Pregnancy

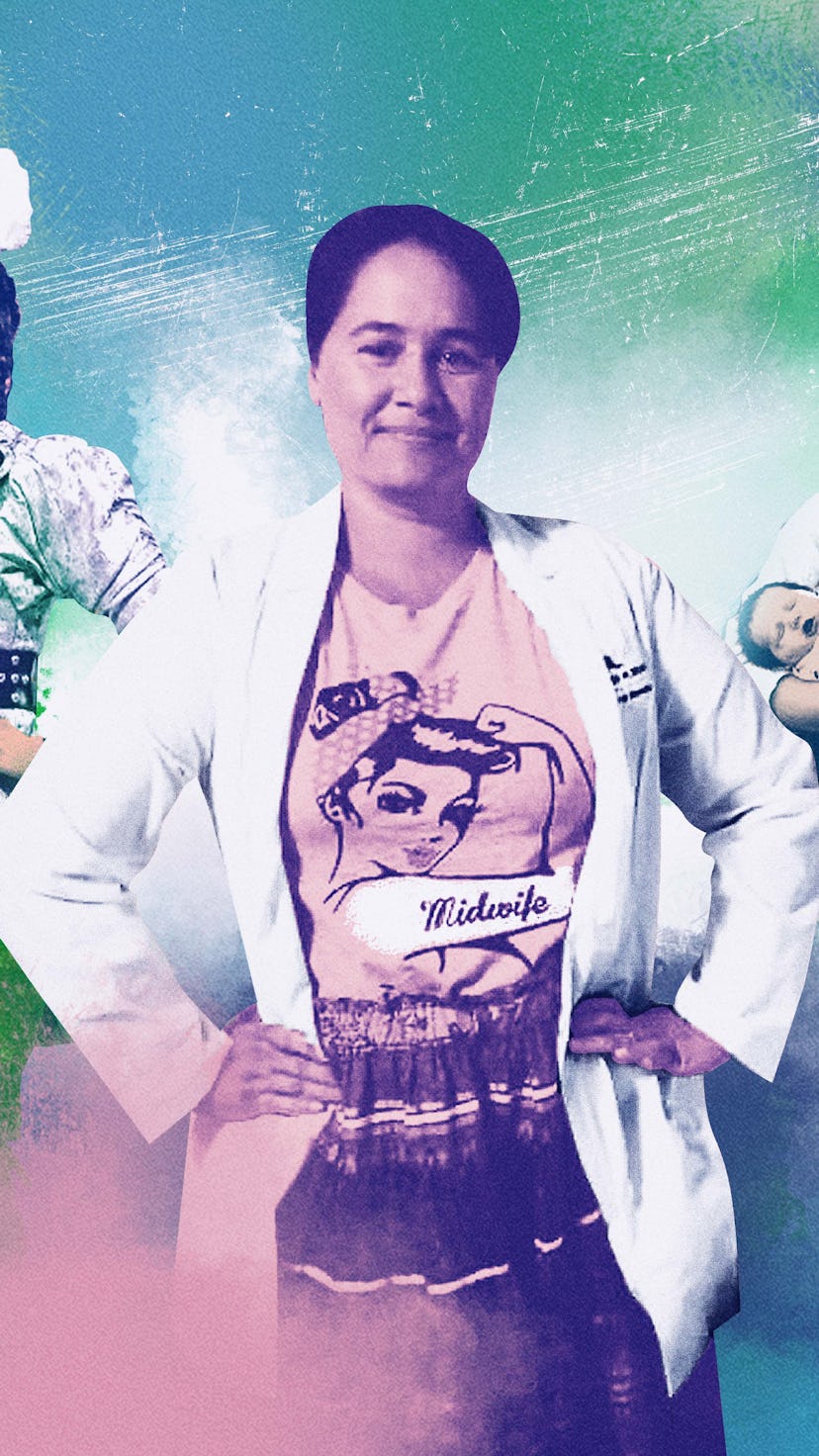

The Midwife On A Mission To Revitalize Indigenous Birthing Practices

Rebekah Dunlap didn’t realize how disconnected she was from Ojibwe birthing traditions until her son was born in a hospital in 2007.

Rebekah Dunlap didn’t realize just how disconnected she was from Ojibwe birthing traditions until her son was born in a hospital in 2007.

Although the 45-year-old Two Spirit nurse midwife grew up on Minnesota’s Fond du Lac Reservation, her family lost touch with these customs generations back, when her late grandparents’ boarding school experiences stripped them of their cultural knowledge and supplanted it instead with Catholic teachings. It was while Dunlap was raising her infant son as a single mother that she made it her mission to decolonize Native American birthing practices, including her dream to open the first birth center on a U.S. Indian reservation.

Indigenous women experience outsized barriers to maternal care, such as limited health care choices due to insurance coverage, far traveling distances to hospitals, and marked discrimination once in those settings. On top of that, they face woefully stark health disparities: They’re more than twice as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as white women, while Native infants die at nearly twice the rate of white babies. Driven by these dire realities, Dunlap is part of a growing movement led by Indigenous midwives, doulas, and health care providers to reclaim Native birthing traditions. They hope to revive communal ceremonies in place of the often impersonal clinical procedures performed by providers who don’t always fully understand their patients and may even have biases against them.

“I believe that a return to our sacred ways can really make a big impact on the survival of our people,” explains Dunlap, a 2022 Bush Foundation fellow. “We have a lot of beautiful ceremonies surrounding pregnancy, birth, and postpartum, with men, women, and the whole community involved. For example, when somebody is in labor, we have fires to light the way for that spirit, with people praying and singing songs. We use plant medicines to help with certain health concerns. Then afterward, we have practices to bring our own spirits back into our bodies.”

Dunlap’s desire to serve others began early and was inspired in part by her frequent childhood visits to the reservation clinic, which was little more than a modular trailer. She remembers at a young age feeling nervous around the often white male providers, who didn’t resemble anyone she was used to seeing in her community. “But there was a Native receptionist who made me feel really safe and comfortable, and I hoped someday to be that person in my community,” she says.

Coming from a poor family with little formal education, Dunlap recalls struggling as a first-generation student. She dropped out of high school but eventually got her GED and then her licensed practical nurse (LPN) certification. Once she realized her life’s mission was to decolonize Native birthing practices, Dunlap went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in nursing, an Indigenous lactation counselor certification, and, most recently, a doctorate in nurse-midwifery.

“Native peoples’ mortality rates in hospitals are just too high, and I strongly believe that Indigenous birthing practices are going to save us.”

It was her own childbirth experience back in 2007 in a hospital setting with modern medical interventions that caused Dunlap to really contemplate how her grandmother’s boarding school ordeal had all but erased Ojibwe birthing and lactation traditions within her family’s history. Soon afterward, she began seeking out answers from tribal elders and, in doing so, realized that many people within her own community misunderstood or even had a negative impression of these cultural practices. Dunlap sees this as one of the many pervasive damaging effects of colonialism.

Dunlap says her time as a doula was particularly eye-opening. Around the time her son was born, her tribe serendipitously debuted a doula program, which she joined a year later. Through this work, she regularly witnessed the microaggressions Native women face in hospital settings, such as not being allowed to observe tribal religious beliefs, like burning plant medicines or having a spiritual leader present, while customs rooted in Christianity were often permitted.

Rather than getting discouraged, Dunlap got motivated: “I wanted to teach providers what all of this meant so that they were more educated and more comfortable in hopes that we could bridge that gap and do some mending,” she says. “I thought with a bit more understanding, perhaps the care would be different.” Early on, hospital staffers were often confused by her role as a tribal doula, but she continued to make what she calls “gentle nudges” to introduce traditional Native practices into these spaces.

Her efforts over the course of nearly 15 years have certainly paid off. Today, the two Duluth hospitals Dunlap has worked most closely with have implemented major changes: Signage in Dakota and Anishinaabemowin, the Ojibwe language, now welcomes Indigenous clients in their tribal languages. Artwork adorning the walls is more culturally appropriate. And policies permit the burning of sacred medicines, with the assistance of on-site maintenance staff.

During those 15 years, Dunlap has become regionally renowned for her birth work and now attracts clients from across Minnesota, like 28-year-old Kwe Humphrey, a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe who today works as an Indigenous culture coordinator at a local school (including developing relevant curricula, engaging tribal guests to speak to students, and acting as a liaison between the school and Native families). When she became pregnant in January 2020, Humphrey knew she wanted to incorporate Anishinaabe customs into her childbirth experience. She was feeling particularly alone at the time, in the process of leaving an abusive relationship and living in low-income housing far from her family. Then the pandemic hit.

“I thought with a bit more understanding of tribal birth practices, perhaps the care would be different.”

“Between a toxic relationship and the isolation, I really didn’t feel witnessed while creating life, but Rebekah made me feel witnessed,” Humphrey explains. She had originally planned on a home birth in a lodge Dunlap’s family built on their property near Bemidji. But after 45 hours of laboring, Humphrey opted to go to the local hospital. Dunlap was right there with her, even with stringent Covid restrictions.

“I wish that I didn’t end up in the hospital, but I felt so protected having Rebekah there,” she says. “I was in an insane amount of pain, I hadn’t eaten and I hadn’t slept for two days. Because Rebekah has experienced so many births in hospitals, she was able to explain everything to me and communicate my needs. I was so grateful she was there.” Although they weren’t able to integrate many traditional elements into Humphrey’s childbirth given its urgent nature, Dunlap’s son kept a fire burning for her and Dunlap brought her nourishing tribal foods to eat, like bone broth infused with nettle and goji berries as well as wild rice with berries and maple syrup.

Humphrey acknowledges that without a supportive partner by her side, Dunlap filled that position during her time of need. “In many ways, Rebekah and my sister stepped into that role: cooking for me, staying up all night with me, holding my baby so I could sleep,” she says as she starts to tear up. “We need more people like Rebekah delivering babies and taking care of postpartum people. Native peoples’ mortality rates in hospitals are just too high, and I strongly believe that Indigenous birthing practices are going to save us.”

Dunlap takes that sentiment one step further, connecting the birth work she’s doing to land sovereignty. “We can’t survive without our Mother Earth and everything she provides, and we need to be good to our land, our soil, and our waters because it all directly impacts us,” she explains. “It impacts the sacred water our babies are carried in for nine months, and it impacts the colostrum, which is the first medicine they get when they’re born.”

Although she’s a vital driving force in the movement to decolonize tribal birthing practices, Dunlap emphasizes that it will take a great community effort, including tough anti-racism work from Natives and non-Natives alike. She’s encouraged by the burgeoning presence of Indigenous voices in spaces where they’ve not been heard to date, pointing to the record number of Native Americans holding political offices.

For her part, Dunlap is spending the next two years as a Bush fellow to learn from tribal elders and other knowledge keepers in an effort to “decolonize my own mind and reclaim my birthrights as an Anishinaabe person so I can disseminate our traditional ways back into our communities and to our land.”

This will, in turn, inform Dunlap’s work to make her dream a reality: to open the first birth center on a U.S. Indian reservation. Not only would this allow Native women to freely incorporate traditional practices and teachings into their childbirth experiences, but it would also grant them ready access to vital prenatal and maternal care within their own community. As it stands, unless an Indigenous mother has a home birth, she must leave her reservation for the delivery of her baby.

In Dunlap’s vision, the birth center will be housed on the Fond du Lac Reservation in the large home her great-grandparents built in the early 1900s and that her grandmother owned until her passing. Thanks to its size, it was the site of many treaty signings, business meetings, and significant community gatherings. Surrounded by medicinal plants, it will offer tribal members an alternative to giving birth in a mainstream health care setting. Having a licensed professional like a midwife overseeing the customized care plan further reduces barriers, as this allows for health insurance coverage. Dunlap imagines sacred medicines being burned, community members gathering and bringing gifts, and beautiful creation stories being made.

It would be a full-circle opportunity for Dunlap to pay homage to her grandmother, a boarding school survivor, with a historic birth center that restores some of what her tribe has lost over time. “Grandma always said how she would love to have that place filled with life like it was at one point,” she says. “What a beautiful honor it would be to create a space that’s both culturally appropriate and medically safe and sound for the community.”

An Alaska Native Tlingit tribal member, Kate Nelson is an award-winning writer and editor based in Minneapolis. She currently serves as Editor-in-Chief of Artful Living, a top independent boutique lifestyle magazine. Her writing has appeared in ELLE, Esquire, Teen Vogue, Bustle, Saveur, and other national publications. A lifelong storyteller, she's also an avid equestrian and a pop culture junkie.

This article was originally published on