Parenting

The Awful Night At The Hospital That Led To My Baby’s ‘Failure To Thrive’ Diagnosis

A pediatric nurse ignored my screaming baby, but something was definitely wrong.

It began when a nurse told me I was not allowed to breastfeed our daughter, for now; her breathing was so labored, she’d have aspirated the milk, leading to a lung infection. They inserted an IV into my 4-month-old baby to keep her hydrated, and each time my husband, David, came to relieve me, I would escape to the other side of the room with my breast pump, anxious to keep my supply up. In the pouch of my breast pump bag was a supply of apples and granola bars, all I had to sustain me during the long hours of the day when David was gone.

Not being able to nurse Sammi left me feeling useless. In the four months since her birth, she’d gained almost 7 pounds, all on my milk. I was proud of this, and what’s more, my growing feelings of guilt over not feeling as connected to her as I was to her older sister had been quieted daily by that intimacy. Her eagerness to nurse was my reassurance that she needed me. I’d relished the rush of oxytocin — the “love hormone” — that accompanied my milk letdown. Holding Sammi in my arms, feeling her body relax as she nursed, was the closest I’d come to communing with her. I didn’t know what was wrong with her breathing. I didn’t know why she barely slept. I didn’t know how to fix the ache I saw in her eyes, a plea for rescue I couldn’t fully grasp, but I could nurse her, and that was sometimes enough.

Now, I felt utterly defeated, holding her in my arms in the hospital room, helplessly refusing her the one thing she wanted most. As I rocked, bounced, held, and worried about her, I felt myself and my own needs floating away. I had to pee, to eat, and to sleep, but none of those things happened on my schedule anymore. I’d brought my GRE study book with me, thinking I’d practice logic problems for my upcoming exam while she slept, but there were few opportunities for that. In my all-encompassing worry, there wasn’t even time for my frustration.

I didn’t know why she barely slept. I didn’t know how to fix the ache I saw in her eyes, a plea for rescue I couldn’t fully grasp, but I could nurse her, and that was sometimes enough.

Mothers are like this, I learned. Mothers lose their selves.

A few hours after David left on our fourth night, Sammi began to cry with a new intensity. Without nursing in my tool kit, I tried singing, rocking, dancing, petting, whispering in her ear, and walking the room. Nothing worked. Nurses and families passing by her room looked curiously at us: a sweating, bedraggled mother and her screaming, frantic baby.

After an hour, I was sure something new was wrong. To the nurse who came to monitor her vital signs, I said, “I wonder if something is hurting her.”

The nurse brusquely looked in her ears again, checked her diaper, and told me not to worry. She shut the door behind her as I resumed my shuffle around the room, Sammi screaming into my shoulder.

My ears had begun to hurt from the volume of her cries, so I carefully maneuvered her into the sling again, trailing wires and cords. I wore a path between the bed and the crib, the chair and the wall. Several times, I collapsed into a wide-legged seated position, my 11-pound 4-month-old tight against my chest, and tried to determine whether her cries were louder or unchanged.

Desperately alone, I panicked, silently. By 10 o’clock at night, nearly two hours into this unbroken misery, the nurse told me again that there was nothing wrong with Sammi. I burst into tears.

Her face softened slightly, and she put her hand authoritatively on my shoulder. “Come on, Mom,” she said firmly. I remembered later that my name was not Mom, that I was not her mom. “You have another child. You know babies cry sometimes, and we don’t always know why.”

“But this isn’t like her,” I pleaded. “This is a different cry. I don’t know how to help her.”

“I have an idea,” the nurse said, peering up at the television. “Have you ever tried one of those Baby Einstein videos?”

Momentarily, I was too angry to be distraught. The insanity of this suggestion — that a 4-month-old baby would shriek like this due to boredom — left me speechless. Still, I let her try. In a series of surreal moments, I pointed at the screen and narrated for Sammi. It’s a bear! Look at the bear!

She cried on, never opening her eyes. Soaked against my chest in the sling, she seemed utterly unaware of anything outside the tiny universe of whatever she was feeling. We paced the room to the tune of the xylophone music on the screen for another 10 minutes, after which I turned it off and finally contributed a soundtrack of my own sobs, moaning, “I’m sorry I can’t help you. I’m sorry you’re so sad. I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.”

The nurse closed the door to the hallway, which she’d accidentally left open, complaining that we were keeping the other patients from sleeping.

At midnight, a new nurse came on shift. She came into our room where I was pacing with Sammi, who was still wrapped in a sling on my chest, crying and clutching my shirt in her free hand. I had one hand on the IV pole and another patting her bottom. My lips were pressed against the top of her ear, no longer shushing or singing, only murmuring nonsense, utterly shattered. The new nurse took one look at us, closed the door gently behind her, sat in the chair by the side of the bed, and said, “I hear you’ve been having a rough night.”

“Yes,” I said, out of tears and over the sound of Sammi’s continued cries, which by now were getting softer as she lost her voice. “I don’t know what to do. She’s never been like this before, not ever.”

“Well,” the nurse said, never taking her eyes off us, “you know, she’s been on IV fluids for days now, so she’s hydrated and getting some nutrition through that, but her tummy still might feel empty. We might be able to try giving her a bottle. Do you have any expressed breastmilk?”

“Yes!” I said. “Yes, it’s in the fridge down the hall. It’s labeled with her name.”

“Why don’t you let me hold her while you get some? I can give her a bottle; maybe she’d be more likely to take it from me.”

Can no one effectively feed this baby? I thought.

I eased Sammi out of the sling, careful to hold the IV tubing and monitor leads away, and placed her, still howling, into the arms of the nurse. Before I could reach the door of the room, the nurse said from behind me, “Wait. When was her IV last checked?”

“I don’t know,” I said, turning to face her. “Don’t they do that when they check her vitals?”

The nurse was removing the splint around Sammi’s IV as I answered, and she interrupted. “Go to the nursing station right now and bring me two more nurses. Tell them we have an infiltration.”

“What is that?” I asked.

“They’ll know. Just go right away,” she answered, laying Sammi on the bed. With the empty sling still dangling from my neck, I did as she asked, and when the nurses I found heard why they were needed, they leaped up and ran to our room.

What was happening was indeed alarming. Sammi’s IV needle had infiltrated the tissue of her arm.

Intravenous infiltration occurs when the needle bringing fluids into a patient’s vein comes out of the vein and into the surrounding tissue. Instead of the fluid from the IV bag entering the patient’s bloodstream, it enters the area under the skin, spreading further and further as long as fluid continues to flow through the needle. It can happen the moment an IV is inserted, or it can happen afterward due to a change in position or extra-tight tape or just bad luck.

Sammi’s IV probably had infiltrated sometime around 8:30 p.m. The nursing shift change happened at midnight, so Sammi likely had IV fluid — in her case, a combination of saline and dextrose — entering the tissues of her arm the whole time. When the nurse removed the splint around her IV, Sammi’s hand and arm were swollen with fluid from the tips of her fingers almost all the way to her armpit. Her hand was so swollen that her fingers were stuck together. The skin of her wrist had begun to split. When the new nurse removed the IV and applied a warm compress, Sammi stopped crying almost instantly, looked up at me, and smiled. Moments later, she fell asleep in my arms. I watched in horror as yellow droplets of IV fluid began bubbling up through the skin of her arm.

I had no idea, then, that what had happened was the result of negligence. I put the bottle of pumped breastmilk on the bedside table, forgetting I’d even brought it from the refrigerator until the next morning when I found it curdled there. I couldn’t focus. I was soaked in sweat — as was Sammi — and so wrecked from more than three hours of begging for someone to take me seriously that the only thing I could do was climb into the hospital bed, tuck Sammi into the crook of my arm, and fall into a heavy sleep.

In the morning, the nurses told me they had stopped by every hour all night long to shine a flashlight in Sammi’s eyes, take her temperature, and replace the warm packs on her arm. We had both slept through it all.

My husband can’t hear or read this story without turning away or tearing up.

That next day, a resident admitted to me that in medical school, when he and a friend were practicing IV insertion on each other, his friend asked him to deliberately insert the IV in the tissue instead of in the vein, just to see how infiltration felt. This resident’s friend described it as extremely uncomfortable — that he could feel his skin tightening and filling with the saline solution in the IV bag, and he removed the IV in under a minute. That was enough time for him to know that infiltration was unbearable.

Sammi’s IV had been infiltrating her skin for four hours.

No new IV was inserted during the remainder of that hospital stay. Instead, slow-flow nipples were fitted to the bottles of breastmilk I’d pumped, and she drank my milk again. Though she crooked her neck hard against my chest, trying to nurse instead of bottle-feed, eventually her hunger got the best of her, and she managed the bottles, barely. It was not lost on me that my inability to breastfeed her as I’d wanted was what led the nurse to hold her and discover the problem.

Can no one effectively feed this baby? I thought.

I would have that answer, in time. It was no, until it was, finally, yes. It would take nine years, during which I would realize, too, that the story seldom contained my own feeding, either. All those hours in the local pediatric ward, all the hours in the children’s hospital, in my kitchen, in my car, sipping hot chocolate while Sammi slept in the back seat. We get fed, but we don’t always get nourished. We get care but not cared-for.

My husband can’t hear or read this story without turning away or tearing up. I can, between sips, tell it to you with dry eyes. Mothers lose themselves. They lose their names. They lose their needs. All this, but they keep their stories.

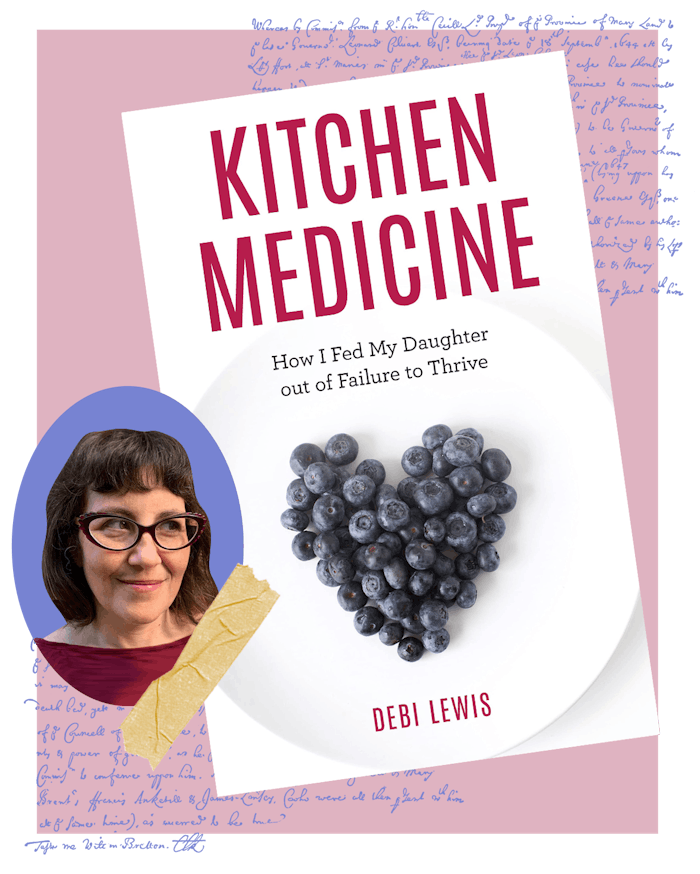

Debi Lewis’ memoir, Kitchen Medicine: How I Fed My Daughter out of Failure To Thrive is available now.

This article was originally published on