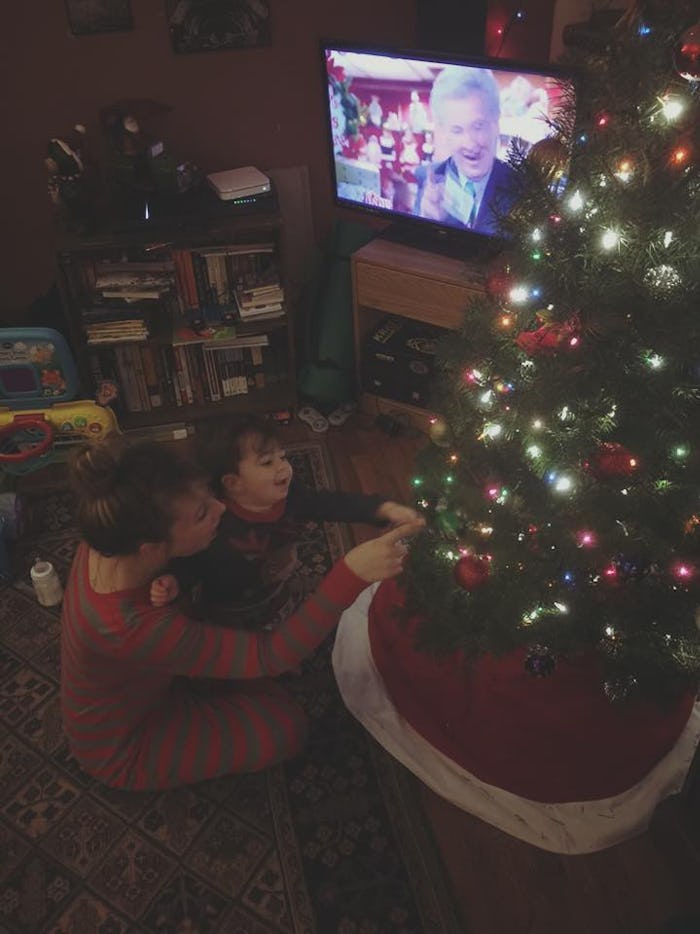

I'm sitting on the floor in front of our extremely lit, slightly over-decorated Christmas tree. My son has just handed me a book before turning around, backing up and plopping his tiny body into my lap. I begin to read about Sesame Street's Grover and his infinite adventures before looking up at my partner, who is sitting on the couch and smiling at us. I smell the fresh pine of the tree we cut down the week before, and while I read another sentence out loud, I'm simultaneously thinking about the cookies I'll be baking and the next holiday movie my family will snuggle up and watch together.

And it is in this seemingly perfect, serene moment that my thoughts turn to that of my father.

I grew up in an abusive environment, both physically and verbally. My father was violent and angry a good 70% of the time, and my family never knew which version of "the man of the house" we would be getting each day until he walked through the door after work. My first memories are of my father beating me outside, on our back porch, with such unapologetic force that I soiled my pants. I was five years old. For the rest of the time I spent in my childhood house, I was a version of that little girl: scared, nervous, and forever wanting a father who didn't exist. Sometimes, even now, I am still that little girl.

My brother, who is a much stronger person than I am, cut my father off after he threw my mother down our stairs and broke her ankle in two places. I had a harder time completely cutting him out of my life. I struggle to adequately explain my longing, to those who can't or don't understand, but a part of my heart holds tightly to a specific ideal. I have this picture of a father-daughter relationship forever engrained in my brain, and then poked by other, real pictures and posts of friends who have that relationship with their fathers, and I just can't bring myself to completely let go of it, even though it is but a shadow of a now-impossible future.

And that shadow has remained. While having my father out of my life is no doubt a healthy decision, I wish it wasn't such a painful necessity. Now that I have a son who loves to sit on my lap and listen to me read, I sometimes think about the undeniable fact that he will grow up without ever knowing his maternal grandfather, and when I do, invisible tears fall from my otherwise smiling eyes. I think of the moments when he wasn't angry or violent, but loving and (usually) resentful, and I silently yell at him. Why couldn't you have been like that all the time? Why couldn't you have been the dad who always made me feel safe, instead of scared? Why?

I look up and imagine my father sitting in the empty chair next to where my partner is, and see him playing with the grandson he'll never meet. I wish that he could buy him presents and comment on his magical smile and that I would feel comfortable letting him hold my son at all. I've watched as my partner's father has played with and held and even napped with our son, and I become sad and jealous and wishful, all at once.

I think about the family gatherings we could have had, where my father could have cooked for my son and my son could have spent the remainder of the year begging to visit grandpa so he could cook for him. I can almost smell all of the Puerto Rican fixings he used to cook for Christmas, and my heart starts to lean on the inside of my rib cage; heavy that my son will never smell those smells.

And that is what the holidays are like without a father who isn't far away or dead or deployed, but necessarily absent. It's a cruel mixture of happiness, relief, sadness and yearning. I want the things I know I can't have, not only for myself but for my son. I want the mirage that is just out of hand's reach and even though I know I will never touch it, I continue to crawl through the sand, asking for water from a man who — in my world and of my own choosing — no longer exists.

I know my father made his bed with angry fists and toxic words, but I ache for all he can no longer have. I envisioned him sitting alone on Christmas Eve, eating a meal that should be for four but is now just for one, flipping through channels and pained with loneliness. I see him next to a small tree with minimal presents underneath it, because neither his estranged ex-wife nor son nor daughter send him anything for the holidays. I think about all the grandchildren he has that he has never met (not just my son) and how happy they will be, opening presents from every family member except him come Christmas morning.

Images: Courtesy of Danielle Campoamor(3)