Policy

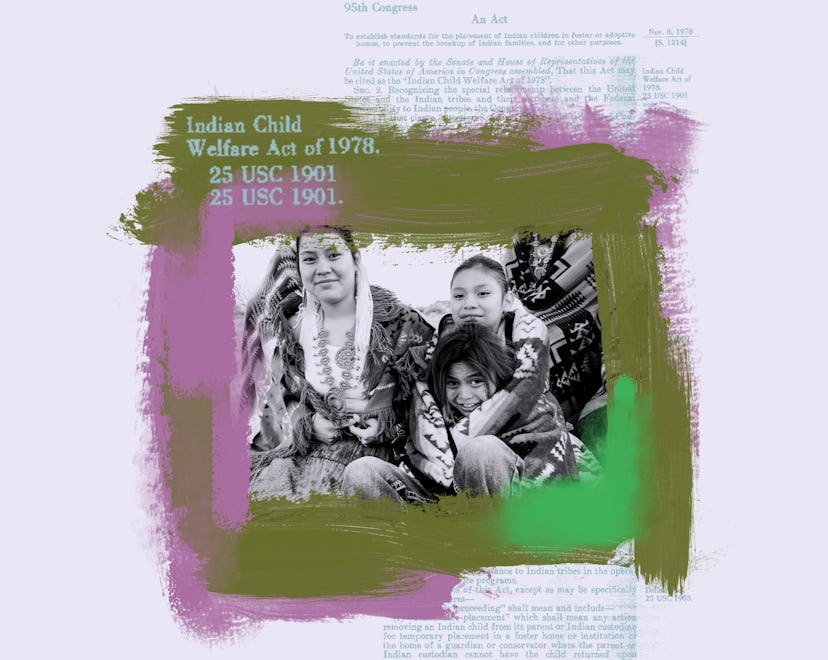

The Indian Child Welfare Act Saved A Generation Of Children. The Supreme Court Is Poised To Gut It.

Every Native child deserves the deep sense of safety that comes with being cared for in a home that shares their culture.

When Bríghid Pulskamp Lewis and her husband first learned about the young Navajo boy they would eventually take in, he had been misidentified as Hispanic and placed in a Spanish-speaking home. He had shut down and wouldn’t stop crying. Lewis quickly realized that he was a relative: the little boy was from the same clan as her grandpa. She asked to foster him, telling the social workers, “We’re related, he should be here with me.” When the boy arrived, he walked around the Lewis home in silence, until he noticed a picture from the Navajo reservation. “I know this place,” he said. It was a picture of the area where Lewis’ grandfather was from. The boy told her the road in the picture led to his home; Lewis told him that was where her grandpa lived, too. She told him he was her “little grandpa” and the boy's face lit up.

While the boy stayed with her family, they prepared traditional Navajo foods, looked at pictures of the Navajo reservation and talked about the animals there, and sometimes even spoke in Diné, their language. He stayed with Lewis and her family until his father could take care of him, an arrangement that was possible because of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), the landmark federal legislation that was designed to keep Native American families together and to help Native children retain their culture.

The ICWA prioritizes keeping Indigenous foster children and adoptees within their family, tribe, and culture, through a tiered system of adoption. Preference is given to family members or others from the same tribe; if a placement cannot be found through those two options, then another Native American family can be found. The last option is adoption with a non-Native family. “ICWA allows children to maintain their connection to their tribal nation,” says Beth Wright (Pueblo of Laguna), a staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund. “And that’s invaluable because Native children are the strength and the future of tribal nations.”

The ICWA was signed on Oct. 24, 1978, in response to the alarming numbers of children who were being stolen by public and private agents and placed in non-Native homes. At the time, 25% to 35% of all Native children were in adoptive homes or foster care. Today, the proportion of children removed from their homes is lower, but American Indian and Alaska Native children are still overrepresented in foster care.

Some Native people remember being told to hide if an unknown car pulled up to the house, and many Native communities have stories of young children being stolen and put up for adoption while adults were at work. Through the 1960s and ’70s, Native children were taken through a governmental program called the Indian Adoption Project. The Indian Adoption Project was an attempt to assimilate Native people by taking them out of their culture and placing them in non-Native households. It was an extension of the Native American boarding schools, which sought to assimilate Indigenous people through often brutal means. The Indian Adoption Project led to a steep loss of culture and identity for Native adoptees, which the scholar Carol Locust has called the Split Feather Syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by the grief experienced through the loss of heritage, language, spiritual beliefs, and tribal affiliation. These children grew up not knowing who they were and, once they reached adulthood, they faced disproportionally high rates of addiction, mental illness, and suicide.

Lewis, who is Navajo and who has worked with Native children and adults, and her husband were ICWA-certified, and for eight years they opened up their home to Native American foster youth, including the little boy from her grandfather’s clan. “ICWA can work its magic in a quick instance,” Lewis says.

The ICWA was a response to the alarming number of children who were being stolen by public and private agents and placed in non-Native homes. At the time, 25% to 35% of all Native children were in adoptive homes or foster care.

While ICWA is lauded by many as the gold standard in child welfare, it is currently under attack. A case challenging the law, Brackeen v. Haaland, has been taken to the Supreme Court and will be heard on Nov. 9. If the Supreme Court rules that ICWA is unconstitutional, it could have devastating effects on the lives of Native American children and families.

The Brackeens are a Texas family who claim God called them to foster and adopt children. In 2016, they fostered a baby boy of Cherokee and Navajo descent who they knew they would likely not be able to adopt because of ICWA. In 2017, when a Navajo family was interested in adopting the boy, the Brackeens decided they wanted to adopt the boy, arguing that taking him out of their home would traumatize him. With the help of pro-bono lawyers, money from conservative think tanks, and the Texas attorney general, the Brackeens took their case to court and were ultimately able to proceed with their adoption of the boy. Currently, they are also trying to adopt the boy’s biological half-sister, arguing that they are wealthier than the girl’s current guardian, a great-aunt who wishes to adopt her so she can grow up on the Navajo reservation within her family and culture.

The Brackeens argue that they have been discriminated against because they are non-Native. They further argue that ICWA violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states that a law cannot discriminate on the basis of race, gender, sexuality, etc. But for the plaintiffs, Brackeen v. Haaland is not about child welfare or even the constitutionality of the ICWA. Brackeen v. Haaland is an attempt to limit Native American rights and sovereignty. Critics of these efforts believe that for those working against ICWA, this is about gaining access to resources that tribes have.

For years, conservative forces have attacked the constitutionality of civil rights laws such as the ICWA. This Land, a podcast about Indigenous rights, uncovered a slew of connections between the Brackeens’ lawyer Mathew McGill and a group of conservatives fighting against Native American rights. Gibson Dunn, the firm where Mathew McGill works, represents some of the top casino and gaming companies, as well as the pipeline company involved in the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.

“This effort to attack ICWA and to find it unconstitutional based on equal protection grounds is actually at its core not anything about child welfare. It’s all about undoing the concept of citizenship and nationhood and tribal sovereignty,” says Kimberly Cluff, the legal director of California Tribal Families Coalition. “They’ve taken one of the key arguments in the Brackeen case and they’ve already made it in a case in Washington about gaming. Exact language.” If the Supreme Court decides that ICWA violates the Equal Protection Clause, then the precedent is set for questioning all of Indian law.

“ICWA is not race-based, it’s citizenship-based because the child has to be a citizen of their sovereign nation,” Cluff continues. The relationship between the U.S. government and Native Nations is considered nation to nation; and in that, it ensures Indigenous sovereignty. Through the agreement that Native Nations have with the U.S. government, tribal members are citizens of their respective tribes. “That’s where the threat to sovereignty comes from. They’re trying to undermine, either through direct argument or indirectly, the government-to-government relationship between the United States and tribes,” says Dan Lewerenz (Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska), an assistant professor of law at the University of North Dakota School of Law.

“If I can prevent a Native child from having to face disconnectedness and further harm, then that is what I am set on doing.”

When the ICWA is not applied, the effects can be devastating, as Native survivors of the foster care system can attest. I spoke to one such survivor, Marshal Galvan Jr., over Zoom. He. had spent most of his childhood in a series of foster homes. His story began when he was just 4 years old and cops rushed onto his family’s property. After placing him and his two sisters into police cars, the police arrested his parents and placed them in separate cars from Galvan and his sisters. At the police station, he saw his parents handcuffed like criminals. Galvan and his sisters were separated and placed into the foster care system.

There, Galvan endured physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. These traumatizing experiences led to addiction and incarceration in his early adulthood. Galvan, now in his early 30s, says the experience in foster care was much worse than his early life with his parents. He admits that yes, his parents had their problems and could be, at times, physically abusive; but the abuse he endured in foster care caused much of the harm that it was supposed to protect him from. At least if he had grown up with his parents, he would have learned about his Indigenous heritage and his culture’s traditions. “The harm that ensued after I became a dependency of the court was unspeakable,” says Galvan. “If I can prevent a Native child from having to face disconnectedness and further harm, then that is what I am set on doing.” It wasn’t until Galvan took sobriety seriously and he began to understand his Indigenous heritage that life started to make sense.

Galvan is now working through graduate school at UC Berkeley, where he studies child welfare and is an advocate for the Indian Child Welfare Act. “I am choosing to pay closer attention to ICWA policy because it was the very thing that my family was not afforded in the 1990s when we went through the child welfare system,” Galvan tells me. Because his tribe was federally recognized in 2019, he slipped through the system. He is now an enrolled member of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana. Galvan’s story is a warning about what generations of Indigenous people could again experience if ICWA is struck down: the violent erasure of their hard-won rights, for which Indigenous children will suffer most of all.

Support and learn more about ICWA:

Follow @protectICWA on Twitter and Instagram and sign the Protect ICWA petition

Listen to the This Land podcast, Season 2

Demelza Champagne is an Anishinaabe/Métis writer, enrolled in the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. She grew up in Los Angeles and has lived in many cities throughout the United States. She currently lives in Temecula, CA with two cats, her brother, and niece. She is working on her first novel and helps other writers to finish their novels.