Small Packages

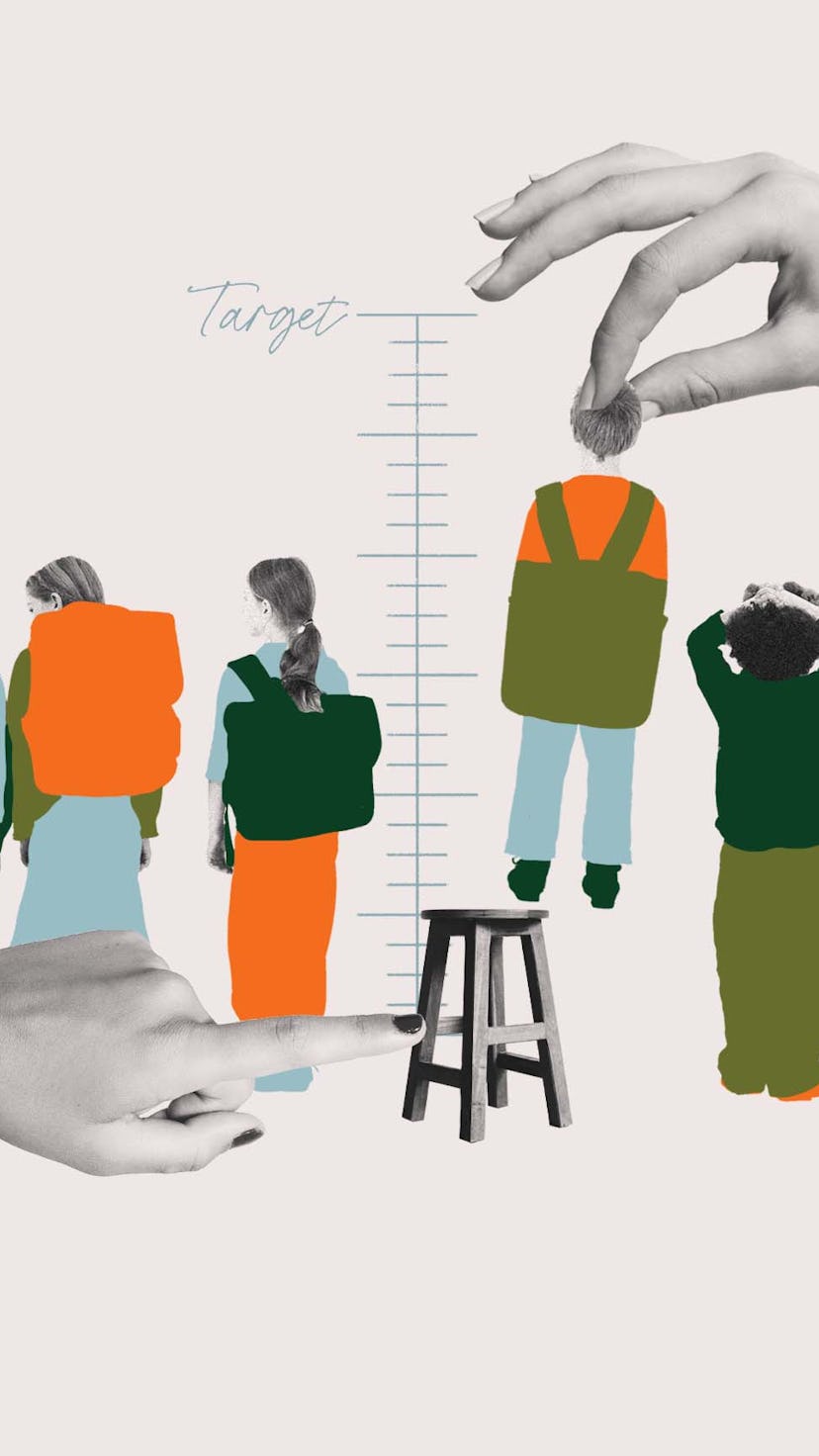

What Happens When The Doctor Says Your Kid Is Too Short?

When your child is super small, deciding what to do — or whether to do anything at all — is complicated.

I weighed only 5.5 pounds when I was born — full-term but tiny. According to family lore, after I'd been checked out and found to be healthy, the obstetrician quipped, "She's small, but she's a keeper.”

Every year that followed, I was the smallest kid in my class, always in the front row in team pictures, always struggling to find clothes that fit my age in years. I was consistently in the low single digits on the growth chart. By about 16, I'd crept up to my full adult height — a hair over 5 feet, just like my mother, and her mother too.

When my older daughter was born 13 years ago, she was also alarmingly small — a few ounces shy of 5 pounds. (Low birth weight is technically defined as anything under 5 pounds, 8 ounces.) In the moments after her arrival, doctors also quickly whisked her away, but soon returned and said that while she was a lightweight, she was healthy and strong.

Sometimes it felt like the only thing anyone noticed about me was how small I was.

As she's gotten older, she's barely skimmed the very bottom of the growth charts for height and weight. And like me, she has smiled from the front row of class pictures, struggled to find clothes that suit her age, and found herself shut out of all the “good” rides at amusement parks. She has endured classmates picking her up over and over and even using the top of her head as an armrest (yes, this actually happens). Classmates ask her if she can reach things at the very top of the lockers or question if she’s really the age she claims to be. None of this is fun, but I figured that by adulthood, she’d wind up like me: a little on the shorter side, no big deal.

At her 12-year-old checkup, however, her pediatrician announced that it was time to see an endocrinologist. The doctor noted that according to my daughter’s current growth curve, she was not on track to reach my adult height of 5 feet. The official height cutoff for “short stature” is below 4 feet 11 inches for post-pubertal girls and 5 feet 4 inches for post-pubertal boys, according to the FDA. (I can’t help but point out here that, according to the definition above, I am not even officially short?!) Given these definitions, and the fact that her father is nearly 6 feet tall, the doctor wanted to see if there was an underlying issue that needed to be addressed.

Despite the flicker of fear that happens whenever a doctor suggests seeing a specialist, I wondered exactly what an endocrinologist would be looking for. If my daughter doesn't seem to have any disease or deficiency, what can be done for the very petite? And more confusingly, if there are no medical issues, should anything be done at all? How much does it matter that my kid is increasingly and significantly upset about all of this—at feeling so different than her peers, and at the constant jibes coming her way as her age creeps up, her friends shoot up, and her height remains as slow and low as ever? I have to consider the short- and long-term psychological effects of being short, even if the answer is some variation of “grin and bear it,” or of “this too shall pass.” Off to the endocrinologist we go.

What can a pediatric endocrinologist do for short kids?

First and foremost, pediatric endocrinologists want to rule out diseases that can cause small stature. “These include endocrine diseases such as diabetes; underactive thyroid; growth hormone deficiency (a lack of a hormone secreted by the pituitary gland in the brain that drives childhood growth); genetic conditions such as Turner or Noonan Syndrome; skeletal abnormalities such as achondroplasia (the most common form of dwarfism); malabsorption or malnutrition,” says Dr. Michelle Klein, a pediatric endocrinologist in a private practice affiliated with Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City.

To start digging into whether those conditions are present, a pediatric endocrinologist will typically order blood and stool tests, a bone-age scan (an X-ray of the hand that can reveal if a late growth spurt is in store), and do a careful evaluation of family history. To check how well a child’s body is creating human growth hormone, doctors may also suggest a growth hormone stimulation test, a multi-hour, in-office test where blood is drawn several times while medicine to stimulate the pituitary gland to release growth hormone is also given via IV. (If that didn’t sound unpleasant enough, some children may also feel nauseous during the test.)

For kids whose tests don’t reveal any disease, abnormality, or something that could even be addressed through dietary changes, the cause may be either “familial short stature” or “constitutional growth delay,” two diagnoses that don’t feel all that satisfying but essentially mean that there’s nothing medically wrong with your child. With familial short stature, a child is short because the parents are short, says Klein. Kids who have constitutional growth delay are often termed “late bloomers,” children who have families for which puberty tends to hit late.

Boys are two to three times more likely to receive growth hormone therapy than girls.

In both cases, the doctor’s plan is usually simple. “For kids like this, we’ll take a watch-and-wait approach,” monitoring growth and development over time, says Klein. (For some boys, a brief course of testosterone to jump-start puberty may be used, especially if they haven’t started puberty by 15 to 16 years old.)

When a disease is discovered, treating it may bring on a growth spurt as a welcome side effect. Such was the case in Robyn Friedman’s family. The mother of three who lives in New Jersey explains that tests on her then-12-year-old son, who had barely grown between his last few annual checkups, which is what prompted the testing, revealed that he was suffering from Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease that can stunt growth. “Once he began treatment for that, he grew 3 inches in a year,” says Friedman.

For kids with growth hormone deficiency, which can have a number of causes, an endocrinologist may prescribe injectable synthetic human growth hormone (GH) to get levels back up to where they should be. GH treatment is also used, somewhat controversially, simply to boost height in short kids with no deficiency — although the data on how much this helps this particular subset of kids is less clear. It’s FDA-approved but not often covered by insurance. The debate among doctors and parents over when to use GH and in which kids remains heated — with lingering questions over how much the shots can even help, and whether or not pathologizing stature has potentially negative ripple effects for both the kids and society’s perceptions and treatment of variations in stature overall.

The treatment isn’t that simple. GH treatment requires daily shots, sometimes for several years, and is extremely costly, often tens of thousands of dollars per year. (Insurance will only cover it for certain medical conditions.) An estimated 500,000 kids in the U.S. meet qualifying criteria for potential treatment —not that they all take it — and studies show it certainly can increase their adult height. (It is also used off-label by bodybuilders and others to aid in weight loss and building muscle mass.)

Side effects from GH treatment are very rare but can be serious. Headaches can occur because of increased pressure on the brain; if these happened, doctors would typically then halt the treatment to evaluate if it’s worth continuing. Other potential side effects include higher blood sugar, changes to the thyroid, and joint pain. Less is known about the very long-term risks of GH therapy, since it is a relatively new treatment. “Growth hormone was not approved for idiopathic short stature — short stature without a known cause — until 2003,” says notes Dr. Nadia Merchant, a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s National Hospital. “If someone received it for that reason, they can’t be much older than their 40s, so we don’t really know long-term risk.”

Somewhat ironically, one study found that short but healthy children who receive GH treatment may become more depressed and withdrawn than peers the same height who do not undergo growth hormone therapy, perhaps due to the experience of “daily injections, frequent clinic visits, and repeated discussions about height,” the study’s lead author, Dr. Emily C. Walvoord, of Indiana University School of Medicine, said in a statement.

In my daughter’s case, we started with a detailed look at our family history. We explained that I went through puberty on the late side, and my 6-foot-tall husband didn’t actually have his pubertal growth spurt until he was in college. (He grew nearly 6 inches after graduating high school.) His mother and sister both recounted not getting their periods until well into their teen years — much later than the median age in this country, which has dropped to just shy of 12 years old. We then moved on to blood tests, a bone scan, and then a test to stimulate her pituitary gland, to assess how well it’s pumping out growth hormone.

So far, there’s nothing abnormal in my daughter’s tests — and her bone age shows that her bones are far behind her chronological age, which bodes well. Without a true deficiency, the most likely conclusion is that there’s no underlying cause for my daughter’s height and that she too will be a late bloomer like her parents, although lobbying our insurance company to cover a trial of GH is a possibility, especially given how strongly my daughter feels about it all.

The emotional impact of height on kids

By the end of high school, I still endured comments about my height from random kids who were apparently shocked that I was in the “senior” hallway. Sometimes it felt like the only thing anyone noticed about me was how small I was. My middle-schooler experiences the same thing — consistent distress associated with feeling physically different than her peers. When it comes to size, my daughter just wants to blend in, but she doesn’t. When friends are shopping for clothes and dresses for dances and bat mitzvahs, she has a hard time participating because even the XXS at many stores will swamp her. And there are kids in the hall at school who feel the need to exclaim “Wow, you’re so short!”

Now that I’m an adult, my height isn’t really an issue, and many people tell me they don’t even realize that I am all that short. This reassurance that it will all even out someday, so to speak (and that there are even certain advantages, like finding a cramped airplane seat surprisingly roomy), is cold comfort to my daughter. And it likely would be even less comforting — and maybe not exactly true — for boys.

With my daughter and her younger sister, I have always quoted Shakespeare: “Though she be but little, she is fierce.”

Much like weight, “stature can have an outsized emotional component in our society,” notes Merchant. Klein agrees. “Both boys and girls who are smaller than their peers may experience feeling out-of-step or even excluded, especially with regards to sports.”

Molly (not her real name) in New York City, has three children — all of whom are short. “We are small people,” says Molly, who is 5-foot-3 to her husband’s 5 feet, 6.5 inches. But after her eldest child, a girl, dipped below the 1st percentile for height around age 12, they met with a pediatric endocrinologist. Through testing, she was found to have a deficiency in growth hormone production, and after nearly two years of daily injections of GH starting at age 13, she grew just over 4 inches.

Today her daughter is 17 and is just about 5-foot-1, an outcome that both Molly and her daughter feel happy with. “She’s not the tallest, but she’s not the shortest, and she is confident and pleased.”

And now, her 11-year-old son is also taking daily GH shots — his increasing distress about his diminutive size and slow growth plus the fact that, like his sister, he had a deficiency, led to their decision. “He’s both skinny and super small, and while it didn’t really upset my eldest daughter all that much, it is something he really cares about,” says Molly. “Based on experiences with my kids and friends' kids, I think boys are more likely to be bullied about their height than girls.”

Indeed, short boys may become short men. And often in our society, they have it harder than short women. Studies have shown that people, unfairly, may be biased against shorter men when dating or hiring for jobs. Perhaps that’s a factor in why boys are two to three times more likely to receive growth hormone therapy than girls.

But societal pressures needn’t dictate everything. With girls or boys, doctors like Klein and Merchant try to keep the focus away from the numbers, and try instead to emphasize the health of the child and pay close attention to how the kid feels about their own size. Although some do suffer emotionally, that’s not the case for all. “You’d be surprised how often the kid is actually OK with it,” says Merchant. (It bears noting that Merchant herself knows very well what it’s like to be small; she’s just over 3.5 feet tall, due to a genetic disorder.)

In the end, if your child is small, talk with your doctor about possible causes, have your child thoroughly evaluated, and listen closely to what your child says about their height, so it doesn’t become a bigger deal than it may already be. It’s a delicate balance, of course. As we’ve gone forward, I have worried, a bit, about all these tests and doctor’s appointments and hand-wringing. Are they confirming to her, in some way, that she’s not perfectly fine as is? I definitely don’t want to take our eyes off the most important goal here: that she grows a strong and impermeable sense of self. With my daughter and her younger sister, I have always quoted Shakespeare: “Though she be but little, she is fierce.”

Studies cited:

Sotos, J., Tokar, N. (2014) Growth hormone significantly increases the adult height of children with idiopathic short stature: comparison of subgroups and benefit. International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4114101/

Experts:

Dr. Michelle Klein, M.D., a pediatric endocrinologist in a private practice affiliated with Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City

Dr. Nadia Merchant, M.D., a pediatric endocrinologist at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C.

This article was originally published on