Pandemic Parenting

The Dads Are (Also) Not All Right

The pandemic was a crisis for mothers, but there has been an eerie silence on the topic of that other group deeply involved in parenting. So where the hell are the dads?

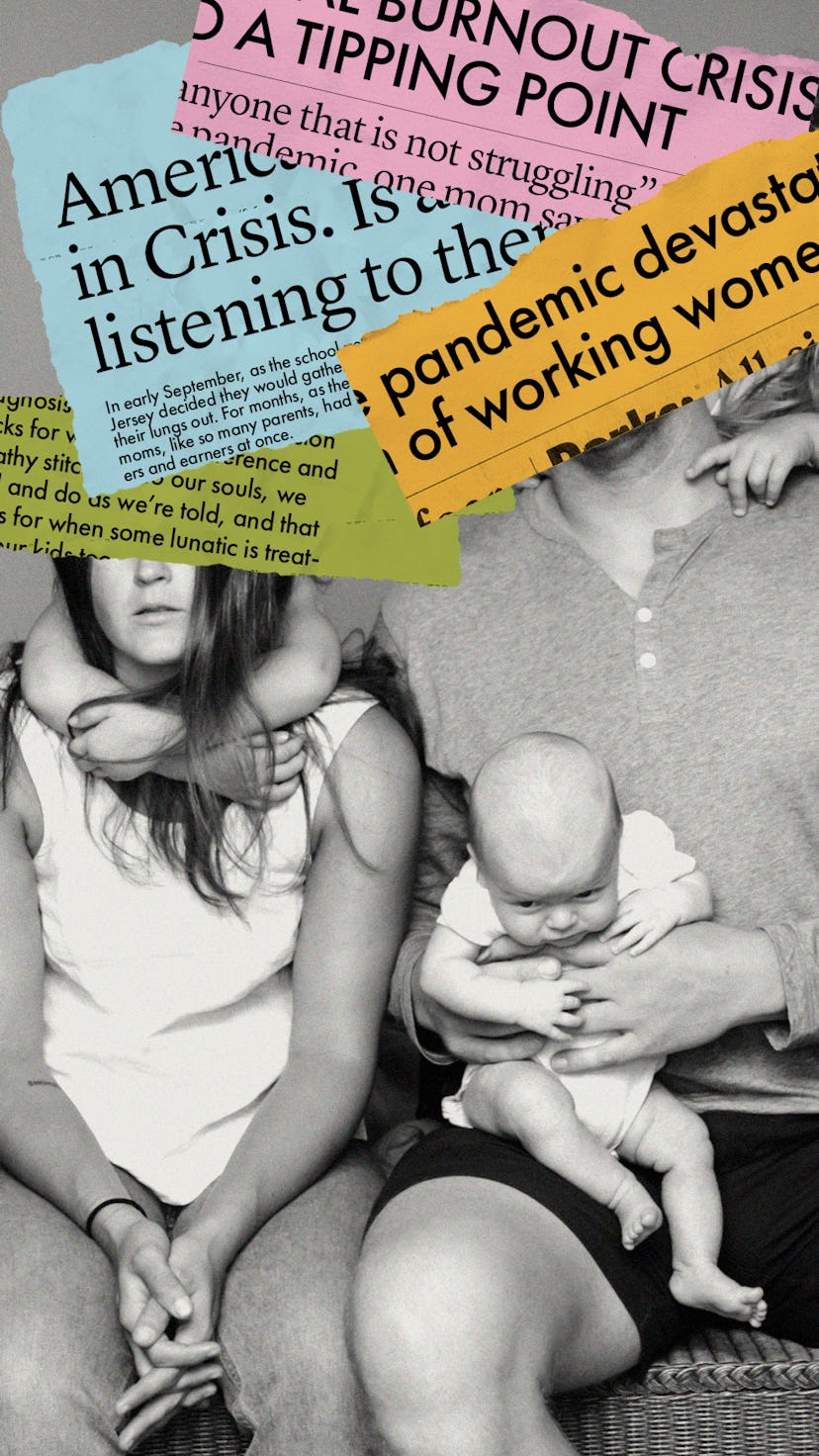

Parenting was never supposed to be like this: We heard that refrain over and over through 2020 and the early months of 2021. Anyone with kids or with friends with kids or really anyone who saw dead-eyed parents on a Zoom screen knew there was nothing sustainable about what was happening.

Parents have been overworked, overstressed, and crumbling under the pressure of being everything to everyone in a world that does very little to support families. Thankfully, the media has covered the story of this crisis of parenthood exhaustively for the past year. I personally found this a nice change from the days when the mainstream media scoffed at the concept of talking about caregiving at all outside of their soft features sections.

But one word has been missing from the majority of the coverage: “parent.” Let’s be honest: This year, the crisis of caregiving has been covered mainly as a crisis of motherhood, and with good reason. According to a March report from McKinsey, 1 in 4 women were considering leaving their jobs or “downshifting their careers,” versus 1 in 5 men. The report identified the three groups of women most affected by the pandemic: “working mothers, women in senior management positions, and Black women.” The disparity was particularly extreme for parents of kids under 10.

The media took notice. Last September, NPR did a segment on working mothers reaching their breaking points. The New York Times did their excellent series on the primal scream of motherhood, literally setting up a phone line where mothers could call in and scream at the top of their lungs. An accompanying podcast from The Daily provided additional narratives on the agony of pandemic motherhood. The March 15 cover of Time magazine told us all about “The Fight for Working Mothers.” The Atlantic recently covered the professional women who are leaning out of the workforce and embracing part-time work because of the pandemic. The Washington Post ran an opinion piece about how the pandemic has devastated a generation of working women. A Vox story in December did bear the headline that “the parental burnout crisis has reached a tipping point,” but the story did not quote a single father.

These are stories that need to be told (I wish motherhood were covered every single goddamn day on the front page of the New York Times), but where the hell are the dads?

NPR did do a sweet feature entitled, “‘I’m A Much Better Cook’: For Dads, Being Forced To Stay At Home Is Eye-Opening,” And Today’s Craig Melvin highlighted three frontline worker dads in the pandemic, but for the most part, the media coverage of this crisis has focused exclusively on mothers. What has been largely missing from the narrative is how fathers coped. Did they also take on new burdens and if they didn’t, why the hell not? Did they suffer the way mothers suffered?

I find this fact especially ironic since it is typically women who are written out of historical narratives. This pandemic has indeed been disproportionately hard on women and on mothers, but the media is clearly more comfortable with talking about women as caregivers and their role as parents. “The media is caught in the same old sexist assumption that ‘home’ is feminine. And so, parenting is still a mothering issue,” Jordan Shapiro, author of the upcoming book Father Figure: How to be a Feminist Dad, told me. “It's OK for a man to be the distant doctor/authority, but a father combining experience, intuition, and expertise is out of alignment with the cultural expectations. Leaving fathers out of the current media narrative normalizes the inequity of household care labor, which is not only a misogyny problem, but also stigmatizes the dads who are trying to do the right thing.”

“We are conditioned to think that we are weak if we talk about anything but ‘crushing it’ and living our perfect little lives.”

So I wanted to hear from dads. Are fathers also at the end of their ropes? Were they squeezed inexorably by additional chores and familial duties or the stress of overseeing home schooling efforts? Did they feel their careers were in peril? Are they experiencing the primal scream? Do they see this past year and a half as a parenting crisis, one that challenged their assumptions about domestic duties and their value as full-fledged members of the economy?

When I put the question out there, I got as many types of answers as there are kinds of dads. There are plenty of fathers who found ways to continue this year as if life has not been disrupted at all. Those dads locked themselves in a home office or spare bedroom all day and came out at 6 p.m. as if they'd just stepped off a commuter train in 1955. For the most part, they still do not recognize the imbalance of emotional duties that mothers take on.

I spoke to one dad at a party who mentioned the pandemic in almost glowing terms, how it brought his family so much closer together because they were all under the same roof all the time, how he got to be there for Zoom band concerts and a virtual school performance of Little Shop of Horrors. Separately, his wife told me she wanted to f*cking kill him. “He spent all day, every day in our basement while I did Zoom school for three f*cking kids and somehow managed not to get fired.” I asked her if they’d talked about how different their two perspectives on the pandemic had been and she said she was simply too exhausted to bring it up.

I'm desperate to know where any father gets off not stepping up in this crisis. I wish that every story we read about a mother at the end of her rope explained where the hell the man in her life was and why he wasn't being held accountable. Was he a jerk? Was she afraid to ask him for help? Were they both trying but the whole situation was so devastating that everyone had been flattened?

There were, of course, plenty of fathers who told me they were not OK — that they too felt overwhelmed and overworked, that they were falling behind in their jobs, that they felt like they were failing their children. Many men started out by saying they didn’t want to admit they weren’t fine. Most told me they felt too ashamed to talk about how they were flailing.

“I feel guilty even saying dads struggle but we do — at least I do,” BJ Nowell, a father of three and a partner in a big consulting firm, told me. “We are conditioned to think that we are weak if we talk about anything but ‘crushing it’ and living our perfect little lives.” (BJ Nowell is not his real name. He asked that we use a pseudonym because he felt he could be more honest if he didn’t have to deal with repercussions at work.)

Nowell and his wife have three young girls, the youngest of whom was born during the pandemic. They both have demanding jobs and both feel like they’ve fallen behind in them. “From a career perspective, I definitely had my most challenging year in my time at any firm. It will take me years to get back to the level I was pre-COVID,” Nowell said. “My wife has really struggled. Firms aren't kind to women who want to be moms, regardless of how talented or how many years of top performance they have put in the books. So I feel guilty about that too because I want to be able to take care of the kids and support her. But we run out of capacity at some point. I think that left a couple of people like zombies, neither having an outlet, and in my case a guy not wanting to show any cracks because you feel like you are the one holding things together.”

Experts say they have seen a rise in anxiety among both mothers and fathers equally, but men are much less comfortable being vocal about it. “I would say the increase in anxiety, depression, loneliness, and attempted suicide has been about 200%,” said Matthew Weldon Gelber, a psychotherapist in Devon, Pennsylvania. “Men generally are more reluctant to believe that they have behavioral health issues but I have seen in the last year men addressing the issues equally as women and finding themselves depressed and needing help psychologically.”

“I've cried. I've been unstable. I've wanted to have my Network mad-as-hell moment. I've not wanted to work,” says Evan, a 34-year-old middle school teacher in Novato, California. Evan has three children of his own, all of whom are being home-schooled while he teaches sixth grade virtually. In the past six months, teachers in his community, and nationwide, have been alternately praised and vilified on social media and the news. He feels like he is constantly teetering on the edge of his sanity.

“I've considered leaving teaching, as many have demonized us as selfish or ‘inconsiderate’ of the needs of the students,” he said. “All the while, I've got to power up the laptop, turn on the Zoom meeting, and be energetic and ready to discuss ancient Mesopotamia with my sixth-grade students who just want to be able to hang out with their friends. I've been drinking much more regularly. I've been using marijuana. I was a once-or-twice-a-year sorta guy. Now, it's a habit.”

“I've had the chance to say ‘I love you’ so much more these past 12 months, but I've also had to say ‘I'm sorry, I shouldn't have reacted that way,’ far more times than I ever should.”

And all of this stress trickles over to his parenting, which makes him feel like he is failing his own children on a daily basis. “My children have not always seen the best of me. We've been able to spend lots of time together, but my fuse is shorter. I'm so frustrated with the demands of work, and the critiques of the public, that I've taken it out on them far too often,” Evan says. “I've had the chance to say ‘I love you’ so much more these past 12 months, but I've also had to say ‘I'm sorry, I shouldn't have reacted that way,’ far more times than I ever should. It's become a mixture of pride and embarrassment as a father working from home. I've tried my best to adapt, but I was not ready for the steep learning curve.”

The national media conversation about pandemic parenting has given us many examples of the struggles of single mothers, but very few of single fathers. Matt and his wife of 16 years separated during the pandemic. He has his three kids on his own half the time and admitted that he is constantly scrounging for some sense of control. “This is particularly acute when I've got to be the headmaster of our virtual school and manage my own career by scheduling interviews and work once the kids are finally asleep,” he said. He added that he has recently joined a virtual support group moderated by a psychologist to try to maintain his mental health. He also asked that we only use his first name in this article.

“Still, I always feel like a failure of a parent setting the kids up with screens so I can go and talk to people for 90 minutes,” he said. Despite his struggles, at the end of the day Matt still thinks that mothers have it worse and he doesn’t want anyone to throw him a pity party. “I don’t feel left out of the conversation,” Matt told me. “Because this situation truly does f*cking suck for working moms.”

Indeed, the statistics about working women exiting the workforce show that more women are taking on the role of the primary caregiver. From February of 2020 to February of 2021, approximately 2.4 million women left the workforce compared with less than 1.8 million men. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t fathers taking on the role of primary caregiver; we just rarely hear those narratives. While I don’t think we should be lavishing special praise on men for doing the ordinary work of parenting, I do think it’s important to highlight the men who’ve stepped up during the pandemic. It’s a crucial step to normalizing dads as the primary parent.

Prior to the pandemic, Adam Braun worked as a physical therapist; his wife had an executive-level position. Last March they talked about what made sense financially for their family and concluded that with their son home from day care, Braun should stop working and be the primary caregiver. Until then they had mostly shared parenting duties equally but Braun’s wife took on most of the emotional labor that included meal planning, long-term plans, and overseeing a social calendar. Suddenly, all of that was Braun’s job.

“I needed to take on more of the emotional labor and this was hard for me. It still is and it requires nudging, but it was important for me to hear her. She continued to work full time and probably worked harder than when she was commuting into the city. I think that in order to be a successful co-parent and partner, these conversations need to happen,” Braun says. “I have to give a lot of credit to my wife who continues to push me to be a better individual, a better husband, and better parent.”

It’s these kinds of conversations that have the opportunity to fundamentally change things when we return to “normal” — or whatever lies on the other side of the pandemic. “There has to be a willingness to take a critical perspective and recognize places where we are reproducing old gender patterns. Men are often bad at recognizing that because it doesn’t serve them to recognize that,” Shapiro told me. “It’s hard when you go through life imagining yourself as the hero of the story to suddenly recognize yourself as the villain. We have read a thousand articles about the emotional labor that falls on women, but men need to work on this and say ‘where do we make gender assumptions and how do we change them?’”

I think the current focus on mothers is mostly an overcorrection to a hundred years of media that did not take women and mothers seriously. That overcorrection was sorely needed, but this cannot be a place we leave out men. We just can’t. We need to include fathers in this conversation because if we don't include them, there is no way they can be full partners in what comes next. This isn't about returning men to the center of any conversation (I would never) but about making sure they are equally responsible for the solution — and feel the urgent need for one. If we consistently frame this as a crisis of motherhood, we put the onus on mothers to solve it.

Jo Piazza is the best-selling author of Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win, The Knockoff, and How to Be Married, and hosts Under the Influence, a podcast about moms on the internet. She is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and New York magazine, among many others. She lives in Philadelphia with her husband Nick and their two children.

This article was originally published on