Parenting

The Joy Of Learning Cree Through Children’s Books

My grandmother’s first language was nêhiyawêwin, but I never heard her speak it. Now my young daughter and I are learning it together.

Like most 2-year-olds, my daughter loves books. Nearly every day ends with a pile of them on the couch, as she runs back and forth to the bookshelf to get “just one more story.”

When I was pregnant with her, the only gifts I asked for were books. This wasn’t as high-minded as it sounds: I was overwhelmed by the prospect of making a registry, and I was worried people would buy me ugly baby items and I would have to pretend to like them. But I’d been raised to believe there was no such thing as too many books, and I loved the idea of my daughter starting her life with a library of her own.

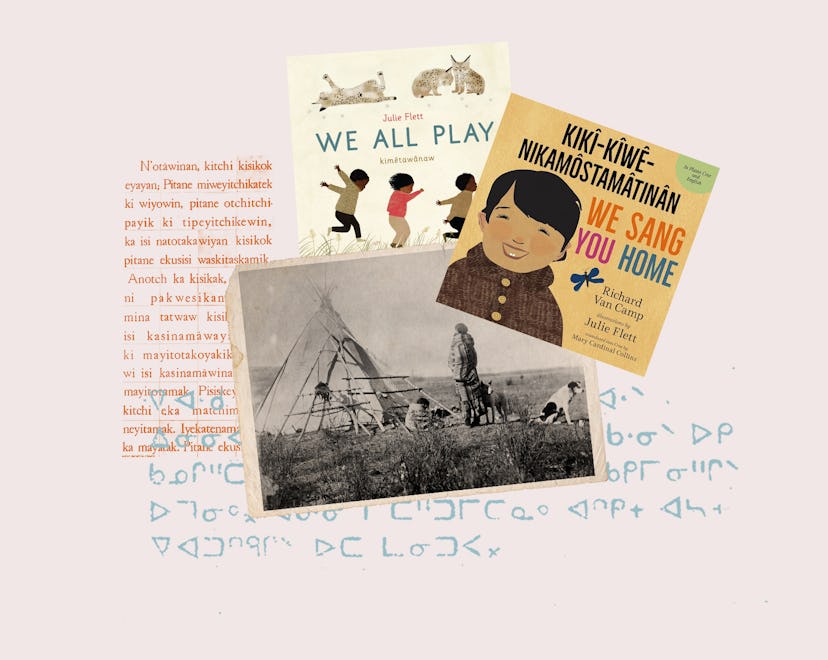

By the time she arrived, we had a full bookshelf. Many of the titles were familiar — Goodnight Moon, Where the Wild Things Are, the reliably devastating Love You Forever. But I was touched to see that so many of our friends and family had given us books by Indigenous authors and illustrators: Roy Henry Vickers, Katherena Vermette, Richard Van Camp, Michael Kusugak. Best of all were the books about my people, nehiyawak. Many feature the stunning illustrations of Cree-Métis author Julie Flett, are written bilingually in Cree (nêhiyawêwin) and English, or feature nêhiyawêwin words throughout.

When we read them, my daughter and I learn together, sounding out new words: atim, dog. Misatim, horse — literally “big dog.” The Inuktitut word for horse also translates as big dog, and I love imagining various Indigenous peoples seeing a horse for the first time and thinking, “Huh, that looks like a dog but bigger.” Toddlers think this is very funny too, which is another reason why it’s fun to learn nêhiyawêwin with them.

Speaking an Indigenous language is an embodied act of hopefulness: Each word is a link to the past.

My grandmother’s first language was nêhiyawêwin, but I never heard her speak it. Like most Indigenous people of her generation, she attended a residential school, where she was forbidden to speak anything but English. And like many people of my generation, I grew up in an urban area, far from my nation. I didn’t know any nehiyaw people besides my own family, and I often felt vaguely fraudulent: How could I be Indigenous when I didn’t look or act like any of the Indigenous people I found in books and movies?

It didn’t help that the only Indigenous characters I encountered were written by white people: Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O’Dell; Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech; and, of course, The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks. These authors drew on stereotypes and fantasies of Indigenous people as savage, mystical, animalistic, simple. Salamanca, the protagonist of Walk Two Moons, thinks to herself, “My mother and I liked this Indian-ness in our background. She said this exotic substance in our blood made us appreciate the gifts of nature; it made us closer to the land.”

In 2022, this reads as pure cringe, but if you are an Indigenous millennial, it was the best representation you could hope to find in the media of the ’80s and ’90s. The alternative was The Indian in the Cupboard, with its tiny, bloodthirsty warrior who is gradually tamed by a benevolent white boy. Since it was published in 1980, The Indian in the Cupboard has sold almost 6 million copies, making it by far the most widely read depiction of an Indigenous character ever, which is so awful I can’t even think about it.

When I look at the gorgeous, imaginative books on my daughter’s shelf, it depresses me to think of someone buying them joylessly, for the primary purpose of ensuring their white child doesn’t grow up to be prejudiced.

Things have improved since then: After a long plateau, books featuring nonwhite characters began increasing slowly but steadily from 2014 on. In 2021, 2% of books featured Indigenous characters, and while that number could be higher, at least those characters are more likely to be written by Indigenous authors. But outside the home, there are still hurdles for getting those books into the hands of children. Across the United States, parent groups are protesting the inclusion of diverse books in school libraries that might upset white kids. In Canada, an Ontario school district removed a young adult book by acclaimed Cree author David A. Robertson from its libraries, citing “too much culture and ceremony.”

Those protests are fortunately met by parents and organizations who fight for the inclusion of these stories, even ones that grapple with important topics that some children might find upsetting, like residential school or slavery. I’m thrilled for the families who get to see themselves reflected authentically in the stories they read with their children, and I think it’s a valuable goal to provide all children with books that enrich their understanding of the world. But when I look at the gorgeous, imaginative books on my daughter’s shelf, it depresses me to think of someone buying them joylessly, for the primary purpose of ensuring their white child doesn’t grow up to be prejudiced.

Because, for me, and for many, it’s pure pleasure to read a book like Kimêtawânaw with your child, to pore over the illustrations, to pronounce a language that has been spoken on these lands for thousands of years. It’s beautiful to discover that the word for moon in nêhiyawêwin, tipiski-pîsim, translates to “nighttime sun.” I don’t want people to think of any Indigenous book as an interchangeable diversity lesson for their non-Indigenous kids; I want them to revel in the celebration and specificity of the language, culture, and stories.

Nêhiyawêwin is actually composed of five main dialects; my ancestors spoke Plains Cree, also called the “y” dialect. When the five dialects are counted together, it has the most speakers of any Indigenous language in Canada, with almost 100,000 speakers. As a result, there are a ton of learning resources: books, online dictionaries, YouTube channels, podcasts. If I’m curious about a word, I can look it up; if I don’t know how to pronounce something I read in a picture book, I can often find a YouTube video or recording to help me. In some places, children can learn it in schools. This is an incredible gift, especially when I think about all the Indigenous languages that were extinguished by colonialism and have no living speakers left.

I take notes from my daughter, who is curious and open, who knows she has her whole life to learn what she doesn’t know yet.

Reading with my daughter helped me unlearn the shame of not knowing the language. For most of my life, I was embarrassed about this, as if it were my personal failing and the inevitable result of generations of forced assimilation efforts by the government. Now I’m gentler with myself. I practice the words I know; I look them up when I forget. I take notes from my daughter, who is curious and open, who knows she has her whole life to learn what she doesn’t know yet. It makes me think of a line from one of our favorite books, We Sang You Home (Ka Kîweh Nikamôstamâtinân) by Dene author Richard Van Camp and Cree-Métis illustrator Julie Flett: “Through you we are born again.” mwecih âsa mîna kâwih nihtâwikîyan.

Sometimes I think about how it’s common for people to prepare for travel by learning a few words or phrases in the local language. This habit is useful but also respectful, a way of acknowledging that you’re a visitor who is trying their best. And yet people seldom take the same care in North America with Indigenous languages. It’s intimidating, I know: A language like nêhiyawêwin is much harder for English speakers than a related language like Spanish or French. nêhiyawêwin is often written in syllabics, which adds another layer of unfamiliarity for English speakers. That’s partly why for years I didn’t try to learn at all; it seemed impossible that I would ever grasp it. But when I read with my kid, the words feel within reach. We’re learning them together, one at a time.

Speaking an Indigenous language is an embodied act of hopefulness: Each word is a link to the past. Learning them is the only way to carry them forward into the future, to ensure their survival. There’s no direct translation of the word goodbye in nêhiyawêwin; instead, you can say ka-wâpamitonaw âsay mîna — “We’ll see each other again.” I think of it whenever we finish a book, and put it back on the shelf until next time.

Michelle is a writer, editor, and magazine publisher. Her words have appeared in the Vancouver Sun, SAD Mag, Chatelaine, Vancouver Magazine, MONTECRISTO, and other publications. She lives with her husband, daughter, and weird cat in Vancouver, Canada.

This article was originally published on