Life

Why I Threw Out My Daughter's Developmental Testing Reports

Given my 6-year-old daughter Esmé’s disabilities, developmental testing — the process of assessing a assessing a child's developmental skills using standardized testing methods — is very much a part of our lives. These tests are a requirement for my daughter to qualify for the services that support her, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and special education. But over the years I have found that developmental testing does not offer much insight into Esmé’s abilities. And I am not the only one to notice — professionals also question the efficacy of standardized testing for children with severe disabilities. This year, our experience with testing reached an all-time low, and there was really only one place to file it: in the trash.

Recently, Esmé took part in school district developmental assessment by a school psychologist — a requirement of her Individual Education Plan (IEP). Despite my skepticism about developmental testing, I was a bit excited for the evaluation. I expected her to score unimaginably low in most areas, but I was keen to see the recent advances in her abilities reflected in the report. You see, while Esmé doesn’t speak or walk or brush her own teeth, on good days, she is now reading full sentences, doing simple math, and using word cards to communicate. And although Esmé demonstrates these skills variably, her regular therapists absolutely agree the skills are there.

Read: I am not hallucinating these abilities.

When the evaluation from the school psychologist arrived, it reflected very few of these skills. It also placed Esmé’s cognitive skills at the level of a 6-month-old. I may be out of pace with typical early childhood development, but I’ve never met a 6-month-old who, when asked what continent she lives on, can accurately select “North America” from an array of choices.

As I read through the report, I found myself wondering why it is that these assessments work so hard to identify deficits for the purpose of classification, but do not also uncover or report highlights, such as Esmé's reading skills. Deficit-based thinking is problematic for many populations of children, but perhaps especially so for children with severe disabilities. Why are professionals not presuming competence? The disappointing default is to acknowledge abilities only when they fit easily on a bubble sheet.

Esmé has a series of genetic mutations that result in her overall fragile health, and manifest as a visual impairment, movement disorder, and lack of verbal communication. These challenges can make it difficult to get a sense of her abilities because she cannot always participate in standard tests to show simple skills, like cause and effect. For example, Esmé regularly refuses to participate in a particular oft-repeated developmental test involving a flesh-colored plastic hoop tied to a thin white string. In this test, the child is supposed to demonstrate her understanding of cause and effect: the hoop is placed outside of the child’s reach and the child is supposed to pull the string in order to bring the hoop within reach.

I mean, what is more motivating to a 21st-century child than the unending joy and overwhelming excitement of finally grasping that plain beige plastic hoop? I’m still not certain Esmé can even see the thing, but if she can, it doesn’t light up and play music, so she is not interested. Either way, she refuses to pull a string and prove her problem-solving skills. Therefore, she receives zero points.

However, Esmé, my three-foot child who cannot stand independently, has been known to wait until I step out of sight to crawl across the room, pull herself onto the seat of a chair, and use her teeth, fingernails, and gravity-defying determination to drag herself to stand against the back of the chair, just so she can procure her iPad from a windowsill. Seems like cause and effect to me, but they don’t give developmental problem-solving credit for that, apparently.

I’ve asked — several times. So, while this is clearly a higher-level skill, since the psychologist did not observe it and it does not fit on a bubble sheet, it is not relevant to the official assessment my child's abilities.

Through conversations with Esmé’s longtime therapists, I have come to understand that this irritation with standardized developmental testing is not mine alone. Esmé was around 2 years old when I first realized this was the case. For months, this therapist had witnessed Esmé identifying flashcards of animals and household items. She knew how bright and focused Esmé could be. However, when it came to doing standardized testing for Esmé to judge what objects she recognized, the tests had to be done in a very particular way that was not conducive to Esmé's visual and physical challenges.

I watched as the therapist tried to use a testing booklet to showcase Esmé's ability to point to an object in an array. Esmé couldn’t do it. Had we cut up the book and presented the images as cards on the floor, we knew she’d have some success. I knew this therapist well, and she was always a calm, steady presence, but a half hour into the testing, she turned to me with clear frustration on her face. She told me that she was angry that the materials she had to work with couldn’t give Esmé credit for her knowledge and skills.

The therapist and I knew that with a child like Esmé, there is no chance that she won’t qualify for services like speech and physical therapy. There is no question of her needs; she is significantly delayed in all aspects of her development. However, Esmé also has pockets of skills that are as important to understanding her as her delays — if not more so. For example, knowing that Esmé can read, but not speak, can alter the methods used to aid her in communication. This therapist looked at my child and saw someone complex, interesting, and competent — as are all humans — and wanted to see the testing reflect some of that. It seemed important to our therapist to be fair to Esmé. It seemed important that her record accurately reflect who she is and what supports she needs. It seemed important to at least attempt to test for the underlying ability that a set of skills exposes.

This most recent round of tests with the school psychologist felt important to me, because it was the first assessment we’d had in some time by someone who had not been working directly with Esmé. Given that we are heading into a discussion about her placement next year, I felt like a lot hinged on this assessment, and I have been struggling with the responsiveness of our school district, which had failed to provide the nursing required for Esmé to physically attend kindergarten this year.

Given Esmé’s emerging skills, I hoped that finally the conversation could shift toward something that Esmé is skilled at doing — learning. And her ability to learn seems especially important when I am talking with the school district in charge of educating her. The conversation could have become how to open a world up for a child whose world has been disproportionately limited by her own body and brain function. In Esmé’s case, the way to reach her may be through her curiosity and reading … as well as music and light up toys.

Instead, with this report, the topic remained focusing on what she lacks in some ablest notion of what a 6-year-old should be doing, not what this particular 6-year-old is doing — namely, reserving the energy she’s saved not doing all the things "typical" 6-year-olds are doing in order to be able to answer a question about what province in Canada her father is from (New Brunswick).

Thanks to our luck with exceptional therapists who are focused on seeing and understanding Esmé, not scoring her, I have also come to understand many of these tests as a kind of bureaucratic hurdle we need to jump over — together. I get less worked up than I used to, certainly, when I see yet another line in yet another test assigning a ridiculous age range or percentile to my daughter. And our therapists are always careful to supplement their testing with detailed narratives that explain the things standardized tests cannot highlight.

Yet I believe more than ever that such evaluations need to be able to better serve the complexities of children like Esmé. I see them called for by other parents of children with various needs, as well as by many of the professionals who are dedicated to working with them. Improved assessments for such children is an absolute necessity because, as I well know, people are far too fast to dismiss the abilities of children who are non-verbal or who lack motor skills, rather than presume competency.

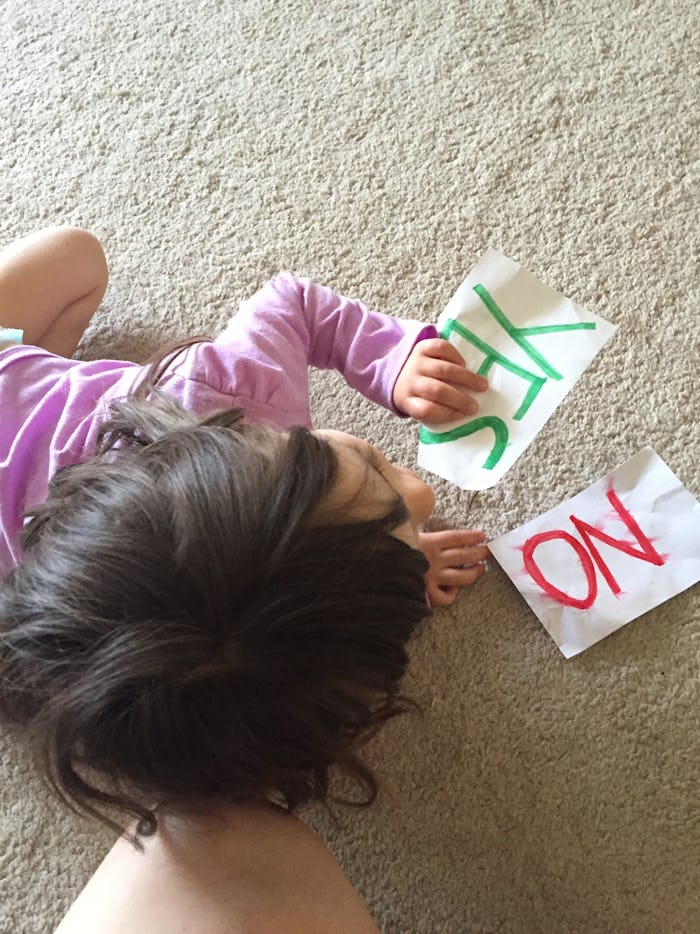

This is true for the little girl who met Esmé on a playground and, upon hearing that Esmé did not speak, implied that she must be "stupid." For the well-intentioned mom who asked about Esmé at Starbucks and then explained that she “had the opposite problem” because her son was gifted. For, apparently, the school psychologist who stated that she didn’t think my daughter was using her “yes,” “no,” “help,” and “all done” cards meaningfully — something she’s done for almost two years — because she put them in her mouth after selecting them. Esmé puts everything in her mouth (except for food), but that doesn't mean her selections are unintentional.

It becomes an important question of advocacy that my daughter's competencies of all varieties are carefully recorded and reflected in the kinds of documentation that will determine school placements and therapies. This kind of documentation matters because it follows children to places where their advocates may not be able to speak up for them. It can make all the difference in a child being adequately challenged, understood, and encouraged or not.

But it also matters because this is “expert” communication with parents who may not look for such competencies without encouragement, or who may feel uncomfortable adamantly defending what they believe about their child’s abilities in the face of reports like the one I just received. It matters because I firmly believe there are many children like Esmé, who understand far more than they can communicate. For these reasons, the limitations of standardized testing for a child like Esmé cannot be dismissed as merely paperwork. When a child is limited in so many ways already — by communication skills, the simplest of body motions, and responsiveness to social cues — being deprived of a proper and supportive education is an immeasurably grave loss.

So, for now, I will continue to carefully document my own understanding of my daughter’s abilities while being, as always, clear-eyed about her very real challenges. For now, I will continue to encourage other parents to insist that their children be seen as full, complex individuals and to follow their instincts about their child's abilities. For now, I’m going toss out that report and return to the hard work of looking to my daughter to tell me who she is and what she needs.

Watch Romper's new video series, Romper's Doula Diaries:

Check out the entire Romper's Doula Diaries series and other videos on Facebook and the Bustle app across Apple TV, Roku, and Amazon Fire TV.