Op-Ed

The Law That Protected My Daughter's Connection To Her Culture Is Under Threat

She can thrive with her adopted family because of her deep connection to one she was born into.

I do not know to whom my daughter, Sage*, gave the gift of her first laugh. This certainly isn't because she didn’t laugh as a baby — her big brother could get her giggling so hard that she would snort with delight. She likely gave this gift to her brother, or maybe even to me, but I didn’t mark it in my mind because I didn’t yet know its cultural significance.

In Navajo (Diné) tradition, a First Laugh Ceremony (A’wee Chi’deedloh) is organized by whomever inspires a baby’s first giggle, and hosted by the baby herself. That first laugh marks a transition from the spirit world into life with her family. She can receive and wear her first turquoise, and she gives gifts of food and rock salt to symbolize continued connection to the earth, generosity, and joy.

Missing this ceremony was not our first adoptive-parent blunder as a non-Native, east coast family — nor would it be our last. We knew that cross-cultural adoption would be challenging, so we had hoped to connect right away, even before her birth, with Sage’s family and people who share her heritage. Research indicates that strong and resilient identities in adopted children come from connection to their families and cultures and lead to many positive outcomes, like improved mental and emotional health. Our wish was for an open adoption, which the science about well being strongly supports.

The adoption agency and legal counsel, however, pushed us toward a relatively closed adoption process. Attorneys ignored our requests for more information about Sage's Tribal connections. It felt like speeding up the process was more important to them than doing what was in the best interests of the child. We had a particularly difficult time getting answers to our questions about a federal law called the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA).

She is loved dearly, but as an adoptee, Sage lost the opportunity to deeply know the person whose heartbeat kept rhythm over her first nine months of life.

The ICWA serves as a crucial tool for openness in adoptions because, when properly followed, it informs “Indian children” of their identity and heritage. (Note: “Indian child” is the official, legal term used to describe a child who is a member of, or eligible for, enrollment in a federally recognized tribe and has a biological parent who is a tribal member.) The ICWA governs the process of adoptions to try to place children in the best possible home. When an Indian child enters foster care or is up for adoption, the ICWA prioritizes placement with the child’s relatives, but some children do not have relatives to take them in. In that case, welfare workers try to find a placement for the child with a member of their Tribe, or another Native family. If such placements are unavailable, or if a judge finds “good cause” to diverge from the placement preferences, then non-Native families, like ours, have the opportunity to adopt the child.

When we were “matched” with Sage’s birth mother in 2020, however, all we were told about the ICWA was contained in a short note at the bottom of an “estimated adoption costs” email. It merely mentioned that, due to suspected Native heritage, the process would involve ICWA, take longer, and require hiring an additional lawyer.

Frustrated with our attorneys, who advised against communicating with the Tribe, we contacted the Navajo Nation ourselves. Once Sage was home with our family, but before she was 6 months old (when official adoption proceedings were expected to begin), we shared our story, as well as our hope that Sage be given the chance to connect with her Tribal heritage. We were relieved to hear that the Navajo Nation would try to help us in our learning and legal processes. But tribal involvement from the outset, as the ICWA encourages, could have meant that we were put in touch with a cultural mentor or family member much earlier. Perhaps in time for us to plan Sage’s First Laugh ceremony.

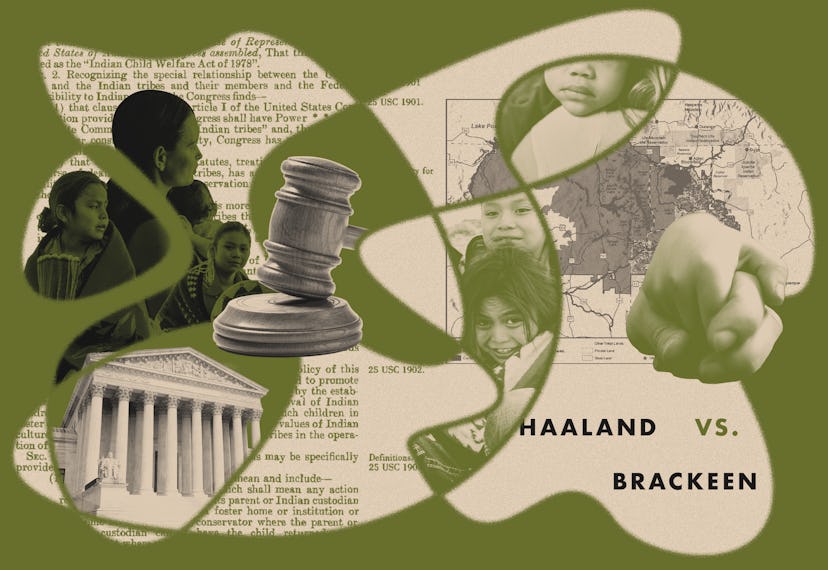

Right now, certain players seek to overturn the ICWA. In the case of Haaland v. Brackeen, the Supreme Court will decide whether to throw out the few remaining protections connecting Native adopted children to their Tribes and extended families. The ICWA opponents have two things in common: deep pockets and minimal contact with Native tribes, organizations, leaders, or peoples. They say they want the best for Native children, but, per the National Indian Child Welfare Association, “not a single Tribal Nation, not a single independent Native organization, and not a single independent child welfare organization” supports their cause.

On the other hand, 497 Tribal Nations, 62 Native organizations, 23 states and Washington, DC, 87 congresspeople, 27 child welfare and adoption organizations, and many others, have signed on to 21 briefs submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of upholding the ICWA.

She almost lost the opportunity to weave herself into the stories, spirituality, and cultural rhythms of her ancestors.

The ICWA provides a vital connection between a Native child and her Tribe, so that even if a non-Native family like ours raises a child like Sage, she has an easier path through which to know her heritage, genealogy, medical history, and customs. Thankfully, because of the ICWA, at a minimum our lawyers were required to mention our daughter’s “potential Native heritage.” So, while their description of the ICWA and its implications was clearly inadequate, at least it led us to start asking questions. If this law is overturned, more adoptions will be shrouded in secrecy, which hurts children, birth parents, and adoptive parents.

As our story demonstrates, the ICWA doesn’t prevent “non-Indians” from adopting children, as opponents of the ICWA and plaintiffs in the lawsuit have claimed. It just tries to ensure that children can thrive, because developing a positive sense of identity is critical to a child's health and happiness.

We are so lucky to have the privilege of raising and caring for Sage. She is loved dearly, but as an adoptee, Sage lost the opportunity to deeply know the person whose heartbeat kept rhythm over her first nine months of life. Then, because our attorneys were skirting the ICWA, she almost lost the opportunity to weave herself into the stories, spirituality, and cultural rhythms of her ancestors.

Our family has been hurt, not by the ICWA, but by those who seek to subvert it. I urge everyone to protect Native adopted children from that second loss — the loss of identity and culture — by signing this petition and supporting the ICWA. With a decision in Haaland v. Brackeen expected to come imminently, it’s up to us to bring attention to this issue in the court of public opinion.

For more information about the ICWA and the Haaland v. Brackeen Supreme Court case, please check out Season 2 of This Land (a podcast from Crooked Media).

*Sage is a pseudonym used to protect the identity of a minor.

Aubrey Nelson is the adoptive mother of a Navajo child. She works as an educator and lives with her husband and their two children in New England, the traditional homelands (N’Dakinna) of the Abenaki peoples.