Parenting

The Mystery Of This Boy We Made

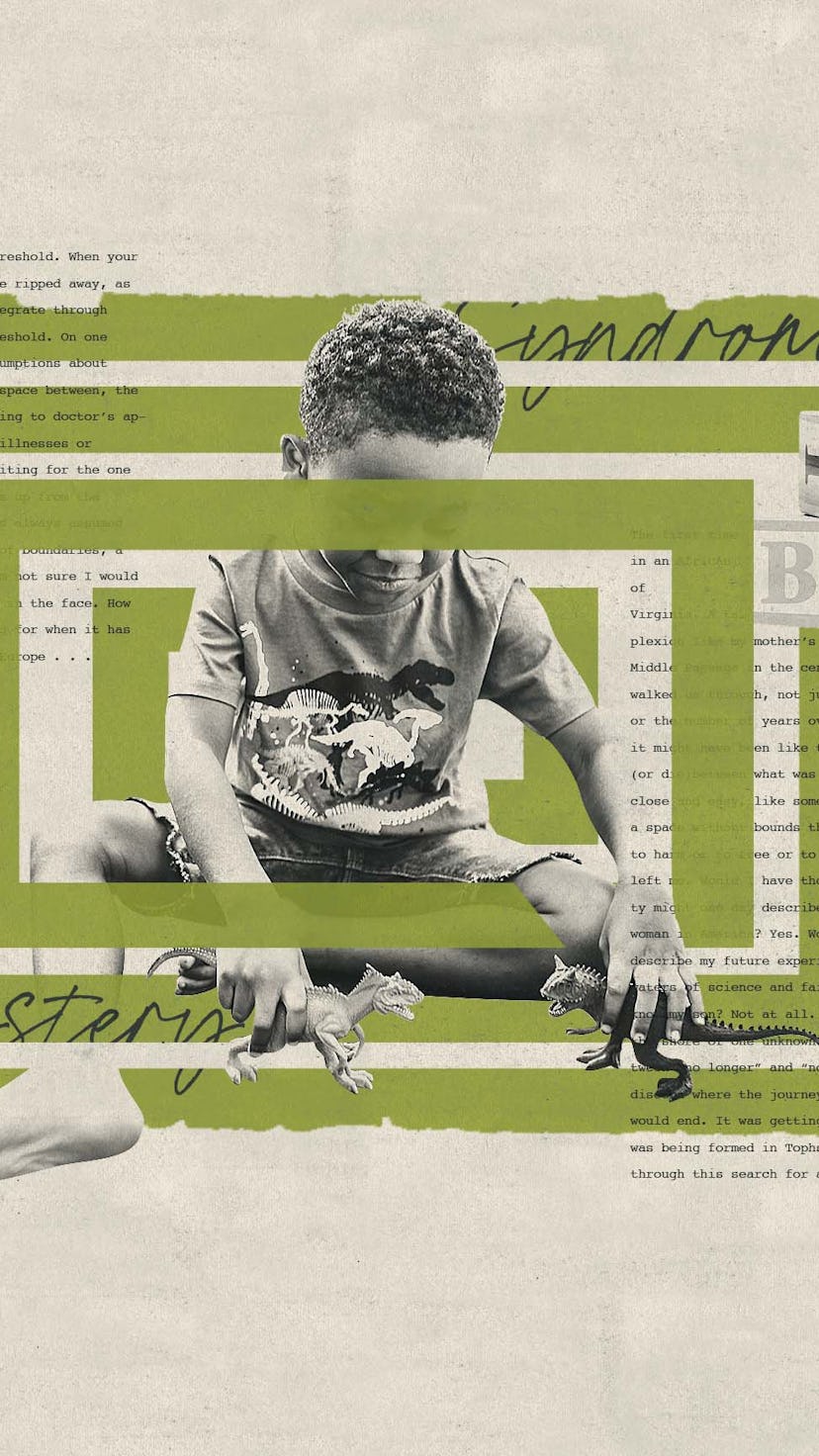

What did it mean that our son looked small but fine on the outside yet was struggling to communicate, to understand?

Because I live as though credit cards are just generous debit cards, my husband Paul scheduled an appointment for us to meet with a life insurance agent. As we sat in a bland boardroom with large windows, she asked questions about our children and warned us that because our son, Tophs, had a growing medical record that included hypoglycemia, growth failure, developmental delays, and an elevated enzyme level, he might not qualify for the highest level of coverage. She presented three levels, named after superheroes, which seemed absurd. As though health challenges rendered a person less powerful or deserving of praise. But what I remember most from that meeting was the talk the agent and I shared, mother to mother, on our way out of the room. Her son, a few years older than Tophs, also struggled with delays, his name somewhere on that long list to see the same developmental pediatrician.

“It takes so long to get in,” she said as we moved toward the elevator. I didn’t dare mention our pediatrician had gotten our appointment bumped up. “I hope everything works out for your little guy.”

“Thanks. I just can’t wait to finally get some answers.”

We entered that doctor’s appointment as a family. While we wore regular clothes, I felt like a mom preparing everyone for picture day. Was the diaper bag packed? Did Tophs have snacks for the wait? Would Eliot be a help or a distraction as the doctor assessed Tophs? With Paul there, at least I had options if Eliot needed a break. I could relax a little. But Tophs hadn’t napped well that afternoon and was in no mood to please the first doctor who entered the room, a department fellow, who would perform the first round of tests.

What she couldn’t read in his medical records, we told her: “Difficulty with ‘wh’ questions. Hard to engage in conversation. Seems best at memorizing songs or things he’s seen visually.”

We had evidence from his preschool teachers, too, who had noticed more as the year progressed: “Doesn’t interact with peers at school, will occasionally play with a nonverbal student in his class. Gets frustrated when he can’t communicate clearly.” But it wasn’t all delayed, all what he couldn’t do. “Likes to cuddle, engages with family, makes good eye contact.”

The fellow, as lovely as she was, stood between us and Dr. Perry, the developmental pediatrician we’d come to see. How much should we tell her? Would we have to repeat it all? Did she know how to assess him? When you wait months for an appointment, longer for answers, you need everything to go perfectly. So what I remember most about Tophs’s time with the fellow is what he couldn’t, or refused, to do. I both wanted him to struggle enough for her to get an accurate picture and nail the tests I knew he could, like stacking blocks. When he stacked only three or four on the table, I wanted to jump in and regulate. He could easily stack ten.

But if I said, “He usually stacks more,” I’d be the mom who cares about performance over everything. So I let her prompt him when she wanted, let Tophs refuse when he wanted, hoping he wasn’t the first kid they’d seen who’d missed an afternoon nap.

When Dr. Perry entered, wearing slacks and a button-down, he carried a small black case that resembled a mini backgammon board. Somehow I believed everything we’d need was packed inside. He sat down, opened the case, and asked Tophs to put the various pieces into place. In the notes, he wrote that Tophs could “reverse the form board.”

I can’t remember exactly what he grabbed next—was it a plain piece of white paper or a small dry erase board—and, thankfully, I didn’t know the gravity of the test until it was over. He drew a horizontal line. “Can you draw this for me?” he asked. Tophs did. Then he drew a vertical line. “How about this?” Tophs’s lines were shakier, fainter, made with a fisted grip, but they were there.

“Well, that’s good news,” Dr. Perry said. “The fact that he was able to copy those lines means his intelligence is at least on the low side of average.”

Had he just handed us a life vest or shot a hole through our boat? Or both?

He finished examining Tophs in about ten minutes and then sat Paul and I down while Tophs and Eliot played. “When I look at his records—the poor growth, carnitine deficiency, history of hypoglycemia, and now global developmental delay—he’s got something. We’re just not smart enough to figure it out yet.”

What if the world was closed off to him in ways it remained wide open to me?

Something. Global. Yet. This wasn’t a fluke. Tophs had stumped the best. I processed this much before the tunnel started to narrow.

“Given your levels of education, he’s certainly an outlier.”

Outlier. Like begets like. Each seed after its own kind.

“I think he should see Genetics again for whole exome sequencing. And he should have every new wave of genetic testing that becomes available. Science is moving so fast, and what we don’t know now we might know in ten years. Maybe one day somebody in Europe will discover the Christopher syndrome.”

Every new test. Europe. My boy as a syndrome.

And then, as the conversation wound down, “If he were my son, I’d go ahead and schedule a brain MRI.”

What will they find?

As I sat across from Dr. Perry, I heard “outlier” as a painful marker of deficit. What did it mean that our son looked small but fine on the outside yet was struggling to communicate, to understand? What if he was lonely or frustrated or scared and couldn’t tell us? What if the world was closed off to him in ways it remained wide open to me? This type of limitation was not what I’d imagined for my child. And the painful path between mystery and atypical, which was really no path at all, was not the one I thought I’d travel.

The first time I heard the term liminal, I was 18, sitting in an African American Studies 101 class at the University of Virginia. A tall and slender Professor Penningroth, his complexion like my mother’s relatives, had written the words Middle Passage in the center of a black chalkboard. He walked us through, not just the number of Black bodies taken or the number of years over which they were stolen, but what it might have been like to be yanked into a void. To live (or die) between what was and what would be.

The concept felt close and easy, like something I’d always known. The idea of a space without bounds that held within its hull the power to harm or to free or to form—that idea has never completely left me. Would I have thought as an undergrad that liminality might one day describe some of my experiences as a Black woman in America? Yes. Would I have guessed liminality might describe my future experiences as a mother, wading through waters of science and faith, in search of the truest way to know my son? Not at all. And yet here we were, drifting from the shore of one unknown to the next. Caught somewhere between “no longer” and “not yet.” It was getting harder to discern where the journey had begun and where, if ever, it would end. It was getting harder to see what, if anything, was being formed in Tophs, in me, or in us as a family through this search for answers.

I tread water while going to doctor’s appointments and Googling, while noticing illnesses or quirks or developmental delays, while waiting for the one doctor on the right ship to come scoop us up from the depths.

When Tophs was born, I knew the justice system might unjustly place limits on him one day. Limits from the outside, from racist seeds that grew slavery and Jim Crow and the verdicts for the Central Park Five—those, while horrific, made some sense to me. Even limits from within, if they looked like anxiety or depression—illnesses that ran through many families, including my own—would not have surprised me. But the idea that wrapped within this boy I’d grown in my womb might be wrinkled genes that would make life harder for him? No, not that.

Liminal comes from the Latin word for threshold. When your life, your customs, your expectations are ripped away, as in the case of slaves, or if they disintegrate through grief and mystery, you stand at this threshold. On one side, I see the disintegration of my assumptions about myself, motherhood, my children. In the space between, the space of not yet, I tread water while going to doctor’s appointments and Googling, while noticing illnesses or quirks or developmental delays, while waiting for the one doctor on the right ship to come scoop us up from the depths. On the other side, who knows? I’d always assumed the other side was an answer, a new set of boundaries, a new territory to navigate and accept. I’m not sure I would know the other side now if it slapped me in the face. How do you recognize the thing you’re looking for when it has no name, no shape? Some-day-some-one-in-Europe . . .

This space can be relentless in its power to hold my imagination captive, to dash what’s beautiful and true to pieces. Because as I sit across from the doctor and hear “outlier,” as I push off into the deep, I do not think about the way Tophs wakes up early one morning to put together a puzzle all by himself. Nor how he intuitively cups my face in his hands and gazes into my eyes. I cannot yet know he is capable of ordering a metal yo-yo off Amazon without any instruction. Because Tophs will think about and do things we would never think of or be able to do at such a young age—or ever. Outlier.

Somehow, these truths deserve to make it to the other side, even if my hands are heavy with doubt. Moses instructed the Israelites to remember the words of the God who had delivered them from slavery: “Impress them on your children. Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up. Tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Write them on the doorframes of your houses and on your gates.”

If the great doctor never comes along in his great boat, if I never get to the other side with newly hewn doorposts, I want someone to find me. I want them to see every dream for Tophs stamped across my forehead, the names of his gifts written on my forearms.

An excerpt from Taylor’s memoir This Boy We Made: A Memoir of Motherhood, Genetics, And Facing The Unknown, which you can buy today!