Doomscroll This

Why We Can’t Look Away From Momfluencers

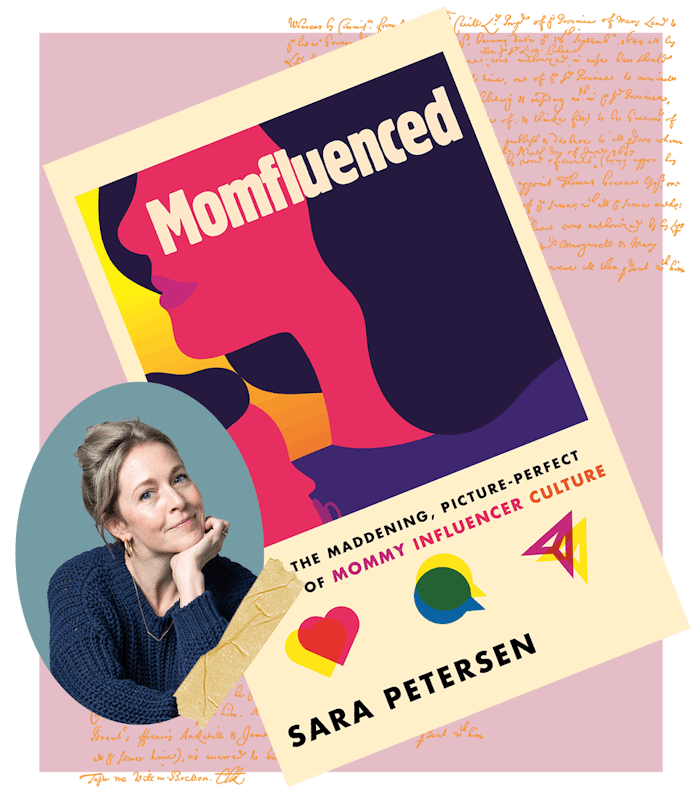

Sara Petersen’s Momfluenced is a deep dive into the billion-dollar slice of influencer marketing that revolves around mothers and occupies an even bigger place in the zeitgeist.

I first stumbled across Sara Petersen and her delightful, slightly spun-out penchant for mom-centric cultural critique a few years ago on Twitter. Smart and always self-effacing, her relentless interrogation of the culture of motherhood — particularly on social media — always begins with self-critique. I was drawn immediately to her voice — which is often funny, long-winded, and a little profane — as much as to her ideas, which walk a juicy line between pop culture and academic critique. Her new book, Momfluenced, is a deep dive into the billion-dollar slice of influencer marketing that revolves around mothers (and often particularly aimed at new mothers) and comes out April 25. If you’re a mom on social media, this book deserves your attention. We got into the nitty gritty of why “momfluencers” occupy such a fraught place in the zeitgeist, and why — even if we know that we’re being used — we can’t stop scrolling.

I am so excited about all of your ideas and I think this is such an urgent conversation. I’ll jump in with maybe my least-graceful question: Do you think mom influencers are bad?

Um, no. No. I think the ideals undergirding what we expect from momfluencers are bad. I do not think momfluencers are bad.

You’ve gone so deep with this topic. What was your initial entry point?

[My first child] was born in 2012. My sister actually basically forced me to get my first smartphone when I was pregnant with him. ‘Cause she was like, you're gonna want better photos of your baby and blah, blah, blah. I still had a flip phone. I got my first smartphone in 2012 and I didn't create an Instagram account until my first was like 1 or 2, and I didn’t even know what blogs were until like, 2014. So it wasn't until my second kid was born in 2014 that I discovered this world.

When did you first start viewing it all from a critical perspective, shifting from a consumer of the content to an interrogation of exactly what’s going on with momfluencers?

Probably Hannah Neeleman from Ballerina Farm. With people like Naomi Davis and Amber Fillerup Clark, I had certainly had the thought that what they’re performing online is not representative of most mothers’ lived experiences. But with Hannah from Ballerina Farm, I think because her performance of motherhood is so deeply rooted in some of the more explicitly harmful and maybe quietly insidious ideals of motherhood that exist in the U.S., I started to really unpack [momfluencers]. It’s pretty obvious and glaring with her account, you can see traces of self-sacrificial motherhood, highly femme motherhood, heteronormative motherhood, white motherhood, class-specific motherhood. You can see those seeds in so many of the most successful momfluencer accounts. Her Instagram blew open the door in a really dramatic way for me.

Yes. I think about her account in contrast to someone like a Kardashian, where, like, there is no question that these people are bananas-wealthy. Right? They're not hiding that fact at all. They’re like, look at my Bentley! I’m so rich! And then Hannah, she is very quiet about her wealth. Instead, her posts telegraph something like Here’s my humble farm life and it’s so great, and yours could be like mine, but she doesn’t acknowledge that she looks so happy and she’s not stressed out because she has bottomless resources. That's not part of her brand.

Not at all. Hannah from Ballerina Farm is so complex, because she presents a down-to-earth, humble, conspicuously not-fancy lifestyle, despite the fact that she has a $20,000 stove, and despite the fact that to have bare boards in that kitchen, they had to do an expensive remodel. We’re just so trained to see like loud, flashy representations of conspicuous consumption as the model of it.

But with her and others like her, there’s still enormous privilege and enormous wealth making her lifestyle aesthetically distinguishable from the Kardashian aesthetic and supporting her narrative as like a “good mom” in really interesting ways.

Yes. In your critiques of momfluencer culture, have you ever shared thoughts about people working in that space that you’ve regretted, or gotten feedback from people that they felt your critiques were unkind? How do you feel about that?

I am such a people pleaser, and like just an insecure, quivering rabbit at heart. So, yeah. Anytime that I perceive that I’ve hurt someone's feelings, I shame-spiral and it’s really, really bad. I've gotten a couple comments about my critiques of Hannah from Ballerina Farm to the effect of like, “She’s not hurting anyone, she's just living her life.” That's where I do want to push back a little. Sure, she is not explicitly aiming to harm anyone, I don't think. But, the effect of her content can cause harm, whether or not it’s deliberate harm. Whether or not it's explicit or implicit, it is solidifying our understanding of a good mother as being white, thin, married, wealthy, happy, joyful, never complaining. It is supporting that ideal, whether or not she wants it to. I do think we need to be critical of that, and we do need to be critical of the narratives that we welcome about motherhood and the images that we praise about motherhood.

I try so hard to not level my cultural criticism at individuals, but rather the systems and the power structures that enable certain individuals to get a lot of air time in other individuals, not to get a lot of airtime, you know?

In the book, you talk with so much nuance about the ‘shopability’ of momfluencer accounts. I'm curious if — now that you went so deep into this world of influencer marketing, now that you know better — do you still swipe up? Or are you inoculated?

I don’t think I'll ever be safe. I don't think anyone who has Instagram will ever be fully inoculated. I just don’t think that’s possible. I’m probably less likely to consciously connect my purchases with a potentially more gratifying experience of motherhood. I say “consciously” because I truly don’t know what’s going on in my subconscious. I'm still transfixed by certain ads. Like Oak Essentials, which is the skin care and makeup line owned by Jenni Kayne. They have this ad for this balm and I’ve watched this f*cking ad so many times, it’s taking so much space in my brain. I have not bought it. It’s like $85, and I'm not convinced it’s drastically different from Aquaphor, but the potential for stuff we see on social media to suck us in, narratively, never ceases to amaze me. That’s why I don't think anyone is safe from it. I've read a sh*tload of stuff about marketing and performative femininity, and I am not even close to immune.

This leads into my next question, actually. For the most part, your critique of momfluencer culture is focused on content creators. But, since reading your book, I’ve been thinking about how momfluencers and their followers are all beholden to Meta or TikTok or whatever social media platform we’re using to interact. Ultimately, they have the power, right? If Meta changes the algorithm, as they do relatively often, women who make money as momfluencers can get really screwed.

I often think that, with Meta and all the tech companies that own these platforms, I sort of liken it all to an MLM [multi-level marketing] scheme, where they’re at the top and even mom influencers with like 200,000 followers can be working nonstop and maybe making $20,000 a year. Executives at Meta could just be working like a 9-to-5 and making like, eight times what the momfluencers are busting their a**es to make. And yeah, I think it's almost impossible for momfluencers to succeed, financially, without blurring their private and public lives in what can be really psychologically harmful ways.

The momfluencers are beholden to the app, and the constantly changing algorithms, and they’re also beholden to what that app’s community guidelines deem acceptable or appropriate concerning motherhood and femininity. People will say [things like] it’s great that they can be paid for the unpaid labor of motherhood, but they're not being paid for that. Nobody's paying them to console their kid who was bullied that day at school. They're paying for their ability to adhere to ideals of motherhood that are often steeped in whiteness and heteronormativity. It feels like a really confounding, impossible spot to be in for the momfluencers. Obviously it sucks for the rest of us in different ways, but yeah, I do think both sides of the coin are being exploited.

Related to that — do you come away from all of this thinking that we should all just delete social media?

If you have a specific issue that you're dealing with that you need community or resources for that you're not finding in your real-life community, then I think social media can be really empowering and helpful. That said, I don't see much of an argument for just the mindless scroll. If my work were not somewhat contingent on my social media presence, I would delete it from my phone. Every time I take a social media break and delete it for like a week or even two weeks, I just feel dramatic differences in my well-being.

Yeah. I think Instagram, when my first son was born, became this way of like, blasting out like an SOS to whoever was scrolling, and it was easier and less intrusive than directly texting friends. It was a way of accessing a broader network, and in a way, it helped me. Now with kids that are older, it just seems like pure distraction without benefit. When I have Instagram on my phone, it’s in my mind, like, is my kid doing something cute? I’ll take pictures in case they do something I should share. And then I’m not in the moment with him. It's an insidious mindset, and momfluencers’ incomes are dependent on living like this.

Well, and it stays with you. Even if I just scroll from like, 7-7:30 a.m., and don't look at it for the rest of the day, what I consumed in those 30 minutes, I can’t unsee, for better or for worse. The addictive nature of it, too — even if I don't look at it for the rest of the day, I will experience those little blips in my day when I'm bored or restless or whatever, where I'll be like, ooh, should I open it? Even just that, ooh, should I open it? That is taking up space. It’s like psychic noise. You know?

But I'm sure that to sell your book, you had to get your newsletter going, and be on social media. One could say you’ve had to become a momfluencer yourself, in a way, to influence people to buy your book.

Yeah. I feel super, super conflicted. I have meaningful interactions with people on social media that I am grateful for, but am I happier without it in my life? Yes. There's just no doubt in my mind. Because everything feels less noisy and less frenetic within me when I'm off it. For me, I know my healthiest practice for myself is going in, posting what I need to post, promoting what I want to promote and getting out, and responding to comments 24 hours later. It’s the consumption, for me, that is the entryway to the portal of doom.

You’re introducing so many external voices into your body and surrounding spaces, and you don't know what those voices are going to say. It’s just so risky and fraught every time.

What it triggers in me is judgment. I really hate who I become as I look at my friends’ pictures. That voice in my head that sees friends’ photos and goes well, I would never do that.

I try to always say that with my critiques of certain content creators, it’s never about them. It's always about me: what I am struggling with, what I’m missing from my own life, what I’m insecure about. It’s not a bad thing to have an awareness of how much consumption is conscious and versus like, what is what's going on in the subconscious. To consider how we could better know ourselves if this tool did not exist. Like, people have been trying to understand and know themselves ever since there were people.

I think it is robbing us of something essentially human in terms of self-discovery.

You can order Sara Petersen’s Momfluenced on Bookshop and wherever books are sold!