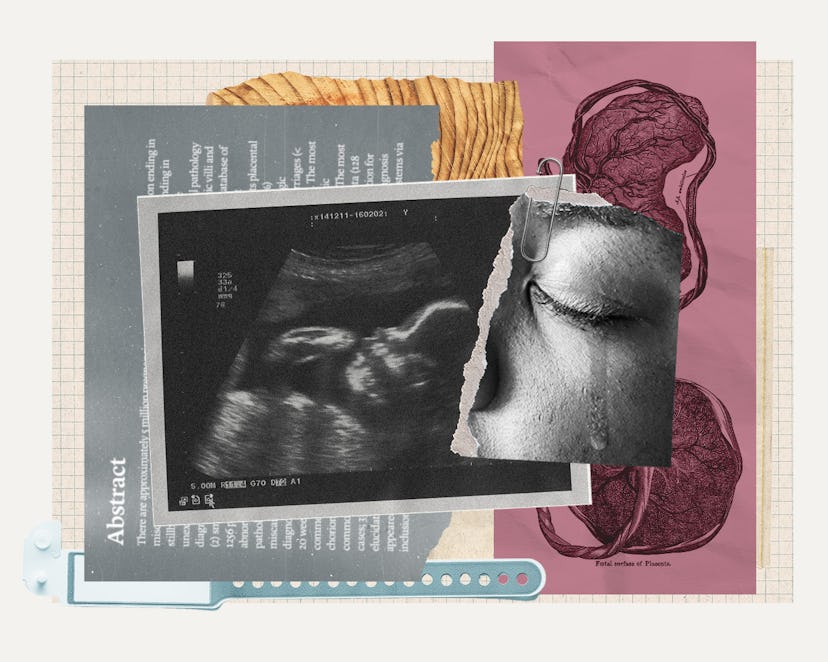

loss

If This Pregnancy Screening Could Prevent 30% Of Stillbirths, Why Is No One Using It?

The standard of care for pregnant people is a very difficult thing to change.

It was the summer of 2018, and Ann O’Neill was pregnant with her fourth baby — another boy. By all standards, this pregnancy, like her others, was healthy and low risk. On the morning before her due date, she noticed her baby had stopped moving. She didn’t want to be perceived as the “stereotypical, hysterical pregnant woman,” but she headed to the hospital anyway, just to be safe. It was there that a doctor told her her baby no longer had a heartbeat.

O’Neill delivered her son, Elijah, the following day. He was born at 8 pounds and 13 ounces, and the OB-GYN could not explain why he had died. “I was terrified initially to look for answers," O’Neill told me, but she requested an autopsy, genetic testing, and for labs to be run on her placenta. “I thought for sure I had done something wrong, but I didn’t know what. I didn’t eat lunch meat. I didn’t change kitty litter. I thought I had followed all the rules. He died and I was the one caring for him, so I thought it must be my fault.”

Three months and one long, confusing pathology report later, there was still no clear explanation for Elijah’s death. Then, in mid-October 2018, just weeks after receiving the fruitless pathology report, O’Neill’s ears perked up while she was listening to a podcast called Stillbirth Matters. A placental pathologist was explaining that small placentas can cause a stillbirth. He claimed that about a third of stillbirths could be prevented with a simple new screening tool he had developed through his work as the director of the Reproductive Placental Research Unit at the Yale School of Medicine.

Elijah had had a very, very small placenta, O’Neill remembered. The pathology report said it was below the 10th percentile. Why had no one checked her placenta size during her pregnancy? O’Neill immediately reached out to the podcast guest, Dr. Harvey J. Kliman, M.D., Ph.D.

Any loss of a baby after 20 weeks gestation is considered a stillbirth. Each year, there are approximately 21,000 of them in the United States according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (By comparison, sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS, takes approximately 1,400 lives per year.) Few parents are counseled about the possibility of a stillbirth during their pregnancy, though many hear a lot about how to prevent SIDS. In the early 2000s, Kliman had already been working at Yale for a decade, and had established himself as a leading placental researcher, when he investigated three stillbirth cases in a row that all followed a pattern: An OB was being sued after a stillbirth by a patient who argued that their doctors should have done something to prevent it, and the reason for all three tragedies came down to a small placenta. But there’s no way the doctors could have known, Kliman’s Yale colleagues told him, because there was no way to calculate the size of the placenta on an ultrasound. It’s a yarmulke-shaped organ, Kliman explains, that is hard to measure on an ultrasound because it doesn’t lie flat in space.

Kliman, who tends to speak in a professorial tone and quizzed me about my qualifications during our phone calls, took the problem to someone he thought could help: his father, Merwin Kliman, a NASA engineer who built the computers on the Voyager 1 and 2 space probes. (Kliman is very proud of his family’s achievements. He told me that his daughter, Laura, worked on the chemistry for the patented Impossible Burger. Kliman himself has 10 patents in his field, according to his Yale bio.) The elder Kliman was intrigued by the problem and came back to his son with an equation to calculate a placenta’s size on ultrasound.

Even with a small placenta, a baby will continue to grow normally — until all of a sudden, they can’t.

This equation launched Kliman into a decades-long quest, first to prove that the estimated placental volume (EPV) measurement is accurate, and second that it should be offered to all pregnant people.

While the majority of stillbirths go unexplained, Kliman analyzed pathology reports from close to 400 stillbirths and found one-third of the infants had small placentas (defined as being below the 10th percentile). In the realm of placenta research, it’s agreed upon that small placentas correlate with adverse outcomes for babies, and that identifying them would be one of the fastest ways to reduce the stillbirth rate. A placenta that is too small poses a stillbirth risk because, as a baby nears their due date and peaks in size, the placenta can no longer sustain their life.

Kliman compares the placenta to the kidneys: You can donate one kidney and still have normal renal function. In fact, you could then lose most of your remaining kidney before its function is ever majorly impacted. But once it gets too small, every percentage makes a massive difference. “In other words, it crashes. It’s a cliff, like a rubber band that stretches and then finally breaks. And that's exactly what happens with the placenta,” he says.

Today, OB-GYNs track the size of the fetus throughout the pregnancy, which Kliman describes as “a surrogate [measure] for the overall health of the baby.” However, even with a small placenta, a baby will continue to grow normally — until all of a sudden, they can’t.

After O’Neill reached out to Kliman, he did his own pathology report on her case. Her placenta wasn’t just barely below the 10th percentile, he found: It was in the third. “He said everything else looked clear. It had to be this small placenta,” O’Neill says. “As a mother, asking what could have prevented this is a pretty obvious next step.” That’s when Kliman told her about EPV. “Of course, I’m like, ‘Well, I had two third-trimester ultrasounds. Why didn’t they do it?’ It's so simple. It takes 30 seconds. The placenta is the life-sustaining organ of the fetus. To not look at it is unacceptable,” she says.

Kliman imagines a sonogram tech taking the EPV measurements as standard of care at every anatomy scan and in cases of decreased fetal movement. Let’s say you feel decreased movement at 32 weeks gestation. Your baby is measuring in the 60th percentile, and your placenta is in the second. “We’re going to do a couple things here,” Kliman says. “We need to increase your prenatal surveillance, which might include weekly amniotic fluid checks, biophysical profiles, and even umbilical artery Dopplers. If you feel any more episodes of decreased fetal movement in between visits, or anything that’s unusual, go to labor and delivery immediately and tell them that you are a higher-risk pregnancy, your baby has a small placenta, and there’s a chance of having a stillbirth.”

As one might imagine, the parents like O’Neill who have lost babies to stillbirth (“loss moms,” as they often call themselves) are some of the biggest advocates for integrating this test into the standard of care for pregnant women. In fact, O’Neill is now director of an EPV advocacy group called Measure the Placenta. Together with Samantha Banerjee, executive director of stillbirth prevention organization PUSH for Empowered Pregnancy, she and a small army of loss families have held rallies and completed letter-writing campaigns asking leaders to further investigate and review EPV.

It seems so easy — a noninvasive ultrasound measurement, thrown into the mix of all the other measurements taken during routine scans. It’s a number that will not be an issue in 99% of pregnancies, but could be life-saving for that 1%. So, what’s stopping OB-GYNs from implementing it? This is a question Kliman and mothers like Banerjee and O’Neill desperately want answered. And ultimately, the organization with the influence to transition research into standard clinical practice is the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

[Obstectrics] is one of the disciplines where expectations are highest — a happy young couple enters, planning to leave with a healthy baby — so a loss feels all the more shocking.

ACOG determines the standard of care for expectant mothers, vetting research and distilling all the best evidence into actionable guidance for OB-GYNs to follow. Its current guidelines state that in order to be screened throughout pregnancy for stillbirth risk and eligible for an early delivery (at or before 37 weeks), should your doctor think it will save your baby, you have to have experienced one stillbirth before. For moms like O’Neill and Banerjee, and 21,000 other stillbirth mothers each year, waiting for a baby to die is an absurd hurdle to clear. Banerjee has also lost a child to stillbirth, though not as a result of a small placenta. Over the phone, she shared that her daughter should be 10 years old now.

Kliman, for his part, seems critical of the conservative nature of obstetrics, which is one of the most litigious branches of medicine, according to the American Medical Association. It’s one of the disciplines where expectations are highest — a happy young couple enters, planning to leave with a healthy baby — so a loss feels all the more shocking. “To protect themselves, OBs don’t want to do anything that isn’t totally proven, sanctioned, taught to them,” says Kliman. “So many doctors say, ‘I will do [EPV] when ACOG says I should do it.’” He explains that even if a doctor did EPV measurements for a patient, with the pure intention of offering the best possible care, doing so when EPV isn’t part of the standard of care could open up the provider to being sued.

Banerjee and O’Neill say they have had three separate phone calls with someone who might be able to help: Dr. Christopher M. Zahn, M.D., who is the interim CEO and chief of clinical practice and health equity and quality for ACOG. In the first, they felt he was dismissive, O’Neill says, though he was polite during subsequent meetings. (Zahn denies the assertion that he was dismissive on phone calls with EPV advocacy groups, calling the assertion “offensive.”) Still, O’Neill felt he was trying to direct them elsewhere. “We’ve said, ‘Tell us what level of evidence you’re looking for, and we’ll figure out a way to get it done.’ They don’t seem motivated to create any change, and we honestly don’t understand why,” Banerjee says.

O’Neill and Banerjee say Zahn recommended the loss families come up with some stillbirth prevention recommendations. “And we’re thinking, ‘Wait, isn’t that ACOG’s job?’” O’Neill says. “We have motivated loss families who want to fund research. Parents have pledged to throw tens of thousands of dollars at having a study created that would look at this.” (ACOG says Zahn feels he reiterated the need for standardized and reproducible data. ACOG does not conduct research itself but does advocate for research and its funding.)

Zahn declined an interview with Romper but sent a statement on behalf of ACOG to say that the organization has considered EPV, but research is still needed before it could support a recommendation for universal screening. “Ultimately, there must be high-quality data that establishes the relationship between placental size and potential outcomes independent of other variables and, if a relationship is proven, there must also be evidence of an effective intervention and monitoring approach.”

Actionable evidence would require a randomized trial in which some pregnant patients are screened with EPV and some are not, and then analyzing the outcomes to see if EPV decreased the number of stillbirths, says Jennifer Hutcheon, Ph.D., a perinatal epidemiologist and associate professor in the division of Maternal Fetal Medicine at the University of British Columbia. Because stillbirth doesn’t happen very often, the sample sizes would have to be massive. The main barrier to EPV evaluation, Hutcheon says, is the feasibility of conducting the necessary trial.

Then there’s the question of what it would mean to include EPV in the battery of 3rd trimester tests. There’s a principle in medicine that you don’t screen for something unless you can actually do something with that information. So, if a doctor flags that your placenta is measuring small, how are they supposed to intervene? When you’re trying to prevent stillbirth due to a small placenta, the only solution is delivery, if you’re far enough along for that. “When you’re beyond 37 weeks, and that’s an acceptable time to deliver, it seems to me that even a minor issue like decreased fetal movement and then finding a small placenta, should be sufficient to say, ‘You know what? Let’s just make sure we don’t have a stillbirth tonight and just get this kid out now,’” Kliman says. (He emphasizes that he does not recommend delivering babies any earlier than 37 weeks as a result of EPV findings alone, though an early delivery may be advisable if other markers indicate potential stillbirth.) A thornier question is what to do with tests that show a patient who is less than 37 weeks along has a small placenta; there is no clear recommendation there.

“Some may wonder,” Zahn’s statement continues, “what the harm would be in performing a simple measurement that could potentially provide some insight into preventing stillbirths. However, we have seen firsthand how the over-implementation of technology, such as electronic fetal monitoring, has led to harmful interventions, including potentially unnecessary cesarean delivery.”

Electronic fetal monitoring was first introduced to help prevent fetal asphyxia during birth, which is associated with higher rates of cerebral palsy and death. However, multiple clinical trials have proven that electronic fetal monitoring hasn’t improved those outcomes at all, and it has a high false positive rate, flagging babies who aren’t distressed as exactly that. Randomized trials show that electronic fetal monitoring increases the risk of C-section by 63%. C-sections are common, but they are considerably riskier than vaginal birth for mothers — think higher likelihood of infection, hemorrhage, and even mortality.

Similarly, the existing prenatal screening tools that are considered the gold standard for stillbirth prevention, like measuring a baby’s growth and nonstress tests (NST), aren’t backed by evidence that they are effective. “The tools that we have, like estimated fetal weight charts, perform very poorly and they do not meet the bar for what we would consider an acceptable diagnostic test,” Hutcheon says. Kliman and Hutcheon both point out that nonstress tests, in which the pregnant patient has both their contractions and the baby’s heart rate monitored for 30 minutes, are similarly slim on data supporting their accuracy as a predictor of stillbirth. You might undergo an NST if your pregnancy is high risk, your baby isn’t moving as much as usual, or they’re measuring small.

In a review of trials assessing whether NST actually helps identify infants in distress, Hutcheon says, they offered no improvement in perinatal outcomes. The same goes for the biophysical profile test; a review of trials of that test found no evidence that it improves outcomes, but did increase the C-section rate of those who had it. “So we’re intervening unnecessarily but not improving outcomes,” says Hutcheon. “It’s not only that it’s not accurate, but it could actually be doing harm."

However, once a screening tool is part of the standard of care, it’s nearly impossible to take it back out, Hutcheon explains. If the test is part of routine medical care, which these are, you can’t really research its efficacy anymore because it’s unethical to offer it to some patients while withholding it from others in a study.

“It feels unfair to women to be expected to defend against a risk that they don’t even know exists.”

But with stillbirth rates where they are, it’s fairly obvious OB-GYNs need more tools to prevent it, says Dr. Hayley Miller, M.D., OB-GYN at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health and maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Stanford Medicine. “If we have 30% of stillbirths with unknown etiology, of course we’re missing a tool to help us improve this number,” she says. “I’ve definitely heard of estimated placental volume, and it’s something that I know is in discussion. Currently, we’re not using it as a diagnostic tool to predict small-for-gestational-age or fetal growth-restricted fetuses, but my understanding is it can supplement our understanding on fetuses that are at risk, or that have been diagnosed with fetal growth restriction.”

During my conversation with Miller, she brought up numerous avenues of research into stillbirth prevention she’s aware of, like using baby aspirin during pregnancy for women with hypertension, which increases stillbirth risk. It’s clear that no doctor could be expected to stay abreast of all the promising new tools and techniques in the works for stillbirth prevention, let alone every other facet of perinatal care. To Miller, this is what ACOG’s guidelines are for: sussing out the tests and techniques doctors need right now from all the research in the ether, creating a clear protocol for using them, and making it accessible to doctors everywhere (especially those who aren’t practicing at academic medical centers, where they might hear about these breakthroughs in the break room). So, of course Kliman, O’Neill, and Banerjee need ACOG to back EPV. How else will every OB-GYN know it exists, let alone decide to use it?

Whether or not it believes the current screening tests are effective, ACOG seems to have raised its bar for making changes to the standard of care. There is a human cost to unnecessary medical interventions, which increase the risk of negative outcomes for mothers and babies alike: Early deliveries may land babies in the NICU; mothers healing from potentially complicated preterm inductions or C-sections they may not have otherwise needed. But, as Kliman and O’Neill would point out, there is also a human cost for the system’s inability to change: approximately 58 stillbirths every day in the United States. That’s three kindergarten classes worth of children whose families are forever altered.

With change still a distant possibility, advocacy groups have taken it upon themselves to educate pregnant people about the risk of stillbirth and the prevention tools that might make a difference, if their doctor is willing to try them. Kliman meets virtually with any OB-GYN interested in implementing EPV at no cost to them, reviews ultrasound images and EPV measurements, and helps connect patients who are interested in being monitored this way with doctors who will do it. There are free tutorials for providers available on Yale’s website. Banerjee, O’Neill, and their teams organize awareness campaigns about stillbirth prevention, and recently hand-delivered Kliman’s latest paper to ACOG’s doorstep. O’Neill’s driving force is educating parents about stillbirth and everything they can do to prevent it, so they don’t hear about it for the first time as they’re having one.

“It feels unfair to women to be expected to defend against a risk that they don’t even know exists,” she says. “Our strategy right now is to keep making noise until somebody with authority will see ‘Wow, this is low-hanging fruit to end some preventable suffering.’”

This article was originally published on