Nothing Can Prepare You

Emily Oster Helped Us Expect Better. What If The Worst Comes To Pass?

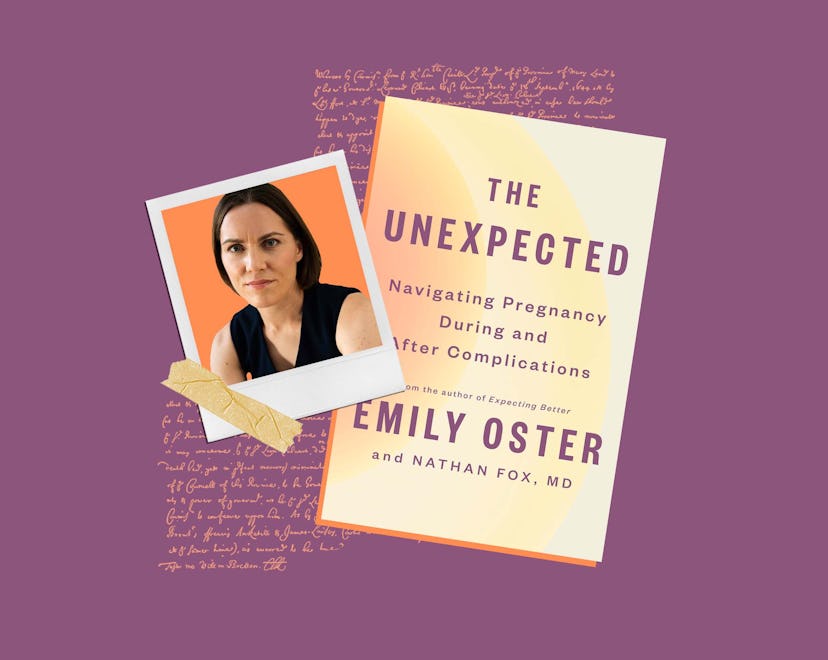

The Unexpected, Oster’s new book with co-author Dr. Nathan Fox, M.D., takes on pregnancy anxieties that can’t be dismissed by data.

Shortly after I gave birth to my first son, the room filled with a scramble of doctors. The delivering obstetrician inserted both her arms up to her elbows into my vagina attempting to stem the bleeding. I passed my baby from where he lay on my chest to my husband as I started to lose consciousness. Finally, a nurse pushed something into my IV line. I snapped back to attention and threw up. The crowd left the room, and nobody spoke of it again.

It wasn’t until two years later, when I read Emily Oster’s new book, The Unexpected, that I understood the seriousness of my postpartum hemorrhage. Receiving this clarity from Oster and not my very good OB-GYN felt like a sign of how much is lost when medical appointments are limited to 15 minutes, as well as a testament to Oster’s talent for bridging the knowledge gaps surrounding maternal medicine.

In the 11 years since the release of Expecting Better, Oster’s blockbuster book that assured pregnant people it was totally fine to have a glass of wine, the author and economics professor has become known for putting a big asterisk next to conventional medical advice when it is rooted in slim research or when it discounts the other risks informing people’s decisions. Her 2019 parenting book, Cribsheet, debunked claims that breastfeeding led to higher IQs, and during the height of the pandemic, she was one of the loudest advocates for reopening schools. In The Unexpected, out April 30 from Penguin Press, Oster’s intervention is to provide what the medical establishment often does not.

With her co-author Dr. Nathan Fox, M.D., a New York City maternal fetal medicine specialist, Oster explains pregnancy complications ranging from hyperemesis gravidarum to stillbirth, outlining possible causes, the probability of recurrence, and treatments shown to mitigate risk. She advises patients on how to structure conversations with their doctors, with practical advice (how to obtain medical records) sitting alongside more touchy-feely material (brief, compassionate guidance in coping emotionally with trauma).

These are not topics that can be waved away by pointing to their unlikelihood or worked through using one of the decision-making frameworks in Oster’s 2021 book, The Family Firm. Nor will anything she and Fox say radically upend your understanding of pregnancy complications. But by sifting through large amounts of data and communicating the information clearly, Oster assumes the role that has made her ParentData newsletter and podcast essential to so many: She is a guide for parents deciphering advice during the most anxious times in their lives.

Below, Oster discusses the new book, how doctors and patients can have better conversations, and why sleep training might be a treatment for postpartum depression.

Romper: Why did you decide to return to the topic of pregnancy?

Emily Oster: Over the decade since Expecting Better has come out, I’ve talked to a lot of pregnant people, and I’ve been there for a lot of the good experiences but also the hard experiences. So many of the questions I get that are most fraught are “This happened before; will it happen again?” or “I’m having this complication; how do I navigate it?” And it felt to me that’s the book that was needed.

Romper: Throughout all your work, there’s an attempt to mitigate pregnancy or parental anxiety. How does writing for an anxious reader change when you’re tackling the bad, the really horrible, head-on?

EO: I write so much for people who are anxious. It’s a feature of parenting, and a lot of how I approach ParentData or even Cribsheet or Expecting Better. There, I’m trying to reassure people that it’s unlikely something bad will happen. In this book, we’re kind of coming in the other direction, which is something bad did happen. And so now, how do I move forward? We begin with a lot of what my co-author, Dr. Nathan Fox, would call radical acceptance. Rather than saying “try not to worry” to say “OK, let’s contextualize that worry.” We can try to adapt to its existence, to accept that it’s there, but still make good decisions and still make choices that work for us going forward.

"With all the data in the world, I still think it’s going to be a long time before we understand why someone has miscarriages and someone else doesn’t,” Oster says.

Romper: To what extent do you think your book grew out of how our medical system is structured, with the limited amount of time patients have with their OBs?

EO: It’s a sort of slightly odd situation where we’ve moved to talking a lot about shared decision-making, and the idea that patients should be involved in these decisions, and yet we haven’t given people the time or resources to be equipped to have those interactions. I think some of this book’s structure is saying “Here’s some information.” And then telling people, “After you’ve reflected on this, when you come into your provider, you should have some questions. And here are some suggested questions. Here are some ways you might structure the conversation.” From the medical provider perspective, this should also be very valuable because doctors want their patients to make decisions that work for them and want their patients’ preferences to be respected. It’s hard to have that happen if you are also trying to teach a lot of information all at once.

Romper: How has this experience differed from writing Expecting Better, where you weren’t necessarily in complete agreement with medical advice? Here, you’re more in lockstep with Nate.

EO: Actually, the way that Nate and I originally met is that he wrote a piece for a medical journal about how many restrictions in pregnancy were overblown. When I read Expecting Better now, I can feel the frustration that I had with the medical system. I think Nate helped me understand that we can actually do this better in more lockstep, and that the sort of conflict that I felt, which I think was very real, we could reduce. Maybe if I had seen Nate as my first provider, there would be no Expecting Better.

Romper: Were pregnancy complications harder to report on?

EO: There were many places in The Unexpected where ultimately what we say is like “This is just random” or “We don’t know why this is happening to you.” People would like to have answers. I think that's very hard for patients, and this is what I found hard about writing the book. What if we looked more in the data? But even then, it’s up against some of the limits of how we understand basic biology. With all the data in the world, I still think it’s going to be a long time before we understand why someone has miscarriages and someone else doesn’t.

I always think we could study pregnancy complications more. The set of things that are probably less studied are things like hyperemesis, where it’s a symptom. It does have a medical component, but a lot of it is kind of a way that people feel, and that is something that we never pay attention to.

Romper: It seems like whenever a woman is expressing a feeling, it’s easier to dismiss.

EO: The hyperemesis is a really interesting example because in the last year, there was a reasonably important new finding about the role of a particular hormone. That research was done by someone whose hyperemesis was dismissed by her doctor. And she was like, “I’m going to fix that.” And that’s not a good way to motivate research. We shouldn’t just be waiting for people to develop complications who happen to also be medical researchers to find out the answer.

Romper: You talk about postpartum depression in the book and the likelihood that it will happen again. Have you seen any data about causes and treatment for postpartum depression, things that were more successful than others?

EO: The number one risk for postpartum depression is prior depression. So that suggests an important chemical component. But then, when we look at other risk factors, there are things like how much does your baby sleep and how much support do you have. This suggests that trying to intervene on some of these other factors or being aware of some of these other situational factors could also address some of this depression. For example, a lot of the randomized trials for sleeping training are intended to treat postpartum depression.

Romper: In the introduction, you say the middle sections of the book, those that address specific complications, are meant to be used as a reference. What are some of the problems with the pregnancy reference ecosystem on the Internet?

EO: If you sort of said “Well, how can I learn about what preeclampsia is?,” you can definitely get that online. But the second piece — how likely is it to recur and what are some of the treatments? — it’s often not that specific. Then this last piece, which is how do you take all that information and convert it into a conversation that you’re going to have with your doctor, I didn’t see that anywhere. That’s a huge barrier to many of these conversations.

Romper: Since the release of Expecting Better, you’ve become a household name in parenting circles. Sometimes you’ve advocated for things that were polarizing in the moment and then more people have come around to. The obvious example is schooling during Covid. What has that experience been like for you?

EO: My college roommate, after one of those Covid things, told me, “You’ve pioneered a new way of being wrong, which is being right but six months too early.” Certainly, there were times during the pandemic that were very hard, and there’s still times that it’s hard. I think I’ve gotten better as a person about having a thicker skin, thinking about which pieces of criticism I should take inside the house, in the kind of Glennon Doyle sense, and which should stay in the mailbox. But when I reflect on this moment and what I’m doing, I’m still surprised that this is where I’ve ended up.

In economics, we talk a lot about comparative advantage and people doing the thing that they’re relatively the best at. What makes me happy is I feel like I found that thing. I’m a good economist, not the best economist in my house, but I’m a good economist, but I’m better at helping people understand how to apply data and research to their everyday lives. This is my comparative advantage. I think getting to find that and do it and feel like it helps, at least some people, it’s a gift.

Romper: Initially you were writing books. Now, you are the CEO of a multimedia parenting platform, ParentData, that has a podcast, a newsletter, and other writers. You also have more personal ventures: You’re also doing front-facing videos on Instagram; you have a capsule collection at M.M.LaFleur. How are you finding these different approaches, in terms of your ability to reach your audience?

EO: One of my life goals is to help people understand that correlation is not causality. For example, screen-time associations with outcomes are not all causal. That’s something I think everyone should understand because then when they see the headline that’s like “Screen time ruins your child,” they’re not like, “Oh, my God, I’m a terrible person.” I think a lot of these different avenues are really about trying to figure out the best way to talk to a larger public about these core ideas in data literacy — and how we can make them fun.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.