traps

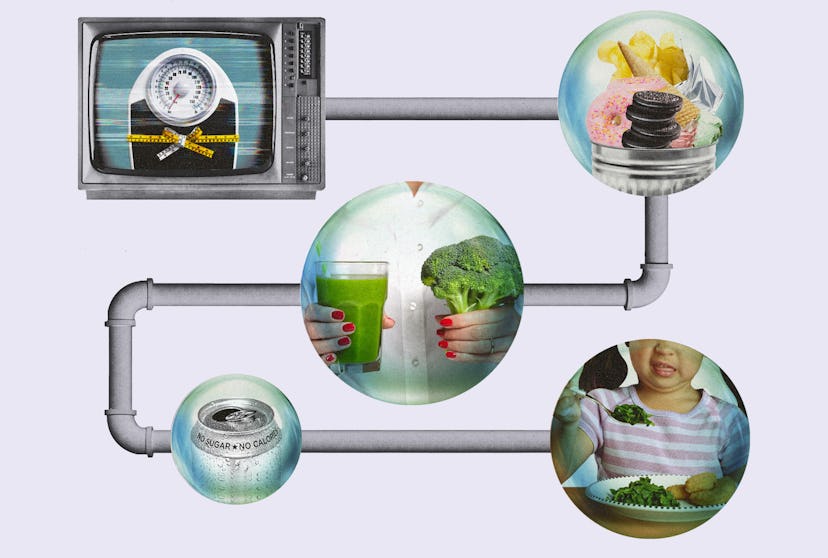

Trying To Raise “Normal” Eaters After A Lifetime Of Diet Culture

Precious few of us show up to parenthood with a glowing relationship with our bodies. How do we raise kids who do?

When Sarah’s sons were growing up, she loved cooking family dinners most nights. Unlike a lot of her friends, she didn’t have to worry about picky eaters rejecting what she made. David, now 21, and Finn, now 18, were big kids who grew up to be “huggable linebackers,” as Sarah puts it. They are both, like her husband, Chris, over 6 feet tall. And they were always hungry. Extended family members and friends offer a kind of benign amusement bordering on pride when it comes to the boys’ size and their “manly” appetites. A favorite family story is the time a friend suggested Sarah use a frozen bagel to soothe baby David’s sore gums — and at not even 1 year old, he ate the entire thing. They are both foodies, especially Finn, who spent the summer before 11th grade at cooking camp in New York City, learning from chefs and eating out at cool restaurants. More recently, during Covid, he was the family member who bought a sous vide machine and got super into baking sourdough bread.

But for her own part, Sarah spent much of David and Finn’s childhood quietly panicking about how much and what they ate.

“I would always hesitate if I was making something I knew they really loved,” says Sarah, now 52 and a longtime attorney on the East Coast. She recalls measuring out pasta and planning not to have leftovers. “I would think, ‘Well, they like this so much, maybe I shouldn’t make too much of it,’” she explains. “I’d try to make ‘just enough.’ Whatever that means.” Sarah had other strategies, too, all designed to subtly enforce a degree of portion control on her ravenous children: Potato chips were only allowed once a week. Hamburgers and fries were OK to order in a restaurant but not the kind of food they ever had at home. When the boys clamored for ice cream, Sarah bought a box of little Popsicles instead of the pints of Ben & Jerry’s they craved. “Most of it was about: ‘No junk food, no sugar. If you’re hungry, have an apple and a piece of cheese,’” she says. “I always said, ‘No way am I bringing that junk in the house because either I’ll eat all of it or they will.’” These rules were familiar to Sarah. And so was her boys’ frustration with them. “Growing up, there was a clear difference between my house and my friends’ houses in terms of the kind of food available,” she says. “I hated it. And then, I made it exactly the same for my kids.”

“I wanted to fix it for them,” she says. “I wanted to teach them some magical set of skills so they would not be fat. I wanted it to just be eating for them. But I had no idea how to do that.”

Sarah’s parents were lifelong dieters, perpetually starting and restarting Weight Watchers, and theirs was a house of cut-up vegetables and no desserts. Home was where Sarah learned that bananas were too fattening, and the so-called right amount of peanut butter to put on a sandwich. She describes her mother as “more of a vanity dieter,” a size 12 to 16 who was forever striving for what she considered true thinness. But her father lived in a larger body his whole life, reaching 400 pounds at one point. “Family members still talk about the time he ate an entire cheesecake in one sitting,” Sarah says. It’s a painful memory. As is her own memory of being 8 years old and reveling in eating an entire plate of french fries in a restaurant — only to be reprimanded by both of her parents. “Shortly after that, I wanted a toy at the store and my mom offered to buy it for me if I lost 5 pounds,” she says. Sarah responded to their restriction by sneaking food at night; she remembers eating slice after slice of Pepperidge Farm white bread while watching TV.

But Sarah was also acutely aware that she was “the fat kid” in her grade, and she turned to her mom frequently for advice on losing weight. At 16, she, too, joined Weight Watchers and lost a significant amount of weight, only to regain it a few years later in college, when her mom died unexpectedly. “My dad really fell apart after that,” Sarah says. Still grieving, she found herself in a caregiving role until her dad died as well, just a few years later. Throughout that strange, sad time, Sarah beat herself up for failing at diets. “Now when I think about all the stress eating I did as a college student or law student, I realize, ‘Oh, there was a lot of emotional stuff going on.’”

But when Sarah had her sons, she was still dieting, and still blaming herself when a diet didn’t work. She knew enough to know she wanted better for her boys. “I wanted to fix it for them,” she says. “I wanted to teach them some magical set of skills so they would not be fat. I wanted it to just be eating for them. But I had no idea how to do that.” And so, history began to repeat itself.

When the kids were little, Sarah periodically caught them sneaking food. Once, when David was 12, and Sarah had allowed a bag of Oreos into the house, she saw him taking four in the middle of the day and was horrified. “He was like, ‘I’m hungry, and we have Oreos! Why is this bad?’” Sarah didn’t know how to articulate it to him. A few years later, when Finn was 14, he asked Sarah if he, too, could go on Weight Watchers. “I said sure!” she says. “And then I saw him so clearly frustrated with the whole thing.”

At first, Sarah was frustrated by his frustration. “He’d say something like, ‘I’ve been good all week; I can have fries,’ and I don’t think there was a lot of shame, which sort of stunned me,” Sarah says. Her version of dieting didn’t allow this concept of “cheat days” for balance. After all, her version of dieting didn’t include balance. “I think my reaction was, ‘Really? You don’t feel bad about those fries?’ Could we have a little bit of perfectionism about this?” Finn withdrew. Food and weight became giant no-fly zones in their family life. And Sarah started to wonder about what, exactly, she was passing on to him. She knew her compulsion to monitor and comment on her sons’ eating habits and bodies was putting distance between her and them.

We’re not just unhappy with our bodies or our relationship with food — we’re unhappy that we’re unhappy.

Precious few of us show up to parenthood with a glowing relationship with our bodies. And moms and other parents and caregivers socialized female are uniquely vulnerable to these struggles. A 2020 study by British researchers found that 15.3% of women will have had an eating disorder by the time they get pregnant. In a previous study of 739 mothers-to-be, the same researchers found that while only 7.5% of the women met criteria for a current eating disorder, nearly 1 in 4 reported high levels of concern about their weight and body shape. And while some (though not all) women experience pregnancy as a reprieve from weight anxiety, we are often then whiplashed into an even more fraught place with it after giving birth. Nonbiological mothers and stepmothers struggle, too, because parenthood can so completely superimpose itself on our previous identities and lifestyles — all of which shows up on our bodies.

And here’s the thing: We’re not just unhappy with our bodies or our relationship with food — we’re unhappy that we’re unhappy. We’re sure our angst means that we’re destined to pass these same anxieties on to our children. We worry that we’ll teach them by example to fear their bodies in the same way we do, or to believe that a woman’s value is her body.

We arrive at this fear honestly. Mothers have always been blamed for our children’s bodies. We are blamed when they eat the wrong way. We are blamed when they are too big, as we have seen repeatedly through the moral panic of the “childhood obesity epidemic.” And we are blamed when children themselves start to fear fatness. The early scientific literature on anorexia is littered with references to “abnormal mothers,” who cause their children’s eating disorders through “dominant and intrusive” or “scolding and overbearing” parenting styles. Such determinations were not evidence-based. In a 1978 review article titled “Current Approaches to the Etiology and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa,” a psychology researcher named Kelly Bemis described these conclusions as “impressionistic and speculative” due to “the virtual absence of con- trolled studies.” But the lack of empirical data on the role of mothers did not stop researchers (including Bemis) from continuing to speculate that children with anorexia, particularly boys, must suffer from “pathological mothering.”

That phrase comes from a 1980 case study published in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease by David Rampling, then a psychiatrist at Hillcrest Hospital in Adelaide, Australia. Rampling’s paper analyzes the anorexia of “Peter B.,” a 28-year-old music student, primarily through Peter’s relationship with his “nervy” mother. Rampling blames Peter’s mother for her grown son’s condition because when he interviews her, she does not remember having written a letter sent to Peter’s doctor about his feeding struggles as a toddler, 25 years earlier. That letter is included in the case study and explains that during Peter’s early childhood, his mother was raising three children, all of whom had complicated health concerns, while also caring for an elderly father almost single-handedly. “I was ordered constant rest myself by a doctor some months ago, but afraid with the three children, my husband and now my father to do for, I don’t get time for rest,” she wrote in 1950, though it’s a sentence too many mothers today will relate to profoundly. But Rampling seizes on inconsistencies between the 1950 letter and his interview with her in the late 1970s, when she recalls Peter’s sister having more feeding troubles than he did. Rampling concludes these lapses in memory demonstrate her “denial” and unreliability as a parent. Rather than, I don’t know, more than two decades of sheer exhaustion? Rampling doesn’t interview Peter’s father, and I would bet both of my children’s college funds that he would have remembered even less about Peter’s childhood eating habits. But in the 1970s and all too often today, we don’t pathologize fathers for being unreliable narrators. We expect it.

We still haven’t found a way to talk about the fact that mothers do influence our children on food and weight without blaming and stigmatizing us for that influence.

Indeed, early eating disorder research either ignores the existence of fathers altogether or views them as passive and uninvolved. “The prevailing belief, which stems from Freud’s theory of psychosexual personality development, was that any psychological illness was the fault of the mother,” says Jennifer Harriger, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Pepperdine University who studies body image and eating disorders. “But the early research doesn’t provide any empirical support for this.” Nevertheless, mother blame became the foundation of early anorexia treatment, with patients regularly cut off from their families in ways we know now to be deeply traumatic. This didn’t begin to shift until the late 1990s, when a psychology researcher named Kevin Thompson developed what’s known as the Tripartite Influence Model, which explains disordered eating and body dissatisfaction as the result of intersecting influences from parents, peers, and the media. Parents (all parents!) play a role — but it is the combined and cumulative impact of each of these forces, along with a child’s genetic predispositions, that determine whether they will develop an eating disorder. Or simply struggle sometimes, in that subclinical, garden-variety way that we all struggle to have a body in this world.

But if there is a downside to this more recent shift, it’s that we still haven’t found a way to talk about the fact that mothers do influence our children on food and weight without blaming and stigmatizing us for that influence. The early researchers who analyzed Peter’s mother and other mothers of the first generations of people diagnosed with our modern definition of anorexia completely ignored the ways in which those mothers were victims of the same pressures they were accused of inflicting on their children. Peter’s mother parented young children during the 1940s and 1950s, a time when her own mental health was nobody’s priority, when her body was barely her own, and when her entire identity would have been wrapped up in her motherhood.

Eighty years later, women’s roles in society have transformed, and yet maternal mental health remains one of our lowest priorities. We still chafe against the expectation that our personal identities should be subsumed by motherhood. And our cultural definition of motherhood has become even more rigid, in some ways, as our other freedoms have increased. Mothers today are much more likely to work outside the home, and yet in 2019, we spent an average of 1.43 hours per day caring for our children, up from just 54 minutes per day in 1965. In comparison, fathers in 2017 invested an average of 59 minutes per day on such tasks — up from just 16 minutes in 1965 but still a long way from equal.

Mothers also continue to perform the majority of our households’ “mental load,” or cognitive labor; all the behind-the-scenes work of writing grocery lists, buying snow boots, choosing pediatricians, making appointments, and signing kids up for soccer teams and dance classes. These efforts are both essential and yet so invisible that many researchers studying parental time use don’t even include the mental load in their tallies. In a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, for example, we learn that 71% of mothers do all the grocery shopping and food preparation for family meals, but the researchers didn’t ask about specific mental load tasks like planning menus, making grocery lists, and keeping track of kid food preferences and eating abilities. We can only assume that it’s folded into the physical labor. I found just one study, a 2013 survey of over 3,000 American adults over the age of 20 who had a spouse or partner, which asked about meal planning directly. These researchers found that 40% of women reported taking the main responsibility for meal planning and preparing, compared with just 6% of men. And women were much less likely than men to say they personally took no role in meal planning. This makes sense. It’s harder, and far less common, for women to opt out of meal planning because we are socially conditioned to do that task and held to higher societal expectations about what “good meal planning” looks like. I should note that 60% of women and 54% of men did say they viewed meal planning as a “shared job.” But the researchers didn’t clarify whether we’re all using the same definition of “shared job.” I suspect at least some of these men were giving themselves participation trophies for answering with a noun when their wife asked, “What do you want for dinner tonight?” Occasionally volunteering “pizza!” does not a meal planner make.

Meal planning offers a whitewashed vision of domestic life, sponsored by the Container Store, and inextricably linked to the thin ideal.

And women do all of this while navigating complicated cultural messages about how we and our children should eat and look. Meal planning means assuming responsibility for your family’s nutrition, and that almost always means some level of participation in diet culture. A search for #MealPlanning on Instagram brings up over 1.5 million posts, the vast majority of which are about dieting: meal plans that are dairy-free, grain-free, low-carb, raw, or keto. Meal plans with stringent calorie counts. Meal plans that make you start each day with a glass of warm lemon water. Meal plans that use egg whites in every meal. Meal plans that are just smoothie recipes because you’re apparently planning to stop chewing. I even found a meal plan based around “pickle bites” where you use pickles the way another person might use bread. This is all before we even get into #WhatIEatInADay TikTok, which is pretty much all before and after weight loss photos and diet rules.

So many of these posts come from women. Women getting their beach bodies or their pre-baby body back. Women sticking to their diet by packing salads to take to the office every day. Women planning to eat the rainbow and feed it to their family, too. Social media has convinced us of the utility of meal planning, and it has also taught us to crave the meal planning aesthetic — adorable printable calendars, fridges full of produce organized by color in clear acrylic bins. Meal planning offers a whitewashed vision of domestic life, sponsored by the Container Store, and inextricably linked to the thin ideal.

So yes, we do impact, and, in some sense, even create our children’s body image and their foundational relationship with food. And that power means we can cause harm: Studies show that mothers who model dieting or encourage weight loss are more likely to have kids who engage in binge eating and restriction. We also pass on our own internalized body ideas and weight biases to kids as early as preschool. But rather than staying stuck in shame or denial, we need to now reckon with all the expectations we’ve absorbed — and figure out how to begin the process of letting them go.

Excerpted from FAT TALK: Parenting in the Age of Diet Culture by Virginia Sole-Smith. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2023 by Virginia Sole-Smith. All rights reserved.

This article was originally published on